Courtesy Catherine Nixon Cooke

Tom Slick Jr. (pointing) on one of his yeti-hunting expeditions in Nepal. In three expeditions, he turned up supposed yeti tracks, yeti hairs, and eyewitnesses, but he never made contact with an actual specimen.

View full image

Courtesy Catherine Nixon Cooke

Tom Slick Jr. (pointing) on one of his yeti-hunting expeditions in Nepal. In three expeditions, he turned up supposed yeti tracks, yeti hairs, and eyewitnesses, but he never made contact with an actual specimen.

View full image

Getty Images /Santiago Urquijo

Is the figure a skier? Or . . . a yeti? You decide.

View full image

Getty Images /Santiago Urquijo

Is the figure a skier? Or . . . a yeti? You decide.

View full image

Courtesy of Catherine Nixon Cooke, from her book “In Search of Tom Slick” (Texas A&M University Press)

Tom Slick Jr., around the time of his Yale graduation in 1938.

View full image

Courtesy of Catherine Nixon Cooke, from her book “In Search of Tom Slick” (Texas A&M University Press)

Tom Slick Jr., around the time of his Yale graduation in 1938.

View full image

Courtesy Catherine Nixon Cooke

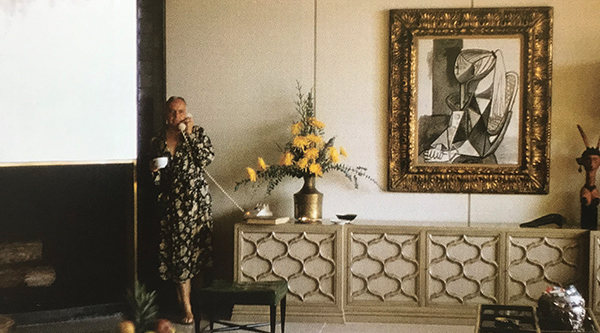

Around 1959, Slick posed for this photo in his O’Neil Ford–designed home in San Antonio, Texas. “He kept a plaster cast of a yeti track on the dining room table,” remembers niece Catherine Nixon Cooke. Picasso’s “Portrait of Sylvette” (1954) is said to have reminded Slick of his daughter.

View full image

Courtesy Catherine Nixon Cooke

Around 1959, Slick posed for this photo in his O’Neil Ford–designed home in San Antonio, Texas. “He kept a plaster cast of a yeti track on the dining room table,” remembers niece Catherine Nixon Cooke. Picasso’s “Portrait of Sylvette” (1954) is said to have reminded Slick of his daughter.

View full image

Courtesy Catherine Nixon Cooke

Slick often traveled by private plane.

View full image

Courtesy Catherine Nixon Cooke

Slick often traveled by private plane.

View full image

If there were a Hall of Fame for Unusual Yale Graduates, Tom Slick Jr. would be among the first inductees.

Junior’s father was Tom Slick, the “King of the Wildcatters” in the Oklahoma oil fields; he died when Tom Jr. was just 14. The younger Slick came to Yale from Oklahoma City. His résumé sounds typical for the immediate pre–World War II era: he managed the Pierson College football team, he was a member of the Political Union, and he graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1938, pre-med.

There was one other thing. In 1937, Slick and a carload of Yale pals loaded his maroon Buick sedan onto the transatlantic ocean liner Bremen, and, as part of a Wandersommer around Europe, traveled to Loch Ness, Scotland, hoping to catch a glimpse of the fabled lake-dwelling monster. There was indeed a famous Nessie sighting in August 1937, according to Loren Coleman, one of Slick’s biographers, “but the Slick group saw nothing.”

The Scotland visit presaged the passion of a lifetime, Coleman explained in an interview. “Tom was very interested in medical mysteries, and he thought if he could capture a hybrid human like the yeti, they might provide some answers to disease prevention or medical research. He had the money to pursue his dream, so he decided to sponsor expeditions in the Himalayas, despite a few frowns and snickers from his family.”

Slick’s interests came to broader attention in a February 1957 New York Times dispatch from New Delhi, headlined “Texan Will Lead ‘Snowman' Hunt.” The story called Slick “a figure in Texas oil and ranching circles” and evinced some skepticism about the three-month-long undertaking, noting that “there are many anthropologists and scientists who believe the whole story of the creature of the rocks is a myth, that the abominable snowman has the same relation to zoology as has the unicorn.”

Although the quest for the abominable snowman, or ABSM in explorers’ shorthand, now seems like a quixotic adventure, looking for an unknown Himalayan hominid didn’t seem so outlandish in the 1950s. Renowned British mountaineers, such as Eric Shipton and John Hunt, leader of the successful 1953 conquest of Everest, had seen mysterious footprints in the Himalayas. Sherpa Tenzing Norgay, who summited Everest with Edmund Hillary, claimed to have seen a yeti, not an unusual report among the Himalayan mountain people.

Furthermore, some once-legendary animals of the remote Indian-Nepalese-Tibetan highlands did in fact exist in reality. The giant panda, for one, had enjoyed a quasi-mythological existence before the twentieth century arrived. So, back in the 1950s, searching out another giant hypothetical Himalayan creature didn’t seem like such a stretch.

In 1957, Slick led a famous yeti “reconnaissance.” They interviewed eyewitnesses and found supposed yeti tracks and yeti hairs, but they had no direct contact. Slick bankrolled two other yeti quests; in one, he outfitted the expedition with three female bluetick hounds, known for their superb tracking skills. In another startling incident, members of a Slick-financed expedition allegedly stole a thumb and phalanx bone from a purported yeti hand kept at Nepal’s Pangboche monastery. (It’s said the thieves were wary of a thorough search by customs officials, so they convinced a friend—the actor Jimmy Stewart—to take the stolen body parts out of the country.) Authentication of the “Pangboche hand” proved problematic, as with so many ABSM-related ventures.

Slick lent his efforts and his dollars to other cryptozoological treasure hunts. In his book Tom Slick and the Search for the Yeti, Coleman describes Slick and associates “pouring money into the Bigfoot hunt in the United States.” Slick likewise sought out the storied “giant salamanders” of Northern California’s Trinity Alps. Slick’s niece Catherine Nixon Cooke, author of In Search of Tom Slick: Explorer and Visionary, remembers her uncle as a friendly and engaging raconteur eager to share stories of his exotic travels. “He kept a plaster cast of a yeti track on the dining room table, and we’d have dinner and we would talk about it,” she recalls. “Children loved being around him.”

Slick was the proverbial man of many parts. Now a small-bore internet sensation because of his yeti-hunting, he was also an author, a citizen diplomat, an art collector, and an important philanthropist whose creations have survived his premature death in a 1962 plane crash at age 46. Case in point: in San Antonio, Texas, Slick founded the Southwest Research Institute, an independent 3,000-person nonprofit that does research in engineering and physical sciences ranging from oil and gas exploration to deep-space missions. He also created the Texas Biomedical Research Institute, whose 350 employees conduct infectious-disease research, and the Mind Science Foundation (MSF), which describes its mission as an exploration of “the puzzle of human consciousness.”

Cooke, a former chief executive of the MSF, says Slick’s unusual Himalayan experiences kick-started his inquiries into the paranormal. “He saw lamas levitating, and people turn water into ice. He wanted to know if there was any science behind that,” she explains. And, she points out, “some of the things that interested him in the 1950s have now entered mainstream medicine—for instance, biofeedback, mind-body health, and the positive impact of meditation on health.

As if that weren’t enough, Slick also wrote two books on international affairs—The Last Great Hope, about the United Nations, and Permanent Peace: A Check and Balance Plan—and endowed a chair of international affairs at the University of Texas. In addition, he accumulated an extraordinary art collection, portions of which his family has donated to the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio. A 2009 exhibit of those donations included works by Pablo Picasso, Raoul Dufy, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Larry Rivers.

Perhaps inevitably, Hollywood came calling. A 1997 Variety article reported that Nicolas Cage was to star in a dramatic comedy titled Tom Slick: Monster Hunter: “Story is a comedic action escapade about an oil tycoon who spends his family fortune on a global quest to track down the world’s legendary monsters, including the Loch Ness Monster, Yeti, etc.” The project went nowhere, but Coleman says another director is developing a more serious film about Slick’s adventures.

In researching his biography on Tom Slick, author Coleman corresponded with Hillary, who became an ABSM skeptic after leading the 1960 Himalayan Scientific and Mountaineering Expedition. “I met Tom Slick only on one occasion,” Hillary wrote to Coleman. “It was quite clear he was very much convinced of the existence of the Yeti. . . . He seemed determined to carry on the search until a firm conclusion had been reached. If it hadn’t been for his premature death then he might still be looking.”

loading

loading

1 comment

-

111, 8:38am March 08 2021 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.笑死