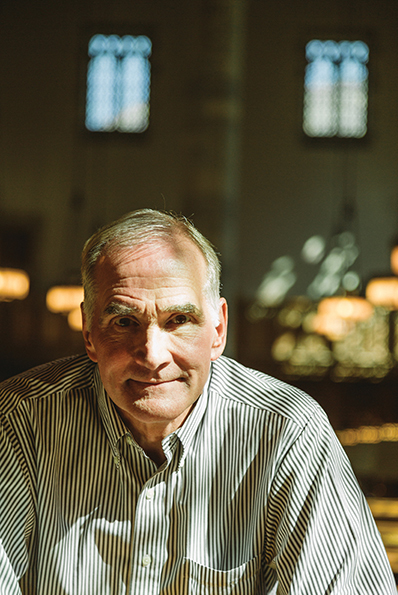

Portrait by Driely Vieira

David Swensen ’80PhD ran Yale’s endowment for 35 years and revolutionized institutional investing.

View full image

Portrait by Driely Vieira

David Swensen ’80PhD ran Yale’s endowment for 35 years and revolutionized institutional investing.

View full image

Driely Vieira

Dean Takahashi ’80, ’83MPPM (right), worked alongside Swensen in the investments office for 33 years.

View full image

Driely Vieira

Dean Takahashi ’80, ’83MPPM (right), worked alongside Swensen in the investments office for 33 years.

View full image

Driely Vieira

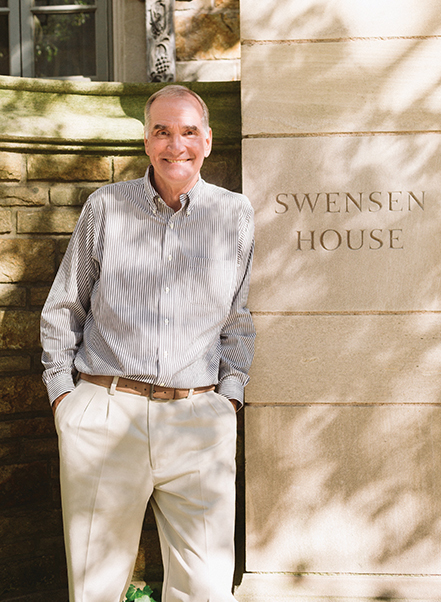

Swensen was a freshman counselor and later a fellow of Berkeley College, which named its Head of College house Swensen House in his honor in 2013.

View full image

Driely Vieira

Swensen was a freshman counselor and later a fellow of Berkeley College, which named its Head of College house Swensen House in his honor in 2013.

View full image

When David Swensen ’80PhD died on May 5 after a nine-year battle with kidney cancer, he was remembered throughout the financial world for his Midas touch. Over his 35-year tenure as chief investment officer at Yale, Yale’s endowment averaged a remarkable 13.1 percent return, adding billions of dollars more to the university’s coffers than a conventional investment strategy would have. His strategy of looking beyond publicly traded securities to private equity and illiquid assets changed the way institutions invest—not least because so many of his former employees were hired to run other institutions’ endowments. As of June 30, 2020, the endowment was worth $31.2 billion and funded more than a third of Yale’s budget.

As many money people observed, he could have made a fortune running a hedge fund instead of taking a university salary. The fact that he didn’t said a lot about what made him tick. Swensen, born in Iowa in 1954 and raised in Wisconsin, was the son of a college professor, and he grew up steeped in the idealism of the state’s progressive and public-minded politics. After graduating from the University of Wisconsin at River Falls, he came to Yale for his doctorate in economics. He studied with Yale’s Nobel Prize–winning economist James Tobin, who was one of the architects of the portfolio diversification strategy that Swensen would employ when he returned, in 1985, to run Yale’s flagging endowment. He stayed at the university for the rest of his life, raising three children who survive him, as does his wife, former Yale women’s tennis coach Meghan McMahon ’87. (He and his first wife, Susan Foster, divorced.)

Swensen was mostly lauded during his career at Yale, but he took his share of criticism from activists who wanted Yale to divest from certain industries or be more transparent about its holdings. He used the bully pulpit of his fame in the investing world sparingly but effectively: he urged individual investors to put their money in simple index funds and avoid riskier and costlier options; he declined to invest in companies that sold assault weapons; and last fall, he announced that his office would monitor the diversity of personnel in Yale’s outside asset managers.

If David Swensen had been the kind of investment manager who holed up in his office with a green eyeshade, poring over numbers, Yale surely couldn’t have complained, given his results. But one of the reasons he was at Yale instead of on Wall Street is that he deeply loved the university and being part of its community. The tributes that follow will tell you a little bit about his work managing the endowment, but you’ll learn a lot more about him as an enthusiastic and essential citizen of Yale. He has been honored at Yale with an honorary doctorate (in 2014), the renaming of the Berkeley Head of College house as Swensen House, and the naming of the tower of the Humanities Quadrangle (formerly the Hall of Graduate Studies) as Swensen Tower. But even without those memorials, David Swensen would be impossible to forget.—The Editors.

Serving Yale’s mission

By Peter Salovey ’86PhD

Pragmatic and visionary, analytical and compassionate, David Swensen saw the world as it was; then he made it better. Over the course of his remarkable career, he transformed the way Yale managed its endowment—and in doing so completely changed the field of institutional investing, vastly augmenting the financial resources available to our university and, indeed, much of higher education. But this is only one piece of what he did for Yale and for others.

For David, his work with the endowment—critically important as it was—always served a larger purpose: Yale’s mission in the world. David believed deeply in this mission and in the promise of light and truth. He believed that opening Yale’s doors wider to the most talented and deserving students would ripple beyond our campus, improving every sector of society. He believed in the power of research and ideas to help us find meaning and extend life. Through his brilliant stewardship of Yale’s resources, David helped us fulfill our responsibilities to the world, while leaving an enduring imprint on this university. His work was quiet and largely unseen by many, but we—students, faculty, staff, and alumni—are its daily beneficiaries.

No one could have been happier to do this for Yale. What mattered to David—what filled his soul—was being part of the Yale community. He loved his colleagues in the investments office, the Berkeley College fellowship, and the Department of Economics and the many faculty members he revered there. He loved New Haven, Yale’s home city, and he loved Yale athletics and the arts. The stands at football, hockey, and basketball will seem empty—and certainly quieter—without him.

And David loved a party: office events; reunion weekends with alumni from across generations; beer tastings for seniors in the residential colleges; the Blue Leadership Ball; tailgates before football games; the tennis and golf tournaments he hosted. He reveled in commencement—Yale’s largest and grandest celebration—and the way it brought so many together. This year, writing this as I prepare for commencement, I can picture David on the platform, looking out onto the sea of graduates. He took so much pride in Yale’s students—the ones he personally mentored and the many more he helped through his work.

One year at his birthday party, his wife Meghan introduced the singing of a song that was very special to David: “The Impossible Dream,” composed by Mitch Leigh ’52MusM. There were tears in David’s eyes as an undergraduate tenor sang, “To dream the impossible dream / To fight the unbeatable foe . . . To try when your arms are too weary / To reach the unreachable star.”

David did live his own impossible dream—and in doing so, he made all of Yale’s dreams more possible. This is what I will remember of my friend David Swensen, an extraordinary and beloved citizen of Yale, and this is his legacy.

Peter Salovey ’86PhD is the Chris Argyris

Professor of Psychology and president of Yale.

The secret of his success

By Richard Levin ’74PhD

Jock Reynolds, the longtime director of the Yale University Art Gallery, told me a story that sums up the motivation for David Swensen’s brilliant work. Attending his first commencement, Jock found himself seated on the platform next to David. Trumpets sounded, banners unfurled, and students bearing the flags of all the schools and residential colleges began their march from the rear up the center aisle, with their classmates following. Looking out at the grand spectacle, David leaned over to Jock and said: “Here come the returns on our investment.”

David Swensen revolutionized the field of institutional investment management; his influence is felt around the world. Although his contributions to fund management practice are well-known and widely recognized, his genius is not fully understood. Yes, he shifted endowments toward illiquid investments, invented new asset classes, and developed rigorous methods for allocating funds across these classes, optimizing the spending rule, and rebalancing the portfolio. And, yes, all this analytical rigor produced demonstrably superior endowment performance early in David’s career at Yale.

But a mystery remains. By the late 1990s most of Yale’s peer institutions had adopted David’s methods and diversified their portfolios. Yet for years thereafter, Yale continued to outperform its peers. This mystery is resolved by recognizing that at the very heart of David’s genius was not his analytical rigor; it was his extraordinary judgment about people.

His judgment manifested itself, first, at home. David had an eye for talent. Fifteen members of his investments office team moved on to lead endowments at major foundations, colleges, and universities—including Princeton, MIT, Stanford, Penn, Bowdoin, Wesleyan, and Smith. The long-term “holds” of his first generation—Dean Takahashi ’80, ’83MPPM, Tim Sullivan ’86, and Alan Forman—could have moved anywhere in the investment world, with larger rewards and higher rank, but their loyalty to Yale and David kept them here, to our great good fortune.

It wasn’t only talent that David sought; it was also character. David set the highest standard of honesty, transparency, and ethical behavior for himself, and he expected this of not only our staff, but also of each of the 100 to 150 investment partners to whom we allocated capital. He achieved this standard by training his staff to undertake thorough due diligence, not simply analyzing the investment performance of prospective partners, but securing in-depth references from virtually every potentially knowledgeable source.

One of our most talented investment partners, Nancy Zimmerman of Bracebridge Capital, is fond of a metaphor derived from tennis: “You can’t chase every ball.” As David’s longtime doubles partner, I can attest that he did chase every ball, and not only on the tennis court. He tracked down and puzzled out every bit of evidence on the character of our managers: How did they run their organizations? Did they share credit and rewards generously with their teams? Did they treat their investors fairly? Did they cut corners in making decisions? Were they scrupulously honest? David invested only with partners whose integrity he admired.

It was a winning strategy. Relative to our peers after the late 1990s, the largest fraction of Yale’s excess returns derived from better manager selection within asset classes; much less came from having a better allocation of funds across asset classes.

The superior performance of the endowment made possible all that Yale has accomplished in the past 30 years: the rebuilding of the campus, the rejuvenation of downtown New Haven, the internationalization of our student body and academic programs, our commitment to making Yale College affordable for all who are admitted, and our investments in world-class science and engineering. David made my job easy. He was my friend for 45 years; he called me “boss” for 20, and we were kindred spirits throughout. For me, for Yale, and for those whose lives he touched, he is irreplaceable.

Richard Levin ’74PhD, the Frederick William Beinecke Professor of Economics, Emeritus, was president of Yale from 1993 to 2013.

A remarkable generosity

By Dean Takahashi ’80, ’83MPPM

David Swensen is well recognized for his extraordinary contributions to finance and endowment management, but his generosity reached far and wide. As a close friend and colleague for 45 years, I was fortunate to witness his kindness in caring for and supporting his family, friends, and partners. His trust and encouragement led those around him to do their very best, and he relished their success.

I was incredibly lucky to have David Swensen as freshman counselor when I arrived at Yale in the fall of 1976. We quickly became friends and had fun playing all sorts of games, eating pizza, and hanging out in Berkeley College. Over the years, whether it was bridge, softball, tennis, or investing, Dave often proclaimed he always wanted to be on the same team as me. The feeling was mutual. Dave loved to compete and excel, and I tried my hardest to be worthy of his expectations and trust.

Over the many years of friendship and working for Dave, I was awed and inspired by many of the kind deeds that weren’t featured in the national press. He befriended and cared for folks from all walks of life around Yale and New Haven. He knew everyone at his favorite haunts, like Mory’s and Yorkside Pizza, and insisted on treating his guests. David wrote his book, Unconventional Success, to protect the individual investor from Wall Street avarice. I’d see him spend countless hours sitting down one-on-one with friends counseling them on their finances and investments. He volunteered many hours each week to coach neighborhood kids in baseball and soccer. Often, he would make special trips to pick up or drop off players who didn’t have rides to practice or games.

He was incredibly selfless and generous in befriending and helping Yale students. Two days before he died, I asked him how he was doing. He wrote, “I’m doing OK—My infection is worse, but I am good to go for class.” He went on to lead a discussion on the new “Yale Investment Office: November 2020” case study for our senior economics seminar, Investment Analysis.

It is so fitting that the case study opens with Dave reminiscing about how honored and lucky he was to conduct the official coin toss for “The Game” between Yale and Harvard in the fall of 2019. He had met and befriended many of the Yale football players, inspiring them with his passion and faith in their effort. Despite his ongoing battles with cancer, Dave and Meghan hosted a broad collection of friends and doggedly cheered on the team through the protests, the double overtime, the thinning crowds, and the oncoming darkness. Dave was overcome with tears of joy when Yale finally won the greatest of all The Games.

David loved to see his friends succeed. He was a hero near and far in ways big and small.

Dean Takahashi ’80, ’83MPPM, is executive director of the Yale Carbon Containment Lab. He worked alongside David Swensen at the investments office from 1986 to 2019.

An intern’s view

By Georgianne Valli-Harwood ’87

I met Dave Swensen when he first arrived to manage Yale’s endowment; I was the first intern in that office. It was a cramped upper-floor space with old carpet and pushed-together desks. He moved in and was very excited about his new “partner’s desk.” I don’t remember how I landed that internship, but I do remember being immediately swept up in his tremendous energy. He was brimming with ideas about how to invigorate the management of the portfolio, and he was eager to get started.

He took me—a completely uninitiated junior with no background or education in money management—to his first meetings with Yale’s traditional portfolio managers. In these meetings he pleasantly but unequivocally told fund manager after fund manager that underperformance was no longer acceptable and more was expected. He was young at that time, but absolutely self-assured. It was a remarkable education, just witnessing how he handled these reviews.

I learned more in that internship about managing investments and money than I did in the decade I later spent in investment banking, lessons I use now only to manage my 401k. I left finance for medicine because I just wasn’t as interested in money as I was in people. But in retrospect, I internalized more important lessons from witnessing a man with a mission, a goal, and the confidence and diplomacy to make it happen. That mentoring has served me well in my medical career interacting with patients, colleagues, and administrators, and has even helped me be a better family member. Thank you, David!

Georgianne Valli-Harwood ’87 is a cardiologist in Massachusetts.

The team

By Anne Martin

I met David when my kids were assigned to his team during Little League signup right after we moved to New Haven. When Dave discovered my husband was the new rowing coach at Yale, he became a lot more interested in finding ways to help us get settled in the community, including giving me a job!

I was an unusual hire in the office. David loved hiring young people and training them. I was older (42), but I had many of the ingredients David looked for: a good academic pedigree, a competitive nature (I was on the national rowing team for several years after college), and I was enough of a blank slate that David saw me as good raw material. I stayed for six years before taking the CIO job at Wesleyan (with his strong support).

I got to know David as a coach, but it turned out he was much the same in the office. David brought a coach’s patience to the job along with his ability to explain and encourage. Yes, like most coaches, he could go ballistic, especially if he saw an instance of bad sportsmanship, but like the best coaches, he recognized talent and was willing to wait years for people to reach their full potential. By pushing down responsibility early and setting expectations high, he developed a team of very capable investors.

One of the most meaningful aspects of the culture David created was the shared credit for the wins and the lack of blame for losses. Coming from investment banking, this was hugely eye-opening for me. There was never any finger-pointing. David was forward looking. You could never change the past, only make better decisions going forward. Decisions were made by the team and accountable to the team.

Another eye-opener was David’s approach to investing. Of course, as a PhD in economics, Dave was intensely analytical. Endowment risk was modeled and re-modeled. But what really made him special was his ability to read people. Manager selection was at the root of Yale’s success and like any good coach, David was good at figuring out which managers would be a fit with the values and ethics of the team he had put in place for Yale.

Anne Martin has been chief investment officer at Wesleyan University since 2010.

Disagreeing—and discussing

By Kahlil Greene ’22

When I was finance director of the Yale College Council, I worked with Mr. Swensen to produce a six-minute YouTube video to clarify how the endowment is managed. At the time, he urged me to call him Dave, which was indicative of his desire to be familiar and friendly with students.

Following the completion of the project, Dave invited a member of the YCC business team and me to Mory’s. It was my first time at Mory’s, but I remember Dave giving us a tour with a detailed history of the building and the traditions that took place there. At one point, Tony Reno, the coach of the Yale football team, came up to our table to say hello; he ended up educating my teammate and me about the impact of Dave’s work in the investments office. Dave held a warm smile, but as an extremely humble man, he rarely shared his accomplishments himself. And so, that was the first time I truly understood the legacy he would leave.

Later on, I found myself ideologically at odds with Dave when I became student body president and advocated on behalf of students calling for Yale to divest from fossil fuels and cancel its holdings of Puerto Rican debt. The Yale College Council Senate unanimously voted to support these demands in early 2020. Soon after, Dave invited me to his office to explain why he disagreed with the demands.

I found key differences between his viewpoints and those of a large portion of the student body that were difficult to reconcile. But these discussions would not have been possible without Dave holding on to one of his core drivers—wanting to support and connect with Yale students. This was one of his most prominent qualities, and it shone through in every interaction I had with him, regardless of the topic of discussion. I am very grateful that I had the opportunity to meet him, and I will remember his intelligence, openness, and kindness above all else.

Kahlil Greene ’22, the first Black president of the Yale College Council, is a senior in Timothy Dwight College.

Beer and wine in Berkeley

By Marvin Chun

In the “society of friends” that is Yale, privileged are those who knew David Swensen. Over my nine years as master of Berkeley College, which as a fellow, David would describe as “the best college,” I tapped hundreds of Berkeley seniors into the Swensen Society, the name engraved onto glasses that I gave them to keep as a memento from his legendary beer and wine tastings.

Since the days of former master Robin Winks in the 1970s, when David had served as a freshman counselor, he led one of the college’s greatest traditions—beer tastings. Apparently started as a prank by David and his mentees, including his longtime investments office partner Dean Takahashi ’80, ’83MPPM, the Berkeley Beer Tasting evolved into a theatrical production that featured over a dozen lagers, ales, and stouts from around the world, ending with dessert-like lambic beers.

Picture the neatly displayed bottles on a table awaiting students in the elegant living room of the Berkeley Head of College House (now called Swensen House).

Throughout the evening, David would carefully describe the brewing differences and histories behind each beer, with long pauses between each to encourage drink and conversation. His teaching enthusiasm and expertise were matched only by his son, Alex, who, with a strong command of American microbrews, co-led the beer tastings with his father.

My contribution to this tradition was to ask David to add wine tastings, and he eagerly did so in 2008. David was so excited to share his passion that he brought multiple cases of wine, sampling the amazing range that oenophiles spend a lifetime exploring. He taught students how the same grape can produce such different flavor profiles, he challenged students to discern the differences between Old World and New World wines, and he encouraged them to come up with poetic descriptions of each one. David would share special wines from his own collection; I remember several as the best I’ve ever tried in my life and may never taste again.

Our inaugural wine tasting was epic, and it lasted over five hours past midnight, when we realized that most of the students couldn’t keep up and had quietly retired for the evening. Since then, as yet another sign of David’s generosity, he split the wine tastings into separate white and red wine tastings, giving three evenings of his time to Berkeley seniors every year, which my successor, Head David Evans ’92, also a Berkeley alumnus, fully supported up to the pandemic.

The beer and wine tastings were lively seminars for learning and conversation. Three additional Berkeley alumni helped make them multigenerational: Meghan McMahon ’87, David’s wife; Dean Takahashi; and Wendy Sharp ’82, Dean’s wife. Although Berkeley was privileged to have three events a year, David would offer a tasting event to any college that requested it.

These are traditions that need to continue, and when I host tastings in David’s memory, I look forward to sharing an introduction that I read at my final wine tasting with him in 2017, describing at length how much I admire his contributions to Yale, and his generous, fun, and resilient spirit. Toward the end of that introduction are these words: “His overflowing love for life and for those around him is what makes him Yale’s biggest asset. He radiates love and joy in everything he does.”

Marvin Chun is dean of Yale College and the Richard M. Colgate Professor of Psychology and Professor of Neuroscience.

Coach Dave

By Mark Alden Branch ’86

The world knew David Swensen as a genius who made billions of dollars for Yale and changed the whole field of institutional investing. But our family knew him first as Coach Dave. When my son John entered youth soccer at age five, Dave ran the clinic for the youngest players. He was unfailingly positive and kind with the kids, and he always worked to draw the best out of them as athletes and people.

Dave moved up the age levels as a coach along with his younger son Tim, and because Tim and John were the same age, John got to have Dave as a coach almost every year he played soccer. (And Dean Takahashi ’80, ’83MPPM, was his partner in coaching just as in the investments office; Dean’s son Kai was in the same cohort.) Dave continued to teach them well as their skill level and maturity increased, expecting more of them—and getting it.

In John’s first year of soccer, there was an article on the front of the New York Times business section about university endowments with a huge picture of Dave. On seeing it and hearing my explanation of why he was in the newspaper, John said, “I didn’t know Coach Dave had another job!”

Dave liked to tell that story; I think he told it to at least one journalist who was writing about him. On one level, it’s just a cute story about how kids don’t think of adults outside the context in which they know them. But I also think Dave liked the idea that when he was coaching, nobody could imagine that he had anything else in the world to do. I suspect that the same was true in all of his pursuits.

Mark Alden Branch ’86 is executive editor of the Yale Alumni Magazine.

A born competitor

By Penelope Laurans

Among my favorite memories of David is his leadership of the Investments softball team called the Stock Jocks. In the nineties, every summer the Stock Jocks played Rick Levin’s team from the president’s office, which was named “Rick’s Rookies.” You may think this was for fun. And it was, on the surface. After the game everyone repaired to the president’s house for pizza and good cheer. But it pitted two of the most competitive people in the universe against one another: David Swensen and Rick Levin. And they both wanted to win. Badly. Even at softball. The dessert after the game always consisted of two ice cream cakes from Ashley’s—one inscribed “the thrill of victory,” the other “the agony of defeat.”

Let’s just say that the investments office team, with its youth and vigor, had it over the president’s office by quite a lot. However, Rick’s Rookies had one secret weapon: athletic director Tom Beckett, who would simply stand there with the bat over his shoulder like a sack—and every time he was up reach out and smash a homer. Swensen tried everything to get him off the president’s team. Once he alleged “no former professional players allowed.” (Beckett had once played pro ball.) Then he said that only direct reports could play and queried whether Beckett was actually a direct report to the president. (He was.)

The competition between the teams ended when Levin tore his hamstring stretching for a ball at first base and Swensen twisted his ankle and was on crutches from another game, and it was decided that Yale needed a president and investment manager more than two softball players. But the measure of Swensen on the field of play—where he always left it all—was that he never gave in. Ever. As Churchill put it, “Never give in. Never, never, never, never. . . . Never yield to force; never yield to the apparent overwhelming might of the enemy.” He brought that attitude to bear in everything, including his battle with cancer. He married that passion with vision, daring, generosity, integrity, fierce loyalty, partnership, devotion to education, and belief in an enterprise larger than himself, a model for every student in his classes, every member of his office—and for us all.

Penelope Laurans is a senior adviser at the university. She was head of Jonathan Edwards College from 2009 to 2016.

loading

loading