Beinecke Library

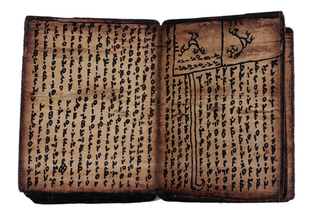

Made by the Batak people of northern Sumatra between 1860 and 1920, this pustaha offers descriptions of rituals, specifically the use of birds for divination.

View full image

In the twenty-first century, we in the wealthier nations are quite accustomed to books on paper. Even with the rise of digital reading platforms, many of us still have overflowing bookshelves. Leather-bound or paperback, a book you crack open will likely present you with orderly rows of neat, printed text on creamy white paper. Of course, this familiar and fond experience is not universal. Many different cultures have made books in all sorts of forms, from scroll to codex, and out of a kaleidoscope of materials, from parchment to bamboo.

The image shown here, of a bark book in the Beinecke Library’s collection made by the Batak people of northern Sumatra, challenges our notion of what a book is. This particular volume is a divination book, also called a pustaha, which was made for use by a datu: a shaman and healer. Pustaha are frequently made of materials like the bark of an Aquilaria tree, a writing surface unique to the Batak people.

While pustaha deal with medicine or divination and are the dominant type of surviving book from pre- or early colonial Batak society, other objects preserve other traditions, of love laments and poems. These books entered the realm of Western scholarly interest in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in part driven by their perceived exoticism and by the intervention of German missionary and Dutch colonial interests in Indonesia.

A pustaha could be used as an informal (and highly individual) way of recording instructions for how to complete a particular rite. Such a document could support oral instruction for the beginning datu and serve as a reference work for the well practiced. The Yale book, like most pustaha, is folded like an accordion—a style of binding that has found popularity in manuscript cultures around the world. It is made of a single, thin, long strip of bark.

Dated to between 1860 and 1920, this example is written in Hata Poda, a language that was long thought to be understood only by the datu himself. The writing was carried out by use of a sugar palm pen dipped in a specially prepared black ink. Batak, as a language group, is divided into six subcategories, representing the diversity to be found between northern and southern ethnic groups of Batak people. As a result, surviving pustaha can act as witnesses to the linguistic differences among the Batak peoples.

Divination practices vary widely from place to place: from casting sticks to observing astronomical phenomena to reading tarot cards. The rituals in the Beinecke pustaha fall into the category of augury, in this case the use of birds for divination. Used by cultures around the world, augury often demands the dissection and examination of a bird’s entrails for hints about what is yet to come. As beings that exist between the heavens and the earth, birds were thought to communicate instructions from gods and foretell future events. Their entrails became ciphers to be read by the datu on behalf of his followers.

In the upper right corner of the pustaha, one can see two illustrations of birds that resemble chickens, complete with jaunty combs. These charming illustrations are just two of the 45 images of men and birds to be found throughout the manuscript.

loading

loading