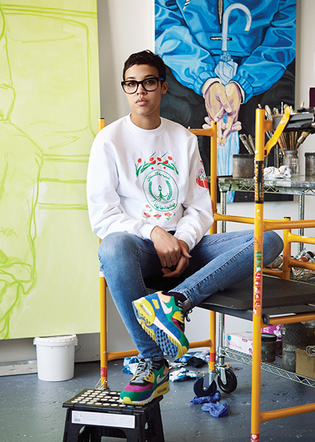

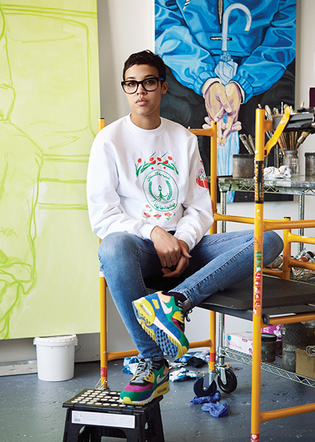

David Schulze. Courtesy of the artist.

Every painting has a different story to tell,” says artist Jordan Casteel ’14MFA—whether it’s about a garden, Harlem at night, or a hard-working woman selling hats.

View full image

At her first New York solo show, in the year she graduated from art school, Jordan Casteel ’14MFA presented a series of startling portraits. The subjects were former Yale classmates, all of them Black men. Drawn from tradition but defying expectations, the lushly painted figures are intimate and vulnerable, gazing at the viewer from their living rooms and bedrooms. The title was Visible Man. Since then, Casteel has gained critical acclaim for her expressive, empathetic portraits of people of color. Her luminous paintings have been featured in gallery and museum exhibitions, and on the covers of Time and Vogue. Last year, when she was awarded a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship, the foundation recognized the power of her artwork to connect people beyond the canvas and the gallery: “Casteel prompts viewers to meet the gaze of others and to recognize our shared humanity.”

Robin Cembalest: Congratulations on the MacArthur! What did it feel like?

Jordan Casteel: It’s one of the most humbling experiences I ever had in my life! I can’t believe that it’s real, but it very much is.

RC: The foundation cited your experimental paint handling, the multicolored skin tones that invite viewers to consider “Blackness” as concept and social construct. And there’s that intimacy, the domestic settings, that powerful gaze.

JC: I think a lot about who’s going to experience this work. I want people to feel a certain amount of connection and empathy. Every painting has a different story to tell, but I also love when people are finding other things and experiencing it in their ways because that’s always going to happen—especially when you are referencing people, even if they are real people in the world, as they are. There are certain implications or experiences other people are placing on them, memories or familiarity, whether it’s recognizing the jacket somebody’s wearing and it reminds them of their grandmother, or whatever it might be that trails through their own personal life experience.

RC: Featuring people in your own life is an essential part of your process. For your 2017 series Nights in Harlem, you painted subjects you encountered in and around the Studio Museum in Harlem during your artist residency. You met Fallou, who designed hats and sold hats on the street. You painted her with her brother, visiting from Senegal, in the double portrait The Baayfalls. Now it’s a public artwork—reproduced on a building adjacent to the High Line at 22nd Street in New York City, through this spring.

JC: When they reached out, it was clear that this was the painting that needed to be represented. It embodies New York at its core; it’s a young immigrant woman who is hustling to get her own career off the ground. And she’s doing it. You see the street, you see the community, you see her own creativity, the energy of her and her brother, the colors.

RC: Your work is part of Black American Portraits, a two-century survey timed to coincide with the Obama portraits show at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art [through April 17]. The piece is something of a departure for you: it’s a self-portrait.

JC: It was representative of 2020, a time of real isolation, when turning inward was paramount for many. We had no choice but to think about self. My practice has been so centered on externalizing self, moving outside myself into the lives of others—though there are reflections of who I am. To do a self-portrait was an opportunity for me to think, Okay, if I’m so interested in projecting outward, what happens if I begin to project inward? It’s pretty profound to have it on public view.

RC: In your recent show at London’s MassimoDeCarlo gallery, you revisited another artistic genre: landscape. In Nasturtium, a portrait of your garden, you lavish each leaf and tendril in your garden with the meticulous care you bring to human forms.

JC: I was petrified to make that painting because I didn’t understand where it fit in the story I had been telling as a whole. But once I made it, it proved to offer a lot of opportunities for me to jump off of.

RC: What are your future plans?

JC: Every time I’ve taken a risk within the painting practice, exciting things come from it. I’m trying to lean into fearlessness.

loading

loading