Yale University Art Gallery

This box, some 3¼ inches wide, was presented by the City of New York in 1784 to Baron von Steuben, in honor of his exceptional service in the Revolutionary War.

View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

This box, some 3¼ inches wide, was presented by the City of New York in 1784 to Baron von Steuben, in honor of his exceptional service in the Revolutionary War.

View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

Yale University Art Gallery

Yale University Art Gallery

Yale University Art Gallery

In the collection of the Yale University Art Gallery is an oval box made of solid gold and decorated with elaborate engraving. At just over three inches wide, it fits easily into the palm of an adult’s hand. Though small in scale, this gold box has an outsized significance in the history of American metalwork and in the history of the nation itself. It was commissioned by the Common Council of the City of New York for Major General Friedrich Wilhelm Augustus, Baron von Steuben, in recognition of his role in the Continental army during the Revolutionary War.

The custom of granting the freedom of a city originated in medieval Europe as a way of honoring dignitaries and military heroes. The honor was sometimes paired with the physical gift of keys or a gold box. (The tradition of presenting the keys to a city as a mark of honor continues today.) Local papers recorded such presentations across Europe.

In September of 1784, the Common Council proposed that five individuals be “presented with the freedom of this City in Gold Boxes.” These so-called “freedom boxes” were rarely made in the North American colonies; thus, the Common Council’s decision to present its own freedom boxes was unusual, and bold. They selected New York governor George Clinton, General George Washington, John Jay, the Marquis de Lafayette, and von Steuben. Each received a letter of commendation; only von Steuben and Jay are known to have received boxes.

(Jay’s box is now a promised gift to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.)

The silversmith Samuel Johnson served on the Common Council and was appointed to the committee charged with having the boxes made. Both surviving examples bear Johnson’s mark, suggesting that he gave the commission to himself. The elaborate decoration, however, was the work of the specialist craftsman Peter Rushton Maverick, who trained as a silversmith before becoming an engraver of copper plates for prints and paper currency. Maverick filled the lid of the box with an elaborate version of the seal of the City of New York, which depicts an Anglo-Dutch trader and a Native American flanking a shield displaying beavers and barrels between the sails of a windmill. This iteration of the seal had been adopted earlier in 1784, making the box an up-to-date record of the city’s visual identity.

The dedicatory inscription encircles the box and reads: “Presented by the Corporation of the City of New York with the Freedom of the City.” Around the edge of the lid and on the sides of the box, Maverick added shimmering bands of flowers and swags, formed by broad, shallow gouges of his engraving tool. This method is called “bright cut” engraving, and these boxes are the earliest dated appearance of this technique in American metalwork. Maverick prominently signed the lower edge of the lid, announcing his pride in his work.

Baron von Steuben, born in Prussia, had joined the Prussian army when he was 17. He fought in Europe in the Seven Years War, and later served the Prince of Hollenzollern-Hechingen, who gave him the title of Baron. After meeting Benjamin Franklin in Paris, von Steuben joined the Continental army in 1777. He introduced sanitation standards and rigorous training techniques that improved the quality of army life, and he eventually became Major General and a confidant of George Washington’s. After the war, he set up house in New York with his former aide-de-camp, William North, and campaigned for the rights of immigrants; he also helped found the Society of the Cincinnati, the oldest patriotic organization in the United States.

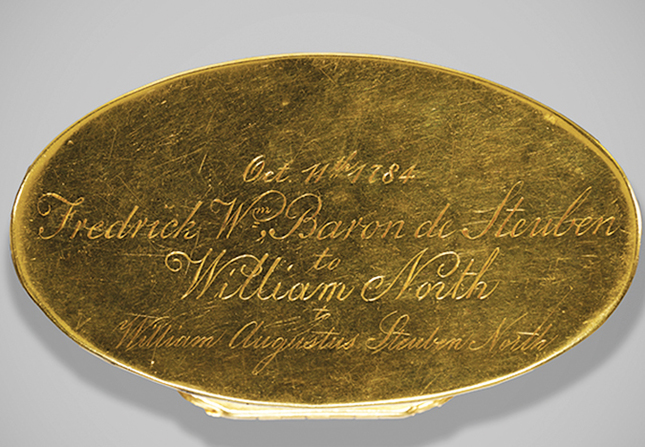

Baron von Steuben died in 1794, a decade after receiving his box. He clearly treasured it, and he made careful provision for it in his will: “Sufficient reasons having determined me to exclude my relatives in Europe from any participation in my estate in America, and to adopt my friends and former aides-de-camp, Benjamin Walker and William North as my children, . . . [to] the said William North I bequeath my silver-hilted sword, and the gold box given me by the city of New York.”

The sword and box, together with a portrait of von Steuben, remained in North’s family until 1929, when they were put up for auction. Francis P. Garvan, Yale Class of 1897, bought the box and sword and donated them to Yale as part of the Mabel Brady Garvan Collection. Yale acquired the portrait in 1939. All three works are reunited in the exhibition Gold in America: Artistry, Memory, Power, now on view at the Yale University Art Gallery.

loading

loading