Courtesy Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History

Moshood Olusomo Bámigbóyè's sculpture—nearly two and a half feet tall—of a priestess of Oya, the Yorùbá goddess who guards the gates of death. The Encyclopedia of African Religion calls Oya death’s opposite: she stands at the cemetery gates, admitting new souls.

View full image

Courtesy Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History

Moshood Olusomo Bámigbóyè's sculpture—nearly two and a half feet tall—of a priestess of Oya, the Yorùbá goddess who guards the gates of death. The Encyclopedia of African Religion calls Oya death’s opposite: she stands at the cemetery gates, admitting new souls.

View full image

Courtesy Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History

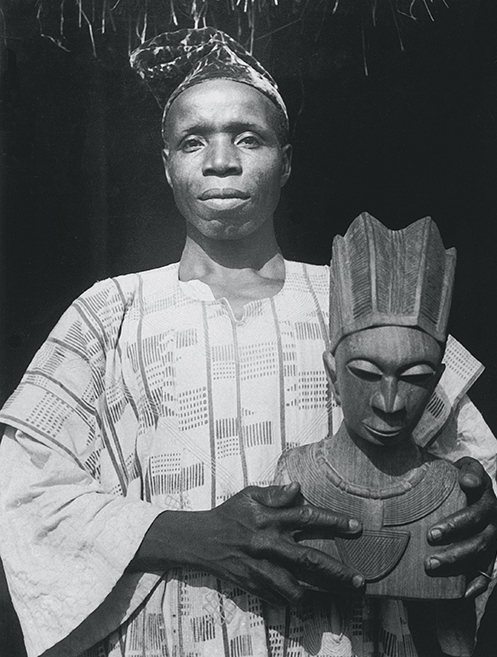

The master sculptor Moshood Olusomo Bámigbóyè is shown holding one of his works.

View full image

Courtesy Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History

The master sculptor Moshood Olusomo Bámigbóyè is shown holding one of his works.

View full image

This sculpture depicts a priestess of Oya—wife of the thunder god Sango—riding in state, surrounded by her courtiers. She holds a square fan in one hand and a sacrificial rooster in the other. On her left are a trumpeter and soldier; on her right, a drummer and a male and female couple.

The wooden sculpture was carved and painted by the Nigerian artist Moshood Olusomo Bámigbóyè, likely in the 1920s or ’30s. It is one piece of many

in the first monographic exhibition of his work at the Yale University Art Gallery, on view now and until January 8: Bámigbóyè: A Master Sculptor of the Yorùbá Tradition. This particular piece is the launching point of the exhibit and a longtime favorite of students and public alike, ever since the Gallery’s acquisition in 2006 as part of the bequest of Charles B. Benenson ’33 to Yale. (See: archives.yalealumnimagazine.com/issues/2004_09/benenson.html.)

The sculpture’s connection to Oya is made clear by the presence of a number of the attributes of Oya’s husband, including the inverted double-headed celt symbol seen on the forehead of the rider. During ceremonies, Sango priests wore their hair in the “women’s fashion” and carried satchels in worked leather; seated behind the rider in the sculpture, a priest wears a leather bag over his shoulder and has his hair arranged in the high style (agogo or àgàbà) typical of the majority of the artist’s depictions of women.

The equestrian priestess’s calm composure is conveyed by her perfectly balanced posture and the fan she holds in her right hand. In Yorùbá society, fans have deep religious and political significance, an association also seen in the art of neighboring Benin. According to the scholarship of Robert Farris Thompson ’55, ’65PhD (1932–2021), professor emeritus of African American studies and former Colonel John Trumbull Professor of the History of Art at Yale, the fan is also affiliated with cool-headedness in leadership—an idea further enhanced by the addition of blue pigment, a color extensively employed in Sango ceremonies, along with the white chalk also seen here. In Sango rituals, women “with shaven heads painted indigo and one with their head painted white” supported the priest, while another served in the symbolic role of the “wife” of Sango. This figure, with a half-shaved head dyed blue, is seated in front of the priestess, holding the horse’s reins.

Such precise attention to details of dress and adornment in his carving attests to the fact that Bámigbóyè had set out to create in this work not only a sophisticated portrait of a ceremony in action, but also one that would have been instantly recognizable to its original audience. Through the accurate depiction of clothes and hairstyles, as well as the material culture associated with the worship of Oya and Sango, the artist grounds the work in the reality of contemporary religious devotion.

Originally commissioned for a shrine setting, the sculpture was first displayed in the United States in 1976, one year after the artist’s death. The exhibition, curated by Roslyn Walker, was dedicated to African images of female power. Walker would go on to organize the first monographic exhibit at any American museum that was dedicated to a Yorùbá artist. She presented Olówè of Isè: A Yorùbá Sculptor of Kings at the National Museum of African Art in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, in 1998.

Now, twenty-five years after that trailblazing show, the Yale Art Gallery is exhibiting the second US monographic exhibition on the work of a Yorùbá artist. This masterpiece of the Gallery’s collection is the centerpiece of a comprehensive examination of the artist’s career: all the major works by Bámigbóyè—some twenty-nine works in total—are reunited for the first time, along with the finest examples of textiles, beadwork, and leatherwork of the kind depicted in his carvings.

loading

loading