Chris Cassidy

Chris Cassidy

Hiroyuki Ito / Getty Images

In 2010, the Eroica Trio, with Richard Stoltzman ’67MusM, performed Olivier Messiaen’s “Quartet for the End of Time” in the Rubin Museum of Art.

From left to right: Susie Park (violin), Erika Nickrenz (piano), Sara Sant’Ambrogio (cello) and Stoltzman (clarinet).

View full image

Hiroyuki Ito / Getty Images

In 2010, the Eroica Trio, with Richard Stoltzman ’67MusM, performed Olivier Messiaen’s “Quartet for the End of Time” in the Rubin Museum of Art.

From left to right: Susie Park (violin), Erika Nickrenz (piano), Sara Sant’Ambrogio (cello) and Stoltzman (clarinet).

View full image

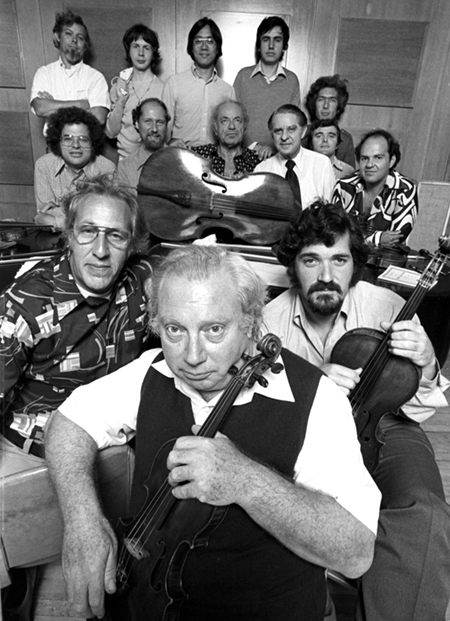

Jack Mitchell / Getty Images

When they were younger: a group portrait of musicians for an “Isaac Stern and Friends” concert in September 1976. Stern is in front. Behind him are David Soyer and Pinchas Zukerman. The rest of the group: Itzhak Perlman, Michael Tree, Alexander Schneider, Leonard Rose, Jean-Bernard Pommier, Jaime Laredo, John Dalley, Yefim Bronfman, Arnold Steinhardt—and, second in the back row, the young Stoltzman, next to Yo-Yo Ma.

View full image

Jack Mitchell / Getty Images

When they were younger: a group portrait of musicians for an “Isaac Stern and Friends” concert in September 1976. Stern is in front. Behind him are David Soyer and Pinchas Zukerman. The rest of the group: Itzhak Perlman, Michael Tree, Alexander Schneider, Leonard Rose, Jean-Bernard Pommier, Jaime Laredo, John Dalley, Yefim Bronfman, Arnold Steinhardt—and, second in the back row, the young Stoltzman, next to Yo-Yo Ma.

View full image

Chris Cassidy

Chris Cassidy

Chris Cassidy

Stoltzman and Mika Yoshida, his wife. She plays drums, marimba, and piano, and, among many other musical doings, she coaxed a jazz piece for the two of them from Chick Corea.

View full image

Chris Cassidy

Stoltzman and Mika Yoshida, his wife. She plays drums, marimba, and piano, and, among many other musical doings, she coaxed a jazz piece for the two of them from Chick Corea.

View full image

Richard Stoltzman admits that he is not usually nervous meeting new people. The clarinetist can think of only three exceptions: Woody Herman, Pablo Casals, and Fred Rogers.

Herman, toward the end of his fifty-year career, wanted someone to take over the solo in Igor Stravinsky’s Ebony Concerto, composed for Herman and his Thundering Herd in 1945. Stoltzman ’67MusM remembers awkwardly blurting out how he wished that his father, an amateur saxophonist and Herman fan, could have lived to see him meet the bandleader. Still, Stoltzman got the nod, recording the work and touring with the band. And his 1992 visit to Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood proved congenial: Stoltzman brought along a linzer torte, evidence of the baking hobby that, to his slight embarrassment, had become the human-interest focus of his publicity. Rogers turned it into a sly lesson—proof that, as Stoltzman recalls with delight, “Daddies can cook, too.”

Casals—a cellist who had played for both Queen Victoria and John F. Kennedy, a fierce defender of human rights and democracy after his exile from Francoist Spain—was more gnomic. Stoltzman met the legend at Marlboro, the summer music festival in Vermont. After a performance of Schubert’s F-major Octet, the players passed Casals, listening from his well-cushioned armchair just offstage. Stoltzman, then 26, felt Casals tug on his shirt, and knelt down to hear the 91-year-old Casals tell him, “You are a great musician.”

Stoltzman, well aware of how much he still had to learn, didn’t dare tell the other musicians what Casals had said. Even now, he tells the story with a mixture of pride and apprehension. But the comment from Casals, both a compliment and a charge of responsibility, stayed with Stoltzman. “It sustained me.”

Stoltzman pads around the basement of his Massachusetts house, which is crowded with the accumulated tokens of a life in music: posters, clippings, scores, photographs. He shares the upstairs with his wife, Mika, a frequent musical partner. (Her marimba and a piano take up most of the living room.) But downstairs is Stoltzman’s lair—“I don’t have to keep it clean.” He’s looking for a picture of Keith Wilson, his teacher at Yale. Instead, Stoltzman finds another photo, a memento of a concert in Wilson’s honor featuring former students. Illness kept Wilson from the event, so the participants posed for a group shot: a dozen or so clarinetists laughing as Stoltzman, in the corner of the frame, makes a face, sticking out his tongue.

That’s the public Stoltzman, a big personality, playing to the audience, his heart on his sleeve. His charisma propelled him to unprecedented opportunities and honors: the first woodwind player to win the Avery Fisher Prize; the first clarinetist to give a solo recital at Carnegie Hall; the first clarinetist to win a Grammy as a featured classical soloist (for his 1982 recording, with pianist Richard Goode, of Brahms’s clarinet sonatas). He’s headlined some of the most storied symphony halls in the world. Richard Goode, of Brahms’s clarinet sonatas). He’s headlined some of the most storied symphony halls in the world. He’s played for Johnny Carson and Oscar the Grouch.

The clarinet itself can be ebullient, even brazen, cutting through the thickest ensemble like a piercing giggle. But then it turns soft-spoken, pensive, the notes shaded to a fine wash, hovering at the edge of silence—a Stoltzman specialty. It’s mercurial, like the element: liquid and solid, soft and bright, weighty but nimble. In an uncanny way, Stoltzman resembles his instrument. At home, reminiscing, the showman turns quiet and thoughtful. After every story (and Stoltzman has many), he pauses to reflect, as if to return the anecdote to its place along the zigzag path of an unusual career.

A small table covered with hundreds of clarinet reeds sends Stoltzman back to Yale, to a lesson with Wilson—“in his huge office in Hendrie Hall,” Stoltzman says, spreading his arms in emphasis. Stoltzman mentioned that he wanted to learn how to make his own reeds. “I don’t do that,” Wilson said, but he had a handbook on reed-making by a clarinetist named Kalmen Opperman. Stoltzman paid a visit to Opperman in New York. It was another turning point. “I went in for a lesson on making reeds,” Stoltzman recalled, “and stayed until the end of his life.”

Opperman, who had spent years playing in Broadway pit orchestras, approached music with an unyielding zeal. He asked Stoltzman to play, and, even before a note had sounded, began critiquing the manner in which Stoltzman assembled his instrument. Up until that point, Stoltzman’s approach to the clarinet had been diligent but not particularly devout. With Opperman, Stoltzman swallowed hard and took the plunge. It wasn’t a question of whether Opperman took you on as a student, Stoltzman says; it was “if you accepted him as a teacher.” Opperman’s eye and ear were exacting and unforgiving, his scrutiny thoroughgoing. “He would criticize everything,” Stoltzman says. “Your playing, your attitude”—his eyebrows go up—“your choice of wives.” His studio, Stoltzman recalls, was decorated with bits of paper on which Opperman had jotted down his favorite pronouncements. If there aren’t good reeds in heaven, I’m not going. And another: Each of us has his own way of destroying himself. Some choose the clarinet. Under Opperman’s watch, Stoltzman rebuilt his technique from the ground up.

After Opperman’s gravity pulled Stoltzman out of Yale’s orbit, another teacher pulled him back, at least indirectly. In 1969, Stoltzman was living in New York, freelancing, when he received a phone call from Mel Powell, who had led Yale’s composition department while Stoltzman was there. Powell was coming to New York; would Stoltzman like to have lunch? Powell suggested Chinese. Over stir-fry, Powell made his pitch: move to California, where Powell had just been named dean of the music school at CalArts, and teach clarinet.

Stoltzman had enrolled in Columbia’s doctoral program, but stalled after finishing his coursework: “I was supposed to write a thesis, something about the place of the clarinet in contemporary music, but I just didn’t want to do it.” The prospect of a regular salary—four thousand dollars a year—and the California sunshine were enough.

It wasn’t the most glamorous job. Stoltzman’s residence abutted the Southern Pacific railway, and “If the train stopped in front of my house, I didn’t go in to teach that day.” But it had its benefits. Stoltzman had only a handful of students—“I had a lot of free time”—and Powell had recruited one of Stoltzman’s Yale friends. The new bassoon teacher was Bill Douglas ’68MusM, a Canadian polymath, pianist, and composer with deep interest in both avant-garde and jazz. Stoltzman took to hanging out in Douglas’s office, playing through music and improvising: hours of musical exploration, interrupted only by the pool outside Douglas’s window, where the swimmers were frequently nude. (“Bill was quite distracted,” Stoltzman claims, “I, less so.”)

Stoltzman saved up a little money to record A Gift of Music (1973). Douglas assisted, playing piano on two of his compositions. Even as Stoltzman’s career evolved from counterculture serendipity to commercial stardom, the connection stayed. Stoltzman’s first nonclassical album, Begin Sweet World (1986)—mixing jazz, new age, and folk influences into a sound uncannily evocative of Stoltzman’s fervent-yet-airy personality—again featured Douglas as composer and performer.

In the meantime, Stoltzman renewed another acquaintance, with pianist and composer William Thomas McKinley ’69MusAM. The two had met at Yale when Stoltzman performed in Attitudes, a bracing, modernist flute-clarinet-cello trio McKinley wrote while studying with Powell. While Stoltzman refined his technique with Opperman and other colleagues, McKinley was honing his own compositional voice, an amalgamation of classical tradition, avant-garde temerity, and jazz proficiency. When the two reconnected in the mid-’70s, after McKinley joined the faculty at the New England Conservatory of Music, the chemistry was profound. McKinley would eventually compose over two dozen works for Stoltzman: concerti, sonatas, chamber works—“the music of my life,” Stoltzman says.

A typical story: as Stoltzman and Mika started performing together more, she suggested asking McKinley for a new piece. Stoltzman hesitated, preferring to wait until he could offer McKinley an appropriate commissioning fee. But a chance meeting at the supermarket sealed the deal: Stoltzman offering a few hundred dollars, McKinley grunting his assent among the groceries. “A few weeks later,” Stoltzman says, “Tom showed up with this enormous manila envelope.” Instead of the single piece Stoltzman had expected, McKinley produced Mostly Blues, a suite of duets that grew to twenty-one movements.

Stoltzman’s career is a string of high-profile engagements, recordings, firsts, and successes. But to hear him tell it, his music comes from all his relationships, these meetings, these connections, unfolding across time. When Stoltzman made his Carnegie Hall solo debut in 1982, he was mindful of that history, the works that great composers of the past had written for the great virtuosos of their eras. He finished the recital with a set of homages to Benny Goodman—including pieces and arrangements by McKinley, Douglas, and Powell.

As an undergrad at Ohio State, Stoltzman had been assigned to collect and catalog a list of chamber works featuring the clarinet. He diligently typed the particulars of each entry onto index cards. He still has one of those cards, a souvenir of his introduction to a work that became a talisman: Olivier Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin du temps, a quartet “for the end of time,” an incantatory masterpiece composed while Messiaen was confined to a German POW camp during the Second World War.

Not that Stoltzman knew any of that at first. “I hadn’t heard it, and they didn’t have the score in the library,” he says. “It was just a title.” But the title was evocative enough that years later, at Marlboro, where students could choose a work to rehearse and explore over a summer, Stoltzman picked Messiaen’s quartet. He performed it at one of Marlboro’s Wednesday night recitals, held in the dining hall for an audience of faculty and students. Another listener, Stoltzman later learned, was sitting outside by a window: Peter Serkin, son of Marlboro’s cofounder Rudolf Serkin, and already a celebrated pianist in his own right. Serkin, too, was fascinated with Messiaen’s quartet, and invited Stoltzman to visit him in New York to read through the work with a couple of like-minded friends.

It turned into a standing invitation. Both Stoltzman and Serkin were living on the Upper West Side—“I could walk there in about three minutes”—and Stoltzman would often drop by and play. Sometimes the rest of the quartet, violinist Ida Kavafian and cellist Fred Sherry, would be there, and sometimes they wouldn’t, but music would be made, whoever showed up. Eventually, the group began to perform the piece for audiences. They recorded it as well, for a 1976 LP that began Stoltzman’s long and fruitful tenure with the august RCA Red Seal label: the home of Rachmaninoff and Rubenstein, of Casals and Van Cliburn. The name the group adopted, Tashi, is a Tibetan word for good fortune. (It was also the name of Serkin’s dog.)

The group’s countercultural aura led it, in January 1976, to the Bottom Line, a New York nightclub better known as a venue for rock and blues. Stoltzman’s performance of the quartet’s third movement, the Abîme des oiseaux, a long clarinet solo that runs the gamut from slow musical meditation to ecstatic swirls of simulated birdsong, prompted an “ovation,” Billboard reported: if the repertoire “was new to the attentive listeners, their enthusiasm did not reveal that gap.” The experience helped convince Stoltzman to quit CalArts and pursue a solo career full-time. But what he remembers most about the concert is that they performed twice a night, in contrast with the usual classical-music practice of single concerts. It created an informal feel that, to Stoltzman, made the music that much more present and alive. “It wasn’t this precious thing,” he says. “You weren’t worried about getting it exactly right. We just played it. And then we played it again.”

He remembers that sort of music-making—an everyday, practical magic—from his childhood. He started playing the clarinet after finding his father’s old instrument under a bed, and soon he was playing in public. He fondly recalls his service in “the Stewart Memorial United Presbyterian Church Sunday School Orchestra” in San Francisco, and is still amused by that grandiloquent name for an ensemble consisting of him, his father, and his grandmother, who “played rolled chords on the piano.” Stoltzman took to it naturally. “I wasn’t nervous,” he says. “I was with people I knew, playing for people I knew.”

That may be his guiding light: the sense of community and connection, of music as the point of contact between an individual and humanity and the universe. He’s a child of the ’60s, after all. In the liner notes for A Gift of Music, Stoltzman quoted the poet Rabindranath Tagore: “The same stream of life that runs through my veins night and day runs through the world and dances in rhythmic measures.” In 2008, after a 30-year hiatus, Tashi reunited for a concert series. Stoltzman looked out at the audience. “They were all old,” he says. “All these old hippies.” He smiles. “And I thought, These are our people.”

Stoltzman hasn’t always been so well received by his fellow clarinetists, some of whom cavil at his onstage flamboyance, his spontaneous interpretations, his use of vibrato—often considered verboten in classical clarinet playing. (Stoltzman shrugs it off—“vibration is life”—and notes that Wilson, too, used vibrato.) Then again, opening doors is not a job for the shy. Stoltzman tells another story, about hearing a recital by Harold Wright, the longtime principal clarinetist of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, a legendary figure among clarinetists. After the show, Stoltzman went backstage, waiting in a long line of fellow players, all of whom were in awe of Wright’s technical prowess. But when Stoltzman reached Wright, the elder player recognized him and said, matter-of-factly, “You actually made it.” Stoltzman had achieved the solo stardom to which other classical clarinetists had long aspired.

Stoltzman is both proud of his résumé and cognizant of how much it has been a product of not just skill, but also serendipity and luck. He remembers a colleague, a principal clarinetist with a major orchestra, picking his brain about pivoting to a solo career. Stoltzman’s advice: you have to find an agent, you have to say “Yes” to every opportunity, you have to travel a lot, and still, you have to simply hope for the best.

Also: “You have to find a partner who will support you,” he says. “Who will take care of you.” His first two marriages ended in divorce; in 2012 he married Mika Yoshida. “She keeps me alive,” he marvels. They have released two recordings as a duo, both with a wide overlap between the jazz and classical realms. Mika, who plays drums, marimba, and piano, coaxed a jazz piece for them both from Chick Corea, and a double concerto from composer Michiru Ōshima. Stoltzman is now working on new pieces by guitarist Pat Metheny and bandleader Miho Hazama.

There’s also still music by McKinley—now memorials, the composer having passed away in 2015. “I miss him a lot,” Stoltzman says, emotion clouding his voice. Serkin, too, is gone, having died in 2020. Stoltzman remembers receiving, a year and a half before Serkin’s death, an iPhone video Serkin made of himself at an outdoor, out-of-tune piano, a public art installation on a Maine sidewalk, playing Bach, utterly committed, utterly transported, making music as if it were the only thing in the world: “His hands quivering with intensity.” It’s clear Stoltzman feels the loss, not just of the man, but of that energy.

For a long time, Stoltzman didn’t teach. But he’s returned to it in recent years, mostly coaching students on specific works. (Occasionally, the path is reversed: so many students were coming to him with Elliott Carter’s Gra, an intricate, complex stretch of modernism, that Stoltzman was compelled to learn it. Finding a jazzy, impish wit within the music’s algebra, he grew to like it a great deal.) But he worries that technology’s isolated immediacy can forestall the engagement with other musicians and listeners that help make the repertoire their own. “They all come in with the accompaniments on their phones,” he laments, a particular dismay for someone who rarely, if ever, plays the same piece the same way twice. He can show them technique, he can show them phrasing, but some things they need to figure out on their own: “Not how you play but why—why are you doing this piece? What is it that you want to say?”

At Marlboro, Stoltzman recalls, Peter Serkin used to sit in on master classes, observing or even lending a hand as a piano accompanist. At first, Stoltzman was nonplussed. “I said, ‘You’re already better than these guys.’ But Peter knew that maybe they didn’t have the same form, the same technique, but they had wisdom.” It was reinforced years later, when Stoltzman toured with Herman’s band. “I learned a lot,” he says. “The older generation—they had this knowledge.”

He remembers Keith Wilson, playing the Brahms Quintet, seamlessly melting into the ensemble’s sound. He remembers rehearsing the same piece with the Amadeus Quartet, and how, at a particularly dramatic shift in harmony, the four players would instinctively rise out of their chairs together, coming down as one on the harmony’s resolution. He remembers Woody Herman’s pride in birthing Stravinsky’s score, and his determination to see it outlive him. He remembers Kal Opperman, his severity, his dedication. He remembers Pablo Casals tugging on his shirt. He remembers the composers, the performers, the friends, the encounters, the connections. It’s points in time, filtered through the heart, riding the breath, reaching the ear. It’s music.

loading

loading

1 comment

-

Chuck Klein, 10:07am January 14 2023 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.Dick, my high school classmate, played Amazing Grace for our 25th reunion in 1985. His performance was most stirring, apropos and still remembered by all. Richard is also the reason for my re-introduction to a girl I had had a date with in high school; we were both attending his guest soloist appearance with the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra in 1995. We’re still married. Richard’s Frank Lloyd Wright style home in Cincinnati was spectacular and where he and his son gave impromptu duets to entertain party guests. See ya at the next reunion. Chuck Klein, Woodward H.S. Class of 1960.