Bob Handelman

Bob Handelman

Michael Marsland

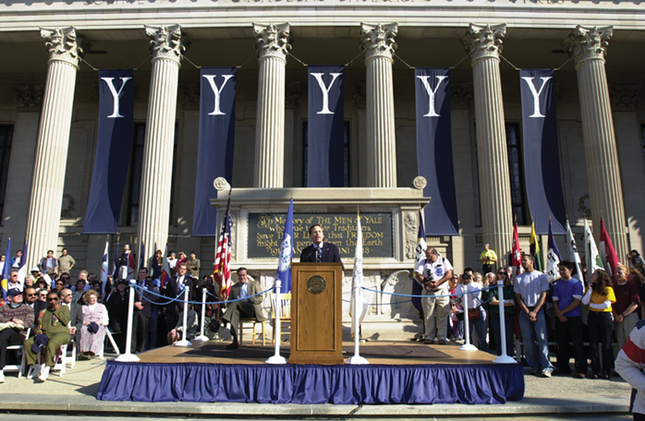

President Levin delivering the Tercentennial Welcome Address. Yale’s 300th birthday celebration started early, on October 21, 2000, for Parents’ Weekend.

View full image

Michael Marsland

President Levin delivering the Tercentennial Welcome Address. Yale’s 300th birthday celebration started early, on October 21, 2000, for Parents’ Weekend.

View full image

Levin throws a pitch. He had joined a softball team with other graduate students in economics at Yale.

View full image

Levin throws a pitch. He had joined a softball team with other graduate students in economics at Yale.

View full image

There’s no information in Yale’s archives about what Levin had just said. But it’s clear that Sterling Professor Marie Borroff ’56PhD and Kurt Schmoke ’71 enjoyed it.

View full image

There’s no information in Yale’s archives about what Levin had just said. But it’s clear that Sterling Professor Marie Borroff ’56PhD and Kurt Schmoke ’71 enjoyed it.

View full image

San Francisco: 1947–1964

I grew up in a middle-class Jewish family in the Marina District, where we had a restorative view of the bay, the hills of Marin County, and the Golden Gate Bridge from our third-floor deck.

My mother was a perpetual optimist, and my father a highly ethical businessman in a line of work (the liquor business) where that was a rare quality. My mother taught me by example to be a warm and sympathetic listener, and to see the best in people. My father taught me by example to live by the biblical prescription to do justice, to love mercy, and to walk humbly. Their lessons made a deep impression.

I fell in love with baseball at age seven. This passion made me an avid reader. I read every baseball book in the public library and memorized the baseball encyclopedia. In later life, I could hold my own in baseball trivia one-on-ones with the likes of Bart Giamatti ’60, ’64PhD, Don Kagan, Tom Beckett, and—those of you who patronize Phil’s barber shop on Wall Street will appreciate this—Carl McManus. I still know more about baseball than I do about any other single subject. Apart from motivating me to become a reader, baseball conferred another useful intellectual advantage. I became a master of mental arithmetic, able to update batting averages quickly by dividing three-digit numbers in my head. I translated this fluency with numbers into what finance professionals and venture capitalists have told me is an uncanny ability to scan, spot, and interpret errors and anomalies in budgets and balance sheets.

Baseball, and permissive parents, gave me independence—much more than middle-class kids enjoy today. From the time I was nine or ten, my brother Steve and I were allowed to go by ourselves to Funston Field (now Moscone Field), a large park at the end of our block with three baseball diamonds. We played in pickup baseball games from late morning until dinner most summer days. If there weren’t enough players to field full teams, we’d play five on a side and hit only to one field. Or we’d play a two-on-a-side game we called “Seals and Oaks,” after the two local minor league clubs. When I was eleven, the Giants moved to San Francisco and played for two years in the old, centrally located Seals Stadium.

Steve and I would take the municipal bus on our own, a 30-cent roundtrip, and sit in the bleachers for $1.50.

My parents insisted that I learn the value of work. In summers I bagged and delivered groceries, served hamburgers and French fries at a takeout window, and unloaded boxcars. I came to respect my adult coworkers for their hard work and their commitment to making a better life for their children. It made me a small-d democrat for a lifetime.

I loved school, and I got a superior education in San Francisco public schools, in an era in which California public schools were the best in the nation. Two intimidating English teachers at Lowell High School—Anne Wallach and William Worley—taught me how to write crisp, concise sentences, and history teacher Dominic Zasso taught me how to structure an argument. Jack Anderson, our debate coach and public speaking instructor, made me into a competitive debater and a state finalist in original oratory. Our report cards contained two columns—one for academic performance and the other for “citizenship.” I only once complained about a grade: I asked Mr. Anderson why he had given me a “satisfactory” rather than an “excellent” mark in citizenship, spoiling an otherwise perfect report card. He seized the card from my hand, and, without changing the grade, wrote: “This student is a fine American!”

Stanford: 1964–1968

At Stanford, I found my passion for intellectual life, and in Jane I found the love of my life. We met as sophomores at the Stanford campus in Florence, Italy, where we were introduced to the visual arts and architecture, which—along with Mozart, ballet, and rock ’n’ roll—are passions that we have shared for more than fifty years. In Florence, one of our professors was Lorie Tarshis, who had studied with Keynes at Cambridge. Tarshis introduced me to economics. More importantly, he modeled the life of a professor—immersed not only in his own field, but also in visual art, music, and literature. It was then that I decided I wanted to be a professor, a choice my father could not understand. He thought it self-evident that I would be a lawyer.

At Stanford I not only discovered a passion for ideas and the arts, but also, I developed my ability to listen and empathize. Of course, my mother was a good listener and a deeply empathetic person who always saw the best in others, but I didn’t see myself as developing these attributes until I encountered—and began to model myself after—my freshman counselor, Jim Donovan, who went on to become a clinical psychologist. Jim was intense and passionate, but he, too, listened deeply, empathized, and saw the best in others. I began to appreciate the value of understanding other people, how they were different, what motivated them, and why what they said wasn’t always what they meant. This led me to take a deep dive into reading Freud during my freshman year and the summer thereafter. I wrote my 1994 freshman address about Jim and what he taught me, surprising him as he sat in the audience as the parent of a new Yale undergraduate.

After our two quarters in Italy, Lorie Tarshis wanted me to jump immediately to graduate courses in economics, but I resisted and chose to major in history instead, because at that point I preferred reading and interpretation to doing problem sets (perhaps confirming my father’s intuition). I studied modern European and American history mostly, but I found myself drawn to intellectual history and political philosophy as well. I read enough Marx to lead a reading group of first-year students when I served as a freshman counselor in my junior year, but I was never a Marxist. My own politics were shaped more by progressive social democrats, classical liberals, and Isaiah Berlin’s preference for foxes over hedgehogs.

That said, I was not unaffected by the times. I was never an activist, but I was something of a fellow traveler. Jane and I picketed the Oakland Induction Center to protest the Vietnam War, and I participated in the occupation of the Old Student Union in the spring of 1968, learning a fundamental lesson that equipped me for responding to such situations in later life. The lesson: don’t let them order pizza.

Oxford: 1968–1970

Jane and I got married ten days after graduation and we went off to two glorious years at Oxford, escaping the political turmoil that was America in 1968. Sensing that they had an aspiring academic on their hands, my Merton College history tutors immediately assigned me to archival research. I quickly discovered that being an historian was very different from being a history major. I loved reading, interpreting, and arguing about the work of historians, but creating history from archival materials was a lonely business. When asked later why I switched from history to economics, I would joke that I was allergic to the dust in the Bodleian library, but actually I was allergic to the solitude.

I wanted an intellectual pursuit that was more engaged with people and the world, so I decided that I would pursue a PhD in economics. But not at Oxford. Economics programs in the US were better, and Oxford was a paradise for humanistic studies.

My history tutors arranged for me the privilege of meeting with Isaiah Berlin near the end of Michaelmas term. After a mesmerizing conversation, he declared that he would love to take me on as a student, but he was leaving Oxford in January for a year in Vienna. He advised me to spend the balance of my first year reading analytic philosophy, to sharpen the precision of my thinking, and then to do a thesis on Max Weber during my second year before returning to the US to study economics. It was great advice.

Analytic philosophy did indeed sharpen my thinking and writing. My weekly papers for Jonathan Cohen came back awash in red ink, highlighting the imprecision of my thought and language. I feared after six months that I was making no progress at all, when in my last paper I analyzed and supported Karl Popper’s argument that the future of scientific knowledge cannot be predicted. The paper came back with only one comment: “Well done, but the argument is anthropocentric.” Puzzled, I asked for further clarification. Cohen replied: “What you say may be true for human beings, but it might not hold for intelligent beings on another planet.” I think he was telling me that I had made a convincing argument, but I should not get overconfident.

Although my B.Litt. thesis on Max Weber had a narrow focus, in my reading and reflection I immersed myself in his deep and subtle examination of the connections among religion, social order, economic behavior, and the law—not only in Western Europe, but also in China, India, and ancient Palestine. In my subsequent career—with Weber in the background and having read nearly all of Freud on my own—I was never in danger of believing that human beings behave as rationally as the economic models describe.

Jane and I applied to PhD programs during the winter of our second year in Oxford. I didn’t look remotely like a PhD applicant in economics, since I had taken only two economics courses as an undergraduate, and no math courses beyond calculus. Inexplicably, I won an NSF (National Science Foundation) graduate fellowship, ensuring me full funding for three years anywhere I was admitted, but I still must have seemed risky to admissions committees. I was rejected at Harvard and MIT, but Jane and I were thrilled to be accepted at Yale. Alas, two days later I received a telegram informing me that my letter of admission had been sent in error!

Perplexed and distressed, I called Bill Parker, then Yale’s Director of Graduate Studies, who said I should just come and not worry about it.

Over time, I came to suspect that Bill Parker, an economic historian who tried repeatedly to recruit me to his field, was responsible for the first “mistaken” letter, and that some Graduate School dean had caught him out. I confronted Bill at his retirement party two decades later, and he smiled in a way that made denial implausible.

Yale: 1970–1974

From the moment Jane and I came to Yale in 1970, our lives have been blessed. In scale and cultural resources, Yale is an almost perfect academic community. We started a family in graduate school. Jane delivered our second child a week after submitting her dissertation, and then took time out to raise our children for 15 years before joining the faculty to teach—essay writing first, and then Directed Studies for nearly 30 years. Our four children have given us more happiness than we could have imagined—more than any of the accomplishments I will go on to describe.

I loved graduate school from beginning to end. There was so much to learn about my new discipline, and even with a heavy course load the first two years, there was abundant time to read and explore. The experience confirmed my earlier intuition that being an economist was less isolating than being an historian. My classmates and I studied together, worked collaboratively on problem sets when permitted, taught each other, and “talked economics” all the time. We were socialized to a profession of collaboration.

For me, the highlight of graduate student life was the economics department’s softball team. I joined in the summer of 1971, and after a couple of years of admitting graduate students who had played varsity baseball in college, we began to dominate the Yale intramural leagues in both slow-pitch and fast-pitch softball. We even left the Yale slow-pitch league for a couple of years to challenge ourselves by playing in the New Haven Industrial League. In the fast-pitch championship in 1980, I went into the final inning having pitched an 8–0 shutout. After a leadoff walk, Danny Rye, who later became chair of the geology department, hit a colossal home run to deep center field, shattering my dream of a shutout. On the day I was appointed president, the Yale Daily News interviewed Danny, asking him what he remembered about me as a softball player. His response was: “He was competitive.” Naturally, given my early attraction to baseball statistics, my every at-bat, hit, run, inning pitched, and run allowed is recorded and deposited in the Yale presidential archives.

The precocious professor Joe Stiglitz accelerated my progress toward the PhD. In the spring semester of my second year, a classmate and I took a directed reading course with Joe. The experience was exhilarating—an hour a week watching the young master at the blackboard work thorough models, or create entirely new ones before our eyes. By the end of the semester, I was prepared to write a dissertation. Under Joe’s supervision, I wrote a theoretical paper on the relationship of technical change, scale economies, and market structure, and by the spring of my third year, I completed a second paper extending the theory. I then worked, under the supervision of Dick Nelson ’56PhD, to seek evidence that bore on the theory—digging deeply into the engineering literature on four chemical industries in the 1950s and 60s.

In the summer of 1974, as I was transitioning to a faculty position, Jane and I were invited to dinner by Ray and Sophie Powell. Ray, an economics professor who specialized in the economics of the Soviet Union, wanted us to meet another young faculty couple, Dick and Cindy Brodhead. Dick ’68, ’72PhD, had been Ray’s bursary student in the mid-1960s, when Ray was chair of the economics department. Ray opened the evening with these startling words, addressed to Dick and me: “I wanted you to get to know one another, since the two of you will be running Yale some day!” It was my first premonition, and surely Dick’s as well, that leadership roles were in our future. Ray could not have known that nineteen years later the two of us would begin a felicitous partnership that blissfully extended for eleven years, until Dick decided it was time to become a president.

Teaching

In the fall of 1974, despite never having taught a class on my own, I was assigned to be director of Economics 10, Introductory Microeconomics—a course taught in small sections by a staff of seventeen. In search of ideas for improving the course, I consulted those with experience in running similar courses. I learned a lot from Marge Garber, then an assistant professor in the English Department, who directed English 25. (She is now an English professor at Harvard.) I decided to join her in an experiment she planned to undertake: videotaping each of the instructors so that they might learn how to improve their leadership skills in presentation and discussion.

Videotaping was not Econ 10’s only foray into technology. The next year, we experimented with computerizing the problem sets. We designed the problem sets by thinking carefully about how students might go wrong, so that each incorrect multiple-choice answer had a plausible logic behind it. Students received a personalized printout that told them in detail why their correct answers were correct and why their wrong answers were wrong.

I didn’t enjoy teaching graduate classes very much. In their first year or two of professionalization, most graduate students seemed to lack the intellectual curiosity of undergraduates. But the dissertation gave greater scope for originality.

I loved helping students learn to identify a topic, define an approach, work with data, and think and write clearly. Sixty-two of my students completed dissertations between 1975 and 1995.

Research

After my dissertation, my research concentrated on two themes. In the mid-1970s deregulation was in the air. Joe Peck advised me to pick one industry that was likely to be deregulated, and then to become an expert on that profession. I chose railroads. Over a five-year period, I wrote a series of papers that culminated in a large, disaggregated simulation model predicting the effects of deregulation on railroad rates, profitability, and consumer welfare. My predictions were circulating in prepublication form before the Staggers Act (which deregulated freight railroads) passed in May 1980.

Next came a return to the economics of technological change. I took a deep dive into the semiconductor industry, where I learned, among other things, that government programs to advance technology were most effective when the government itself was the consumer of the product (as it was with the earliest semiconductors and computers). This finding had profound implications for how the United States might seize and maintain global leadership in emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and quantum computing. The Chinese seem to have learned this lesson from our history; we seem to have forgotten.

I also focused on two under-conceptualized and under-explored primitives—i.e., ideas that have not been much studied—that drive the rate of technical change and the evolution of industry structure: technological opportunity (when the conditions make innovation more or less possible) and appropriability (the extent to which private sector firms capture the benefits of their investment in innovation). To understand how opportunity and appropriability differed across industries, Dick Nelson ’56PhD, Sid Winter ’64PhD, law professor Al Klevorick, a small army of graduate students, and I undertook a large-scale survey of industrial R&D (research and development) executives in 130 industries. What came to be known as “The Yale Survey” has been widely cited and the data have been used in scores of subsequent studies.

In both my teaching and research there was a discernible pattern that is characteristic of the way I approached future leadership assignments. With each new role or challenge, I would plunge in and learn the facts, primarily by reading, but also by listening to those with relevant experience, expertise, or insight. Once immersed, I would frame the questions to be addressed, develop a strategy, and mobilize a team to execute the work.

My work was good—thorough, well-written, and more grounded in empirical context than the work of most in my field—but it was not earth-shattering. Despite the presence of strong supporters and mentors, tenure was never a certainty.

Nonetheless, I suffered very little anxiety. I attribute this to the two most important women in my life. My mother instilled in me self-confidence, optimism, and calm. In situations that others perceive as crises, I invariably have confidence that things will work out. And I knew that whatever happened, Jane would support me. Rather than pursue an academic career in English, Jane had chosen to care for our children, an activity that she loved more than any other. I loved being a father, too, but Jane made the overwhelmingly larger investment of time and emotional energy, freeing me to pursue my career however I chose. She supported every career decision I made, however much my work took me away from her and the children. I also knew that if I failed to get tenure, she would make things work out wherever we went. When I later chose the very public role of president, Jane, despite being a very private person, adapted and became a beloved public partner—widely admired for her graciousness and enthusiasm by faculty, students, and alumni.

Extramural engagement

Among the considerations that led to my choice of economics over history was the opportunity for engagement with the world outside the academy. And sure enough, such opportunities came early and often. I advised railroads and testified before the Interstate Commerce Commission on the competitive impact of proposed railroad mergers, and I testified in several important antitrust cases and patent disputes in other industries as well.

Of all my extramural engagements, I most enjoyed working for Major League Baseball. In early 1989, just as Bart Giamatti was taking office as Commissioner, we sat in my backyard on Everit Street and he pitched me on helping him to solve baseball’s fundamental economic problem—that of the competitive imbalance between teams in large, lucrative media markets and those in smaller cities. He hired me as a consultant, and over the summer I worked out schemes for revenue sharing and payroll taxes. In the fall, after Bart’s fatal heart attack, I presented these ideas to both the owners and the players’ union negotiators. The players were highly skeptical, and the ideas went nowhere, only to resurface and be adopted a decade later, when I joined George Mitchell, George Will, and Paul Volcker on Bud Selig’s Blue-Ribbon Panel on Baseball Economics.

My outside work greatly enriched my understanding of business decision-making. It also prepared me well for the presidency. Before I was 40, I had become comfortable working with high-level business executives, lawyers, and government officials. And the experience of being an expert witness in high-stakes litigation—requiring one to communicate clearly, credibly, and truthfully—was superb preparation for subsequent interrogation by alumni, student activists, the press, the Yale Corporation, and the Yale College faculty.

University service

My first opportunity for high-level university service came in 1978-79, when I was asked by Provost Abe Goldstein to serve on a committee to examine the effects on Yale of a new state law eliminating mandatory retirement for faculty and staff. It was my first exposure to serious deliberation about serious university matters by serious people. I learned that good decisions can be reached by thoughtful and conscientious people who put the interests of the institution first.

My introduction to true university statesmanship, however, came a year later, when Deans Lamar and Thomson appointed me to the Ad Hoc Committee on Faculty Appointments. In my eulogy for Jim Tobin, I described what I had learned:

I was fortunate early in my career to serve on the committee that came to bear [Jim’s] name, charged in 1980 with reconsidering all aspects of the procedures and criteria for the appointment and promotion of faculty. For Jim, such a task demanded the same high level of intellectual rigor and moral seriousness as any work of scholarship. The Tobin report is more than a set of recommendations. It is a wise and learned treatise on how a great university develops its faculty, and how it should fairly balance such competing considerations as demonstrated scholarly achievement, future potential, teaching, and citizenship. The report is as clear, logical, and coherent as any Tobin lecture or article. For me, however, the enduring significance of the Tobin Committee was not the content of its report, but the method of its work. If a question is worth asking, it is worth bringing to bear the full power of one’s intellect and the full range of one’s moral sensibility.

I endeavored to carry this lesson to all my subsequent committee assignments and administrative roles. (For more, see “James Tobin: Scholar-Hero,” The Work of the University, Yale University Press, 2003, p. 199.)

More assignments followed, notably serving on, and then chairing, the Committee on Cooperative Research, Patents, and Licensing, as well as serving as Director of Graduate Studies in the Economics Department. In the spring of 1987, then-President Benno Schmidt offered me the position of Dean of the School of Organization and Management, but, as a humanist turned economist, I told Benno my heart was in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. Two weeks later Benno asked me to become chair of my beloved Department of Economics. That was an instant yes.

Before assuming the chair on July 1, I employed a practice I would use later on when becoming dean, president, and startup CEO, and which, as president, I urged on those I appointed to leadership roles: start with a listening tour. I met individually with each and every one of the department’s 45 faculty members—in their own offices. People are more comfortable, and more open, on their own turf than in the chair’s office or in Woodbridge Hall. I practiced the kind of deep listening which I had learned from my mother, trying to understand empathetically how every constituent saw the landscape, what bothered them, and where they felt they could make a constructive contribution.

There was tension in the department between those privileged with membership in the Cowles Foundation for Research in Economics—mostly theorists and econometricians—and those excluded. It was also clear that the department was slipping; many worthies had retired or departed, and we had only a handful of mid-career “stars.” We needed an influx of distinguished senior talent. Thus, internal reconciliation and external recruitment became my top two priorities.

With Al Klevorick’s tactful leadership at the Cowles Foundation, and with deputy provost Charles “Chip” Long’s unfailing support, we were able to eliminate the historical disparity between Cowles and the rest of the department in resources provided to junior faculty. This was a tremendous accomplishment, because the two-tiered system had seriously impaired our ability to attract young faculty who weren’t members of Cowles. We also opened Cowles affiliation to any interested member of the department, which greatly reduced resentment. Within a couple of years, tension within the department virtually disappeared.

To tackle recruitment, I analyzed the market by preparing “depth charts” modeled on football teams. In every field of economics, I listed our faculty, both senior and junior, noting those likely to retire in the next few years. At each “position,” we listed potentially recruitable senior faculty working elsewhere, whose presence would increase the department’s standing and attract strong students and other faculty. Having a visible depth chart also helped guide discussion concerning where we should allocate new or vacated slots, rather than having the customary free-for-all in which everyone advocates increasing the representation of his or her own field. Ultimately, analysis and opportunism led to success. We made three spectacular senior appointments in my first two years.

Bringing harmony to a divided faculty and recruiting superstars were valuable preparation for the presidency. But even more valuable were my daily tutorials. Bill Brainard ’62PhD had returned to the economics department from the Office of the Provost, and, to my surprise and delight, he accepted my request to become Director of Graduate Studies. We were neighbors on Everit Street, and on most days we either walked or drove home together, testing plans or reflections on the events of the day against Bill’s wisdom and experience. These conversations often continued into early evening as we stood on the sidewalk in front of Bill’s house.

By the time I began my second term as chair, in the fall of 1990, the economics department was flourishing; I was enjoying teaching senior seminars on antitrust law and economics and on US industrial competitiveness; I had former graduate students placed at Stanford, Chicago, Carnegie-Mellon, Duke, Northwestern, Dartmouth, and elsewhere; and Sciences Po held a conference in Paris devoted to the Yale Survey, featuring scholars from all over Europe who were using the data in their work.

But the university was in trouble. Benno Schmidt had wisely decided that the decades-long decline of our physical plant needed to be reversed with an aggressive and sustained program of renovation and improvement. But Benno and his team were unable to see a smooth, nondisruptive path that could lead there. In February 1991, Provost Frank Turner convened a group of twelve leaders of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and charged us with developing a plan to reduce the size of the faculty by fifteen percent. I was stunned by the recklessness of this mandate. I had sat on the University Budget Committee since 1986, and I had as clear a picture of our finances as anyone in the University. To me, it seemed obvious that a smoother course was possible: the desired profile of facilities investment could have been realized by reducing faculty and staff by five or six percent, restructuring our debt, and tweaking the target rate of spending from the endowment. Alas, this approach was ruled out of bounds by the provost and we were told to focus on how best to achieve a fifteen percent reduction in the number of faculty slots.

None of us were happy with our charge, and we refused to develop a plan calling for a fifteen percent reduction. Nor would we endorse the provost’s suggestion that we eliminate sociology and engineering. Dick Brodhead notably remarked: “One could have a twenty-first-century university without the study of society and technology. But why would one want to?”

The provost then lowered his target, and we reluctantly presented him with a plan for achieving a reduction of 10.7 percent. To a person, the twelve of us were delighted when the Faculty of Arts and Sciences appointed its own committee to study our recommendations. Our son Daniel, then sixteen, called this group—run by Tom Carew, a professor of psychology and biology—“the committee to restructure the restructurers,” providing our family comic relief in grim times. (I think Daniel enjoyed the idea that his father and friends were going to be “restructured.”) In early March, the Carew committee recommended a responsible reduction of 5 percent, and the provost settled on 6.6 percent.

The last mile

Just as the Carew report was being discussed, I was visited in New Haven by two trustees from my alma mater: Jim Gaither, chair of Stanford’s board of trustees; and John Lillie, chair of its presidential search committee. We had a lengthy dinner, engaging in wide-ranging discussion of higher education, Stanford, and Yale. The chemistry seemed excellent, even exuberant. When asked whether I would consider a move to Stanford, I did not say no. At the end of the evening, Jim, who later recruited me to the board of the Hewlett Foundation, put his hand on my shoulder and seemed to say: “Young man, you will go far.” Two weeks later, Stanford announced the appointment of Gerhard Casper as its eighth president.

The conversation with Stanford had a profound effect on me. I was aware that I had the capacity for high-level university service, but I had always imagined that, with my quantitative facility and penchant for strategic thinking, the natural job for me was provost. Colleagues in the economics department—Dick Cooper, Bill Brainard, and Bill Nordhaus ’63, ’73MA—had served in that role for ten of the previous twenty years, and I had little trouble imagining myself doing what they did. But presidents were different, or so I thought. My models were Kingman and Bart, and I could not imagine myself having the public presence or self-confidence of Kingman, nor the eloquence or wit of Bart. But after the Stanford interview, I began to think that I might be capable of more than I had imagined.

In the third week of May, Benno gave me a great gift. Without a hint of his own plans, Benno asked me to become Dean of the Graduate School. Five days later, after informing the Corporation that morning, Benno called to say that he was leaving Yale and that the Corporation would soon name an acting president for the year ahead. By elevating me from department chair to dean, he had given me a shot at his job.

I was not able to accomplish much in my nine-month tenure as Dean of the Graduate School. My major preoccupation was fending off efforts by Locals 34 and 35 to unionize our graduate students. In addition to having many planned and unplanned encounters with the student leaders, I brought together faculty in small groups to discuss how unionization might affect their departments and programs. I also gained valuable experience by chairing meetings of the divisional senior appointment committees, attending meetings of the FAS Executive Committee, and interviewing faculty in departments where the chair’s term was coming to an end.

Meanwhile, the Presidential Search Committee, chaired by the calm and gracious Rev. Robert Lynn, was quietly at work. I was among the hundreds of faculty, alumni, and outsiders interviewed by members of the committee in the summer of 1992. Then I heard not a word for the next seven months. Finally, on February 5, I got a call asking if I could meet with a couple of other members of the search committee in New York City. In the two months that followed, I had 24 interviews, each involving one or two conversation partners, until I had met at least once with every member of the search committee and all the remaining Fellows of the Corporation. It seemed clear that the Corporation did not want to make a mistake.

From my perspective, having this much exposure to my future partners in the governance of Yale was an unqualified good, despite the long period of uncertainty.

Finally, Bob Lynn asked if he might visit me on Everit Street and meet Jane on the evening of Tuesday, April 8. The three of us had a long chat in the living room. Bob closed the conversation by saying: “The Corporation will be meeting next Monday. You might want to get started on drafting an acceptance speech.”

The announcement event on April 15 was memorable. My remarks were well received, and the faculty present were more than relieved; they were jubilant that the job had gone to one of their own. But our children were astonished. Looking at the Fellows of the Corporation arrayed behind me as I spoke, they noticed that Bob Lynn was 6 feet 10 inches tall, Bill Kissick was 6’ 6”, Vern Loucks 6’ 5”, Henry Schacht 6’ 4”, and John Lee, the greatest of Yale basketball stars, was 6’ 3”. They asked: “How did they ever pick you, Dad? You’re so short.”

loading

loading

1 comment

-

CHARLES SHANA, 11:56pm May 04 2023 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.Loved this reflection.

Especially as I listened to it with "Fanfare for the Common Man" in the background.