"Interesting Events in the History of the United States," 1832

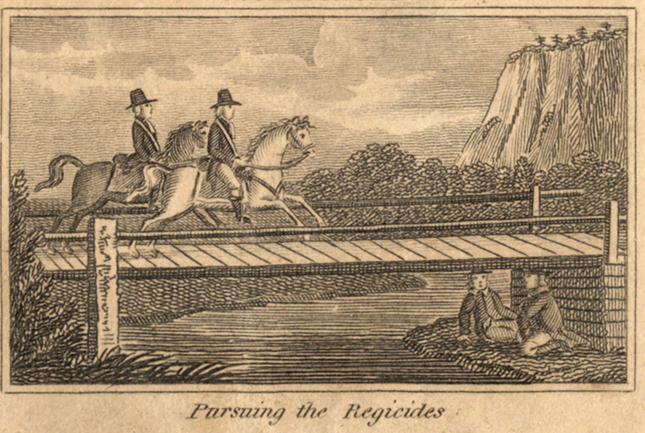

An illustration from an 1832 book depicts a legend recounted in Ezra Stiles’s book about the regicides. Whalley and Goffe were said to have hidden under a bridge near East Rock, as their pursuers rode above.

View full image

"Interesting Events in the History of the United States," 1832

An illustration from an 1832 book depicts a legend recounted in Ezra Stiles’s book about the regicides. Whalley and Goffe were said to have hidden under a bridge near East Rock, as their pursuers rode above.

View full image

Mark Alden Branch ’86

Judges Cave, where Whalley and Goffe hid, is now a popular attraction in West Rock Ridge State Park.

View full image

Mark Alden Branch ’86

Judges Cave, where Whalley and Goffe hid, is now a popular attraction in West Rock Ridge State Park.

View full image

The coronation of King Charles III of the United Kingdom, scheduled for May 6, will probably not have any significant consequences for Yale and New Haven. But the ascension of Charles II, in 1660, triggered an episode that is a central part of New Haven lore: the story of the “three judges”—Edward Whalley, William Goffe, and John Dixwell—who were wanted for killing a king.

The homicide of King Charles I came after seven years of war between Charles’s forces and those of Parliament, led by Oliver Cromwell. Whalley, Dixwell, and Goffe were among many commissioners in an ad hoc court that tried Charles for treason and among the 59 who signed his death warrant.

Whalley was an important officer in Cromwell’s army, and also Cromwell’s first cousin. Goffe, also an officer, was married to Whalley’s daughter. They both served in administrative and military positions in Cromwell’s government. Dixwell was less prominent but had served in Parliament and Cromwell’s army.

Upon the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Charles II sought his revenge. Of the 59 who had signed the warrant, 21 were dead by the time of the restoration. Of those still living, 25 were found guilty of treason. Nine were executed, some in grisly public spectacles in which they were hanged, drawn, and quartered. It’s no wonder that 12 more of the commissioners fled. Most went to Europe. Whalley, Goffe, and Dixwell opted for New England.

It was in some ways a sensible choice. Puritan colonists in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Haven shared the religious and political views of the regicides, and were mostly eager to protect them. Whalley and Goffe went first to Boston, where they appeared openly in worship services and other public settings. But locals loyal to the King soon sent word back to England, and as the chance of their being arrested increased, the pair decided to try a more remote settlement: New Haven.

In 1661, the New Haven Colony was still separate from Connecticut. Under cofounder John Davenport, it was known as an unusually pious and strict Puritan community. When Whalley and Goffe arrived in New Haven on March 7, Davenport welcomed them into his own home. They stayed there for nearly two months before moving into the home of another colonist.

Two months after their arrival in New Haven, a pair of Boston Royalists who had been deputized to serve an arrest warrant came to the colony in search of Whalley and Goffe. They arrived first in Guilford, where they entreated deputy governor William Leete to help them search for the regicides. Leete insisted that he could not assist them without consulting the other local magistrates; he also pointed out that the Sabbath was soon approaching, so they could not travel. New Haven officials used further bureaucratic stalling tactics over the next several days while Whalley and Goffe escaped into the countryside.

Whalley and Goffe went to the top of the ridge that is now called West Rock and found a rock formation—now known as Judges Cave—in which they would have some minimal protection from the elements. They used the cave off and on over the next three years; they also hid for more than two years in a basement in Milford. In 1664, they moved somewhere considered safer: the remote frontier town of Hadley, Massachusetts, where they hid in the house of pastor John Russell.

The two remained there for more than decade under a kind of self-imposed house arrest. Whalley died around 1675; Goffe later moved to Hartford and died around 1680.

Perhaps in part because he was a less valued target, Dixwell was far more successful as a fugitive than his fellow regicides. He fled to Germany in 1660 and apparently spent several years there. His first known appearance in America was in 1665, when he spent some time with Whalley and Goffe in Hadley. By 1672, he was living in New Haven under the name James Davids. He married and had three children, living quietly but not in hiding.

A resident later remembered that Dixwell’s “cloathing, deportment and manifest great education and accomplishments, in a little time caused many to conjecture the said gentleman was no ordinary person.” He died in 1689.

In 1794, Yale president Ezra Stiles published the first book about Whalley, Dixwell, and Goffe. Stiles positioned the judges as spiritual comrades to the American revolutionaries a century later: “intrepid and patriotic defenders of real liberty.” Since then, their story has been represented in histories, paintings, and novels. And of course—as anyone who has navigated the confluence of streets near Payne Whitney Gymnasium will know—the judges are remembered in three major thoroughfares: Whalley Avenue, Goffe Street, and Dixwell Avenue.

loading

loading