The book I’ve been reading lately weighs 5.5 pounds, has 960 pages, stands 12 inches tall and 9 inches wide, and when it’s lying on a flat surface, the pages stack up to nearly two inches. I can’t help wondering: is it even heavier in hardcover?

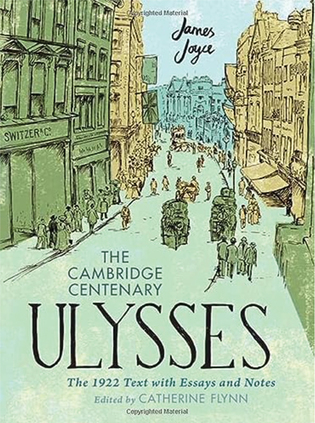

But that’s my sole complaint. My hat is off to Catherine Flynn ’09PhD, who is now an English professor at UC Berkeley. The tome she has assembled and edited—with essays by 18 professors, including herself—includes 30 illustrations, 18 maps, and 18 chapters. Each chapter incorporates an essay written by an expert about one of the most unusual books ever written: James Joyce’s Ulysses.

I read parts of Ulysses in college. It was like nothing I had ever read before—confusing, no quotation marks, and a story that seemed to wander around in a daze. Take the very beginning:

Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the

stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a

mirror and a razor lay crossed. . . . He held the bowl

aloft and intoned:

—Introibo ad altare Dei.

[I will go in to the altar of God.]

Why would a man treat his shaving bowl like a sacred urn? We are definitively in medias res. Or consider one of the three major characters, Leopold Bloom, making a biblical joke while deciding on a snack:

Sardines on the shelves. Almost taste them by

looking. Sandwich? Ham and his descendants

mustered and bred there.

And why is the book so heavy? Because, in between those 18 chapters, there are reproductions of every single page of Joyce’s original 1922 volume. There were many misspellings in that text, which I assume is at least one reason why the book is so tall and wide; Flynn needed room at the sides and underneath so she could note corrections. For instance: “for news-paper read newspaper” and “for suspened read suspended.”

Flynn also worked with Ronan Crowley, another Joyce devotee. (At the end of the list of the 18 chapters is a modest note—“The Errata: Ronan Crowley and Catherine Flynn.”) He wrote about the “Circe” chapter of the book, in which Bloom follows Stephen Dedalus into a brothel in a fatherly effort to keep him safe. Circe is a witch, so it makes sense that her chapter is written as if Bloom were on LSD. At one point, Joyce describes him thus: “Barefoot, pigeonbreasted, in lascar’s vest and trousers, apologetic toes turned in, opens his tiny mole’s eyes and looks about him dazedly.” Thirty-eight crazed pages later, a “Dummymummy” shouts “Bbbbblllllbbbbblblobschbg!” (Anyone reading this longest and wildest chapter might also feel they’re on LSD.)

The climax of that chapter, and perhaps of the entire book, comes when Stephen (presumably drunk) sees his dead mother rise up through the floor, imploring him to pray and repent. Feeling “strangled with rage,” he shatters the chandelier and runs away, Bloom hurrying after him. They wind up with Stephen outside, sleeping it off, and Bloom watching over him. At the end of that chapter, Bloom—perhaps dreaming?—sees his long-dead baby son, now “a fairy boy of eleven.” The boy “Gazes unseeing into Bloom’s eyes . . . . He has a delicate mauve face. On his suit he has diamond and ruby buttons.” Bloom calls out, silently, “Rudy!” Joyce provides no response.

When Stephen wakes up, the two start toward Bloom’s house. Joyce has a different pattern for each chapter; in this one, “Eumaeus,” he uses pompous words and long sentences that could put a person to sleep. When they reach Bloom’s home—the “Ithaca” chapter, in which Joyce asks and answers exacting questions as if he were interrogating himself—they drink chocolate and discuss music. But when they step outdoors to see the constellations, Joyce delivers an ethereal description of the night sky: “The heaventree of stars hung with humid nightblue fruit.”

Bloom offers Stephen a place to sleep, but Stephen decides to go home. Bloom walks upstairs and crawls into bed beside his wife, Molly, an opera singer. He knows she had sex with another man that day. He kisses her rump anyway. The final chapter is Molly’s long, barely punctuated stream of thought, which ends with her memory of their first lovemaking. Is it a sign that she still loves him? Joyce won’t tell.

loading

loading