The Iliad

Translated by Emily Wilson ’01PhD

W. W. Norton & Company, $39.95

Reviewed by Greg Ellermann

Today, even for those who have been spared direct involvement, war feels unnervingly close to home. There may be no better time, then, to read (or reread) the great epic of war, The Iliad, which appears in a remarkable new translation (2023) by Emily Wilson. As Wilson observes in her fine introduction, The Iliad speaks of irreparable loss as much as conquest, communion in grief as much as vengeance. These deeply humane themes are worth revisiting now.

In Wilson’s vibrant, formally accomplished verse, the Homeric narrative of the Trojan War attains a striking immediacy. Lines of iambic pentameter—the verse form also used in Wilson’s celebrated 2017 The Odyssey—move quickly, something like the “swift-footed” Greek hero of the poem, Achilles. The language is clear and direct throughout. Never too contemporary, it often feels timeless the way that classical poetry can. Wilson conveys a variety of tones: from “the cataclysmic wrath / of great Achilles” to the tenderness of friends, lovers, and family.

There is a realism in The Iliad—about bodies, feelings, nature, war, and work—that Wilson captures well. Enraged at his commander Agamemnon, Achilles’ “inmost heart / inside his hairy chest was split in two.” The poem’s famous extended similes are given ample room to breathe. In an expansive passage, the killing of a Trojan warrior is likened to the “uproot[ing]” of “an olive sapling,” carefully grown “in a lonely place— / plentiful water bubbles up around it, / and it is fine and flourishing and strong— / nodding and quivering amid the breezes / and thick with bright white blossom.” The Iliad is a poem of death on the battlefield, but it also points to the living world beyond.

Wilson notes that the Greek Achilles and the Trojan Hector are both described as minunthadios, or “short-lived.” Mortality and vulnerability transcend the lines of battle. Her comment recalls the “impartiality” that, for the philosopher Simone Weil, was The Iliad’s finest artistic and ethical achievement. A difficult ideal, but one about which this ancient poem constantly seeks to remind us.

Greg Ellermann is a lecturer in the Yale English department.

__________________________________________________________________

Fancy Bear Goes Phishing: The Dark History of the Information Age, in Five Extraordinary Hacks

Scott J. Shapiro ’90JD

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $30

Reviewed by James Ledbetter ’86

Fear of cataclysmic computer hacking goes back decades, years before the vast majority of humans had access to the Internet. Scott J. Shapiro ’90JD reminds readers of the 1983 movie War Games, in which a high school student unknowingly hacks into a military computer system and risks creating a global nuclear war.

Real-life computer hacks, Shapiro argues, are usually far more mundane and have much lower stakes. “Computer exploits are not perfect weapons,” he writes. “They are hyperspecialized weapons that are foiled by the same issues of compatibility—or interoperability—as we all are.” And in the early days of what would now be called cybersecurity crime, the motivations were often relatively innocent: hackers exposed flaws in computer systems not because they wanted to destroy institutions or shake them down for money, but rather, for fun or intellectual satisfaction. Nonetheless, these exploits can be damaging—to individuals, companies, and governments.

Shapiro combines a detailed discussion of how cyberhacking works with a compelling narrative of five hacks that illustrate how it has evolved. The splashiest was the 2005 hack into Paris Hilton’s phone account, which led to the public revelation of intimate photos. Shapiro points out that the Massachusetts teenager who unlocked Hilton’s phone did so by penetrating the primitive central computer system of her phone provider, an example of the weaknesses of early cloud computing.

Far scarier is the Russian government’s attack on the Democratic National Committee during the 2016 presidential race, which led to embarrassing email leaks that at a minimum created animosity within the party. Shapiro, a lawyer and philosopher, wants readers to understand that cybersecurity is too often treated as a problem for programmers and engineers to fix when, in fact, it invokes serious moral and ethical problems that modern society needs to discuss and resolve.

James Ledbetter ’86 is the author of several books, most recently One Nation Under Gold.

__________________________________________________________________

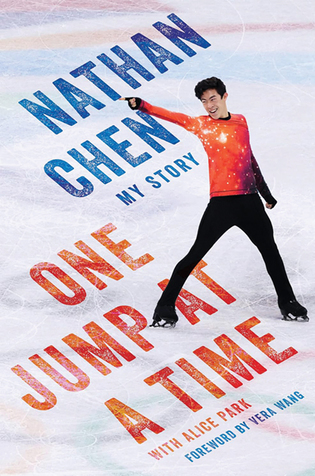

One Jump at a Time

Nathan Chen ’24 and Alice Park

Harper, $25.99

Reviewed by Philip Hersh ’68

As a journalist, I covered Yale senior Nathan Chen’s figure skating career for seven years—beginning with the 2016 US Championship. Our interactions came mainly at competitions, when the chance of an insightful conversation is rare. I had no misconceptions about really knowing Chen or his family, or what he went through in the 20 years between his first putting on skates and his winning the men’s singles gold medal at the 2022 Winter Olympics. But just how little anyone outside the shy Chen’s inner circle knew about him becomes clear on reading his illuminating autobiography, One Jump at a Time, written with Time magazine’s Alice Park.

Chen opens up in the book, writing of fears and frustrations that he kept private; about near-constant injuries he never revealed, lest they be seen as excuses; about the enormous role his mother, Hetty, played in his success; about the logistical, emotional, and financial sacrifices his parents, two brothers, and two sisters made to facilitate his skating. One chapter, titled “Dread,” takes him through the difficult months that led to his downfall at the 2018 Winter Games, where he found himself too burdened by expectations.

A month later, Chen won his first of three World Championship titles and set out on a convoluted path to 2022, one that included his first two years at Yale, the COVID pandemic, and, critically, recognizing the need to add a mental coach to his team.

Despite a lingering leg injury, Chen attacked the 2022 Olympics with the most difficult programs ever attempted in competition. To help build his confidence, Chen adopted a mantra about having fun—rather than dread—at the Olympics.

Philip Hersh ’68 has covered 20 Olympic games.

loading

loading