Manuscripts and Archives

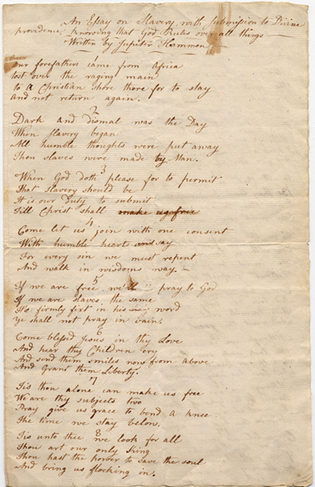

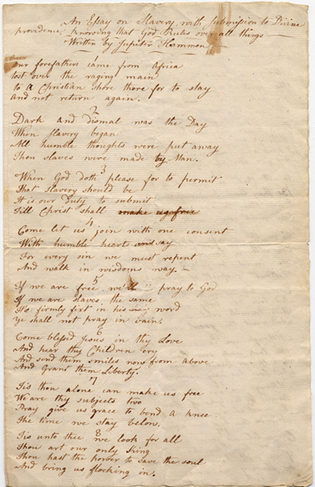

The manuscript of Hammon's “An Essay on Slavery” is in Yale’s collections; the first page is shown here.

View full image

For decades, Jupiter Hammon (1711–ca. 1805) stepped very carefully, as if he were walking on a tightrope.

On the one hand, he was one of the few enslaved Black people who were, to some degree, appreciated by their white “owners.” In his case, it was the Lloyd family. They had purchased part of Long Island and named it Lloyd Neck. (The name has not changed since then.) When Jupiter was young, he lived with—and learned to write and read with—the Lloyds and their children. He even went to school with the children when he was 12 years old. Notably, although he started by calling himself Jupiter Lloyd, he soon decided against it; he wanted to use a name from the Bible. The name was Hammon, which meant “preparation.” In other words: he was preparing to meet God.

On the other hand, surely Jupiter longed for freedom. When he was older, he began to give talks and sermons to other enslaved Black people. It must have been difficult work; you can’t possibly denounce anyone who has slaves if you are one of the slaves.

It is a great shame that while Phillis Wheatley’s poems are still widely recognized, Hammon’s poems were essentially misplaced, or lost, for decades. The poems he wrote were very good and often excellent. One of the titles is “An Essay on Slavery,” in which Hammon begins with this stanza:

Our forefathers came from Africa

Tost [sic] over the raging main

To a Christian shore there for to stay

And not return again.

The second stanza hints, carefully, at the fact that humans themselves had slashed their “humble thoughts” in order to force others into slavery:

Dark and dismal was the Day

When slavery began

All humble thoughts were put away

Then slaves were made by Man.

The third stanza quickly smooths over that suggestion, turning back to Christianity and God:

When God doth please for to permit

That slavery should be

It is our duty to submit

Till Christ shall make us free.

All of this, and much, much more, can be found in the book America’s First Black Poet: Jupiter Hammon of Long Island. It’s a book made up of many parts, by many knowledgeable people—some of whom were Yalies or librarians who had happened upon long-lost information in the library stacks. The book was edited by Stanley A. Ransom Jr. ’51, who kindly sent one to me after he had seen the short piece I’d written about George Berkeley (1685–1753) and others.

As he matured, Hammon also gave orations to his “brethren.” One of these is titled “An Address to the Negroes of the State of New-York,” and the second sentence reads: “Yes my dear brethren, when I think of you, which is very often, and of the poor, despised and miserable state you are in, as to the things of this world, and when I think of your ignorance and stupidity, and the great wickedness of the most of you, I am pained to the heart.” (I shudder to think of what his audience thought of that.) Still, he acknowledged that “I have had more experience in the world than most of you, and I have seen a great deal of the vanity and wickedness of it.”

He also produced some of his ideas for dealing with the slaves’ overlords, suggesting that “If you are humble, and meek, and bear all things patiently, your master may think he is wrong; if he does not, his neighbors will be apt to see it, and will befriend you, and try to alter his conduct.” He added that, if that didn’t work, “You must cry to Him, who has the hearts of all men in his hands, and turneth them as the rivers of waters are turned.”

In the end, I was relieved to learn that Jupiter Hammon was allowed to spend the last ten or so years of his life free from slavery. He had been manumitted.

loading

loading

1 comment

-

Jennifer Palmiotto, 11:09am September 17 2024 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.Such an inspiring and important story. Thank you for sharing.