Yale University Art Gallery

In this half-scale study for “The Hours”—a mural by Edwin Austin Abbey for the ceiling of the House chamber in the Pennsylvania State Capitol—24 figures represent the hours of the day. The nighttime hours are covered in dark shrouds.

View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

In this half-scale study for “The Hours”—a mural by Edwin Austin Abbey for the ceiling of the House chamber in the Pennsylvania State Capitol—24 figures represent the hours of the day. The nighttime hours are covered in dark shrouds.

View full image

Toledo Museum of Art

This allegorical figure of Victory was first sculpted by Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907) for his 1903 Sherman Monument in New York City. A 42-inch-high gilded bronze miniature appears in the exhibition. Notably for a monument to the Union cause in the Civil War, Saint-Gaudens’s model was an African American woman named Hettie Anderson.

View full image

Toledo Museum of Art

This allegorical figure of Victory was first sculpted by Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907) for his 1903 Sherman Monument in New York City. A 42-inch-high gilded bronze miniature appears in the exhibition. Notably for a monument to the Union cause in the Civil War, Saint-Gaudens’s model was an African American woman named Hettie Anderson.

View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

Saint-Gaudens also used African American models for his Memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts 54th Regiment (1883–93). His studies for those figures were later cast in bronze.

View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

Saint-Gaudens also used African American models for his Memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts 54th Regiment (1883–93). His studies for those figures were later cast in bronze.

View full image

State Museum of Pennsylvania

Violet Oakley (1874–1961) produced a series of murals for the Pennsylvania State Capitol. Her study for one of those murals, a depiction of Lincoln at Gettysburg from around 1911, shows a pensive and solemn leader looking toward a widow and her two children.

View full image

State Museum of Pennsylvania

Violet Oakley (1874–1961) produced a series of murals for the Pennsylvania State Capitol. Her study for one of those murals, a depiction of Lincoln at Gettysburg from around 1911, shows a pensive and solemn leader looking toward a widow and her two children.

View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

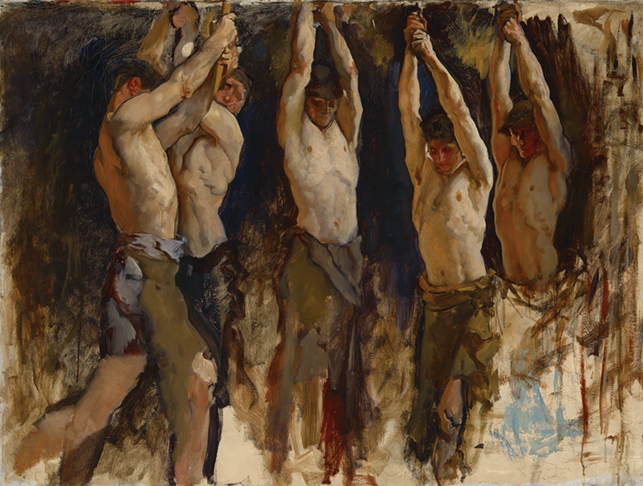

Abbey and John Singer Sargent used sketches and studies to work out their depictions of the human form. Abbey showed ironworkers around an anvil in an oil-on-canvas study for the Pennsylvania capitol mural The Spirit of Vulcan, ca. 1902–08).

View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

Abbey and John Singer Sargent used sketches and studies to work out their depictions of the human form. Abbey showed ironworkers around an anvil in an oil-on-canvas study for the Pennsylvania capitol mural The Spirit of Vulcan, ca. 1902–08).

View full image

President and Fellows of Harvard College

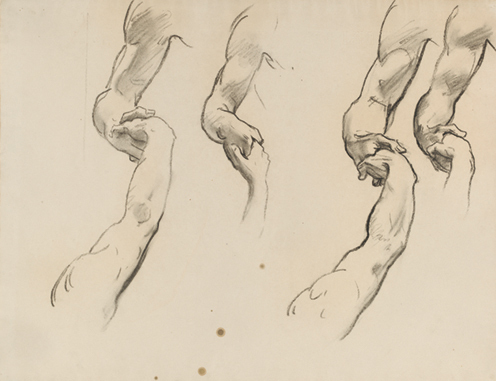

Sargent explored clasped hands in a charcoal study for a Boston Public Library mural of souls passing into heaven, ca. 1895–1916.

View full image

President and Fellows of Harvard College

Sargent explored clasped hands in a charcoal study for a Boston Public Library mural of souls passing into heaven, ca. 1895–1916.

View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

Not all of the monumental work of the era appeared in public buildings. In 1893, Henry Siddons Mowbray (1858–1928) provided a series of nine lunettes depicting muses for the New York mansion of Collis P. Huntington. Shown here is Mowbray’s study for Muse of Electricity.

View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

Not all of the monumental work of the era appeared in public buildings. In 1893, Henry Siddons Mowbray (1858–1928) provided a series of nine lunettes depicting muses for the New York mansion of Collis P. Huntington. Shown here is Mowbray’s study for Muse of Electricity.

View full image

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Painter John LaFarge (1835–1910) helped kick off the American Renaissance with his murals for Trinity Church in Boston in 1876. His watercolor study for a painting of Isaiah was one of a series of biblical figures he created for the church.

View full image

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Painter John LaFarge (1835–1910) helped kick off the American Renaissance with his murals for Trinity Church in Boston in 1876. His watercolor study for a painting of Isaiah was one of a series of biblical figures he created for the church.

View full image

In the mid-1890s, two American painters shared a studio in the rural English village of Fairford. There, the two friends worked on projects that were to be executed an ocean away, at the Boston Public Library. You probably know the name of one of them: John Singer Sargent (1856–1925). The other, Edwin Austin Abbey (1852–1911), may not ring a bell, but at that time, they were equally important leaders in a fertile period of art known as the American Renaissance.

An exhibition at the Yale University Art Gallery, The Dance of Life: Figure and Imagination in American Art, 1876–1917, explores that period and in particular the way American artists of the time treated the human figure. The exhibition, which runs through January 5, focuses on art in monuments and public buildings during the Gilded Age.

The inspiration for the show comes from the gallery’s extensive collection of Abbey’s works. His widow left the university some three thousand works in 1937—not only finished paintings, but also sketches and studies that reveal the painstaking process by which he tried to capture the human body. Mark D. Mitchell, the gallery’s curator of American paintings and sculpture, delved into the Abbey collection when he came to the gallery in 2015 and began to envision a way to highlight the artist’s work in the context of his times. “The only name people know from this era is Sargent,” says Mitchell. “We want to put Abbey into that frame where he belongs.”

Abbey began his career as an illustrator for books and magazines, and he created a series of large canvases depicting scenes from Shakespeare. His commission for the Boston Public Library, a series of murals called The Quest and Achievement of the Holy Grail, preceded a more extensive set of murals for the Pennsylvania State Capitol.

Works like these of Abbey’s and Sargent’s—along with Augustus Saint-Gaudens and other like-minded artists—imbued the monuments of an ascendant America with art that was inspired by that of the Italian Renaissance. The exhibition features sketches, studies, and other iterations of these public works, many on loan from other institutions. This allows viewers to see the process that led to the final products. “Here we’re seeing the artist in the studio developing ideas, making mistakes, making a mess,” says Mitchell. “They’re working through things like how hands hold each other, or what a sideward glance means.”

Before this time, Americans had a history of ambivalence about showing the human form, but Mitchell thinks the American Renaissance may have evolved out of a reaction to the Civil War. “It took 11 years to find any way forward artistically after the war,” he says. “Then a new generation of artists came along who lived through the war, with a new attitude toward life and the body.” Henry James, who was a friend of both Abbey and Sargent, said as much in an 1886 review of Abbey’s work in Harper’s Weekly: “Life itself is his subject.”

loading

loading