Edel Rodriguez

Edel Rodriguez

Edel Rodriguez

Edel Rodriguez

Edel Rodriguez

Edel Rodriguez

“We believe the university should divest itself of holdings in industries profiting from investments involving discriminatory practices, both here and in . . . South Africa,” wrote the Yale Daily News editorial board in January 1969. It was just one small part of an editorial concerned with Yale’s Vietnam War–related investments and calling for the university to make “high-risk investments in Black ghettos,” but it was a harbinger of things to come.

Nearly two decades would pass before Yale meaningfully divested from South African holdings, and members of the editorial board would reach their forties before non-white South Africans voted for the first time. In between, the culture of student activism at Yale and on other campuses would wane—for a while. Then, in the late 1970s, a student movement on the other side of the world resuscitated a tradition of campus activism and forced universities across the country to confront existential questions.

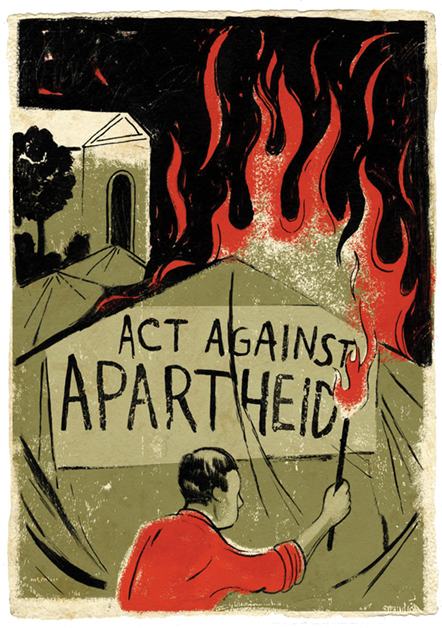

Yale’s anti-apartheid movement blossomed in the 1980s, reanimating the campus with an operatic series of events featuring symbolic shanties, mass arrests, celebrity cameos, and an actual conflagration. In the end, Yale never completely withdrew from apartheid South Africa, and there’s disagreement on what the divestment debate delivered. All agree, though, that student opposition to apartheid positioned Yale to consider its institutional identity and its role in public life in opposition to a mammoth moral evil that paid dividends.

The first stirrings

The word “apartheid” first appeared in the News in April 1953, recapping the Reverend Ray Phillips’s lecture on “apartness” at the Divinity School. Phillips had spent 35 years as a missionary in South Africa and spoke of the white government’s nascent grand apartheid schemes—which wouldn’t have been far out of place in the United States at the time—with a degree of sympathy, calling the Boers “good people who have lagged behind.”

But there is no record of anti-apartheid action at Yale until March 1960, when the apartheid state massacred dozens of Black South Africans protesting segregation in Sharpeville, inciting in earnest what would become a global movement to topple white supremacy. Within a month, Yale became the first university to host a branch of the “Emergency Relief Fund” for jailed non-white activists in South Africa, gaining the endorsement of Alan Paton, whose novel Cry, the Beloved Country remains a cornerstone of anti-apartheid literature. Later that semester, three South African Yalies denounced apartheid as “unrealistic” at a panel in Dwight Hall; a year after that, then-exiled Miriam Makeba performed in Woolsey Hall. But those inklings of resistance lost momentum to other seismic shifts in the 1960s.

Architecture critic Paul Goldberger ’72 recalls “very little if any discussion of South Africa” on campus during his years at Yale. “I’m emphatically not saying it didn’t matter,” Goldberger says. “Nevertheless, I think . . . college students, despite how worldly they like to think of themselves as being, can be quite parochial at the same time, and we were concerned about Vietnam because it represented our country, and even more to the point, arguably our own futures. And we were concerned about the civil rights movement in the United States, and issues like the Black Panther trial for the same reason.”

Activism and counterculture never disappeared completely from the scene in the 1970s, but they didn’t command the same attention on campus. In his Freshman Address in 1973, President Kingman Brewster Jr. ’41 famously called on the Class of 1977 to shake off the “grim professionalism” he had recently observed in the student body.

Aside from the odd film screening or Black Sash vigil, anti-apartheid activism lay fallow until after the Fall of Saigon. Walter “Terry” Pflaumer ’81PhD, a graduate student in African history, called out Ford-era complacency in a 1975 News op-ed, writing that “there is nothing particularly inevitable about the fall of apartheid. It could be around for a very long time, especially if we pretend it’s going to fade away.” Uncensored reports from South Africa would soon make it clear that the moral arc of the universe doesn’t bend toward justice on autopilot.

After Soweto

On June 16, 1976, thousands of Black students began marching through a township outside Johannesburg demanding an end to segregated “Bantu education.” The government had moved to impose Afrikaans—a symbol, for many, of the apartheid state itself—as the language of instruction in Black schools. Police met peaceful protesters with open fire, the image of a slain 12-year-old named Hector Pieterson hit newsstands across the world, and the government could not conceal the brutal reality of what became known as the Soweto Uprising.

That September, Yale history professor Leonard Thompson, who had left South Africa in Sharpeville’s wake, testified before Congress, urging the US to sever apartheid ties, alleging Henry Kissinger had been too lenient on South Africa. Within a year, Yale students had formally organized an anti-apartheid campaign, General Motors board member and civil rights leader Leon Sullivan introduced the racial-equity minded “Sullivan Principles” to guide corporations doing business in South Africa, Thompson became inaugural director of Yale’s Southern African Research Program, and a graduate student named Diana Wylie ’84PhD settled into New Haven.

“Those years were explosive years,” says Wylie, a scholar of African history who remained at Yale until 1994. “1977 was the year after the Soweto revolt, and it was the year Steve Biko was killed in prison. So those are my years at Yale, but they were the crucially important years for the dying and the end of apartheid.”

It was in Wylie’s first semester that students formally mounted a concerted and protracted effort to compel institutional aegis toward apartheid’s downfall. In November, the Anti-Apartheid Coalition urged Yale to divest from 13 companies operating in South Africa, particularly blue chips like IBM and General Electric who turned a profit fine-tuning its security state. The university did appoint a committee to investigate its financial interests in South Africa. But Yale made it difficult for student activists to get seats on the committee, according to a Coalition member’s op-ed in the News, which dismissed the committee as “a token and meaningless gesture to silence the Black Student Alliance at Yale and Anti-Apartheid Coalition demands.”

The Ad Hoc Committee on South Africa Investments presented its report to the Corporation in April 1978, recommending Yale implement a “gradual and incremental” framework for assessing companies’ compliance with ethical standards based on the Sullivan Principles. Per the report, the Corporation would ask companies to advocate against mandatory discrimination; if unresolved, the Corporation ought to call for the principles’ implementation at shareholders meetings; should that fail, the committee would request that the Corporation refuse purchasing new stock. The Yale College Council voted to urge divestment that week, to limited avail. Six months later, A. Bartlett Giamatti ’60, ’64PhD, was inaugurated as Yale’s 19th president amid literal calls for divestment. Tensions and stakes only grew louder and clearer from there.

Yale’s thinking was guided by a volume called The Ethical Investor, written in 1972 by law professor John Simon ’53LLB and others in response to the earliest calls for divestment. The authors characterized divestment as a last resort. “After all other corrective steps have failed,” they wrote, “[divestment reminds] us of the war movies in which the beleaguered infantryman, having exhausted his ammunition, finally hurls his rifle at the advancing hordes. It is, from his point of view, a terminal act which may help slightly.” On one extreme, the Soweto Uprising warranted terminal action. On the other, Yale had a fiduciary responsibility to bankroll its virtuous output.

Before serving as president of Amherst College—and now, the New York Public Library—Tony Marx ’81 was an anti-apartheid activist who talked his way into an internship with Yale’s vice president for finance. He remembers compiling reports on Yale’s financial interests in South Africa and sitting just outside the office of a young analyst named David Swensen ’80PhD, who would later become Yale’s chief investment officer. Summarizing Swensen’s theory of fiduciary responsibility, “Yale having more resources to do more of what Yale does,” Marx recalls, “It’s hard to argue with that, right? If you believe in Yale’s mission. But Yale’s mission is about education. . . . What you teach is partly based on what you do.” Activists and administrators would contest the breadth of that dissonance for the next decade.

In a 1979 Yale Political Union debate, South Africa’s ambassador to the United States argued that divestment would be expensive, fruitless, and compromising for Yale’s “academic autonomy.” The activists—known as the Coalition Against Apartheid from 1983 onward—persisted.

The ’84–’85 academic year wrapped up with a 300-person protest followed by a 24-hour vigil outside Woodbridge Hall. At a debate in Battell Chapel in September 1985, Swensen argued that by demanding divestment, the Coalition was asking Yale to make “a very costly symbolic gesture.” Columbia became the first Ivy League university to divest from South Africa two weeks later, and by November, ANC leader Andrew Masondo would be speaking at Yale in front of some iconic mise-en-scène: a symbolic shantytown on Cross Campus meant to replicate the squalid conditions apartheid often forced upon non-white South Africans. (These shanties, a precursor to the ones that would be built on Beinecke Plaza the following spring, were removed soon after the event.)

Wylie, who joined the Yale faculty after finishing her PhD, says she had no interest in escalation—quite the opposite, in fact. “I was not a proselytizer,” says Wylie, who recently retired as a professor at Boston University. “I was simply trying to introduce students to that volatile situation coolly and calmly, and that meant that I was not an adviser [of the Coalition].” She adds, though, that “if they asked me to do something, I would do it.”

To that end, Wylie spoke at teach-ins, marched with the Coalition at demonstrations in New York, and accompanied student leaders at talks with President Giamatti in Woodbridge Hall. Wylie stresses, though, that “the Coalition Against Apartheid was very much driven by students, who were frankly marvelous, absolutely marvelous.”

Matthew Countryman ’85, who helped spearhead the Coalition, became acutely aware of apartheid at a young age. “I was 13 when Soweto [happened] and I was in a family that paid attention,” Countryman says. His parents, Joan Countryman ’66MUS and Peter Countryman ’65, ’66MA, “met and got married as an interracial couple in the context of the civil rights movement here. So I was raised in a family that not only was committed to racial justice . . . but was conscious of and deeply involved in protest as a way to create justice.”

True to his roots, he settled into campus activism almost immediately, involving himself in nuclear non-proliferation and workers’ rights. Both came to a head in 1984, as Ronald Reagan’s reelection disappointed antiwar activists and Yale’s clerical and technical workers went on strike before reaching a landmark settlement with the university. “In the aftermath of both the settlement . . . and Reagan’s landslide, it was a moment for reflection among those of us who saw ourselves as activists,” Countryman says.

From that moment of reflection came a dual motivation to take on apartheid. “We were deeply influenced by Soweto, the national student-led divestment campaign, and the very successful public education campaign of the ANC and its affiliates . . . as well as the Free South Africa Movement here,” Countryman says. “The second agenda was to put race back on the public agenda of politics, both on campus and in the country. It was a way to talk about racial injustice at home, and we were certainly criticized for talking about some problems 8,000 miles away and not dealing with our own backyard. And yet that was a criticism we welcomed. That was sort of our point, that these things were not so different.”

In April 1986, the Coalition Against Apartheid erected a shantytown on Beinecke Plaza as the Yale Corporation prepared to have its regular meeting in nearby Woodbridge Hall. They were following in the footsteps of Dartmouth activists who had built shanties on their campus in November. The administration said the shantytown, dubbed Winnie Mandela City by its builders, could remain for one week. When protesters refused to leave after ten days, the university sent in Yale police to arrest 78 people, most of them students, and directed physical-plant managers to dismantle the shantytown. More arrests were made at protests on the following two days. In all, more than 150 people were arrested; they were the first-ever mass arrests on a campus that had not that long ago been through large-scale protests during the Black Panther Trials and the Vietnam War.

Many students and faculty decried the arrests. “It threatens the tradition of free expression and trust between students and administration at Yale,’’ Professor Vincent Scully ’40, ’49PhD, told the New York Times. “In a sense, the administration started it by tearing down the shanties.’’

Giamatti told the Times that activists were informed they could relocate Winnie Mandela City and that the university would follow the “Brewster Scenario” and dialogue with protesters. He noted that the disagreement wasn’t about apartheid: “We all agree it is an unmitigated evil.’’ University secretary John Wilkinson ’60, ’63MAT, added that “the difference between today’s students and those of the 60’s . . . is that these students are much better organized. They are much better prepared to deal in uniform action.’’

And they kept at it.

Cornel West, then an associate professor at Yale Divinity School, spoke to protesters rallying against the administration’s actions and was arrested. Hostilities extended across Beinecke Plaza to the Law School, where activists jeered at none other than Frank Sinatra. Ol’ Blue Eyes was there to give a talk about his life and career, but the protesters outside the school’s auditorium were more interested in the fact that Sinatra had performed at Sun City—an apartheid-era Las Vegas analogue—in violation of a UN-led cultural boycott.

By April 21, a new set of shanties was in place on Beinecke Plaza, with the administration’s blessing. When South African novelist and anti-apartheid activist Nadine Gordimer came to receive an honorary degree at commencement, she visited the shanties. The initial approval expired on June 1, but the shanties stayed. In March 1987, Yale president Benno Schmidt Jr. ’63, ’66LLB, announced divestment from three oil companies operating in South Africa, a far cry from Coalition demands. So the shanties stood longer still. They would remain on the plaza for more than two years, becoming a fixture on campus and keeping the issue of apartheid and divestment in the forefront.

Then came the fire

With his son in tow and years of medical practice in South Africa under his belt, Elwood Bracey ’58 came to New Haven in June 1988 simply to celebrate his 30-year reunion. That is, until he got up one morning and decided to fill a gallon-size jug with gasoline.

By Bracey’s account, he walked over to Beinecke Plaza and inspected the shanties opposite Yale’s War Memorial Cenotaph; seeing they were empty, he sprinkled the gas all over Winnie Mandela City, “and the big conflagration started.” He was arrested and released on bail before returning to face a judge. Bracey called on his college roommate to defend him in court. As Bracey remembers it, the defense’s opening statement was stoic and short. “It wasn’t that Dr. Bracey loved Yale too little,” Bracey recalls. “He loved Yale too much.”

“The judge just put up his hand and he said, ‘That’s enough . . . Bracey, why’d you do it?’” Bracey says. “And I told him the story about my Vietnam experience and how I objected to the shanties being in front of the War Memorial, and I explained my experiences in South Africa, and that Winnie Mandela was not the shining light that Yale was portraying her as. So I had my say.”

He also had admirers. Among the congratulatory letters, “one of the most shameful,” Bracey says, was a note from Robert Shelton, the former Imperial Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. “I didn’t necessarily want that, but that was part of what came back.”

“If I had to do it over again, I’d probably do it because the statement had to be made,” he says. But it was costly, not only financially, but emotionally. Some people thought that it was a terrible thing to do, but I thought it was terrible to have that eyesore.”

Apartheid’s end

The shanties were replaced shortly after the fire by a wooden “memorial wall.” Again, it was sanctioned by the administration for a short period, and again it lasted for more than two years. In the time between its installation and its dismantling in February 1991 (this time by the students themselves), Nelson Mandela was freed and the ban on anti-apartheid groups like the African National Congress was lifted.

Apartheid did not collapse overnight, though, and Mandela called for divestment activists to hold the line until democracy was realized. Meanwhile, corporations operating in South Africa shrank from 21 percent to 3 percent of Yale’s endowment by 1991, largely because companies left on their own, and the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 mostly obviated any would-be resolutions the Yale Corporation could have introduced at shareholder meetings. In 1994, South Africa held its first post-apartheid election, and Nelson Mandela became the country’s president.

Did Yale and its activists play a part in this outcome? Tony Marx thinks so. “As a major investor in companies that were doing business in South Africa,” he says, “Yale had a role. And the truth is, if you look back, when the universities started to divest . . . it was part of what changed history, and for the good.”

loading

loading