Air-Borne: The Hidden History of the Life We Breathe

Carl Zimmer ’87

Dutton, $32

Reviewed by Richard Panek

The ancient belief in miasma—air “corrupted” enough “to throw a healthy body out of balance, to spark a disease that could kill”—might seem unscientific today. But according to Carl Zimmer’s Air-Borne: The Hidden History of the Life We Breathe, so does the modern science of aerobiology, at least until shockingly recently.

Zimmer populates the first third or so of this deep history of how we think about the “gaseous ocean in which we all live” with memorable historical figures from the past few centuries as they engage in vivid disagreements about the means by which germs migrate. Surfaces? Spittle? That germs might be airborne, however, doesn’t seriously enter the debate until well into the twentieth century.

The official designation of aerobiology as the science of airborne organisms dates only to 1937. Even then, the field rested on a foundational assumption that, in retrospect, makes much of the resulting research look like the application of leeches. Aerobiologists relied on a distinction between droplet nuclei smaller than or larger than five microns; they figured that the former would be light enough to float and the latter would drop like “cannonballs under gravity.” Not until 2009, in response to the H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic, did an environmental engineer actually go looking for the primary source behind that assertion.

It didn’t exist.

Even so, a seemingly visceral resistance to the idea that germs might travel significant distances—that they might be airborne—continued to plague aerobiology, from the first Trump administration’s abandonment of Obama-era pandemic protocols, through Anthony Fauci’s initial mockery of the idea that Covid-19 germs might linger on a breeze long after a sneeze, to, in perhaps the most damning detail in this book, a World Health Organization tweet on March 28, 2020: “FACT: #COVID19 is NOT airborne.”

“The world’s relative luck held out,” Zimmer writes about the 2009 swine flu pandemic. More than a decade later, during the Covid pandemic, our relative luck held out again, thanks in part to scientists’ eventual acceptance of how germs migrate. Count your blessings, Air-Borne suggests. The next time—and there will be a next time—we might not be so lucky.

Richard Panek’s most recent book is Pillars of Creation: How the James Webb Space Telescope Unlocked the Secrets of the Cosmos.

__________________________________________________________________

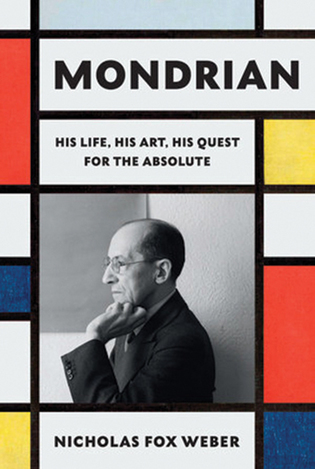

Mondrian: His Life, His Art, His Quest for the Absolute

Nicholas Fox Weber ’72MA

Knopf, $40

Reviewed by Alexi Worth ’86

Piet Mondrian, possibly the greatest abstract painter, was a quiet, penurious neat freak with few friends or interests, and virtually no romantic life. His letters are “extraordinarily pedantic,” full of sales records and “detailed accounts of his health.” Not exactly great material for a 600-page biography, you might think? But the strange thing is, Mondrian emerges from this thorough and sympathetic book as a fascinating character, a gentle visionary who was, as he himself put it, “not like other people.”

Every few pages there is an odd little anecdote that leaves the reader flummoxed and often charmed, whether it’s about Mondrian’s “peculiar style of kissing” (peculiar perhaps because he was so inexperienced), his odd stiff-backed dancing, his insistence on washing his dishes only every third day, or his white-hot fury when, in 1926, Amsterdam’s mayor considered banning the American dance step, the Charleston. “If the ban on the Charleston is enforced,” the expatriate painter wrote to a Dutch newspaper, “it will be a reason for me never to return.”

Weber, the author of previous books on Balthus, Le Corbusier, and Josef and Anni Albers, paints a vivid picture of Mondrian’s youth in the Netherlands, where his schoolteacher father, who belonged to an extreme Calvinist sect, encouraged him to design religious allegories and lurid scenes of martyrdom. Very gradually, Mondrian made his way from the Dutch countryside to Amsterdam, then to Paris, and eventually London and New York. In his later years, Mondrian lived in small apartments that were essentially 3D versions of his paintings, “white and empty, except for red, blue, and yellow painted squares.” Visitors often remembered one non-pictorial indulgence, a collection of jazz records—the inspiration for paintings like Fox Trot B, a small square canvas that Weber describes as a “summa” of Mondrian’s art, and which many readers will recall fondly as a highlight of the Yale University Art Gallery’s collection.

Alexi Worth is a painter and writer living in Brooklyn, New York.

__________________________________________________________________

How the Light Gets In

Joyce Maynard ’75

William Morrow, $32

Reviewed by Debra Spark ’84

If you can imagine two jigsaw puzzles, with virtually identical pieces, assembled to form two entirely different pictures, you’ll have a sense of what it is like to read Joyce Maynard’s How the Light Gets In, the sequel to her 2021 novel Count the Ways.

In the earlier novel, Eleanor, orphaned in her teen years, longs for a happy family. Her wishes are briefly granted after she marries handsome Cam, a crafter of wooden bowls who joins Eleanor in the farmhouse she purchased in her twenties, thanks to early success as a writer. Three children follow. We see Eleanor doting on her offspring, but also eventually blowing up at Cam’s “adulting” failures. When their youngest, Toby, suffers permanent brain damage after a near drowning caused by Cam’s inattention, Eleanor cannot forgive. Cam has an affair with the family’s babysitter, and Eleanor moves out.

How the Light Gets In revisits this history, with Eleanor analyzing her behavior even as the novel extends the story into her later years. As a successful children’s book author, she no longer has economic woes. Still, all’s not well. She’s unattached, and one of her children refuses to speak to her. Her ex-husband, abandoned by his second wife, is dying of cancer, so Eleanor returns to the farm to nurse him and care for kind-hearted Toby.

As time passes, further challenges arrive: Toby is falsely accused of pedophilia, the estranged child has a bumpy marriage to a MAGA enthusiast, and Eleanor’s relationship with a climate-change activist is thrilling but lonely. In negotiating others’ needs (and finally attending to her own), Eleanor gathers to herself a family that looks like the cracked bowls, pieced together with gold, that a deaf friend of Toby’s makes. These bowls are not just strong at the broken places, but most beautiful there.

Debra Spark’s most recent novel is Discipline.

loading

loading