Mark Alden Branch ’86

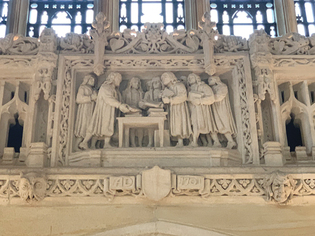

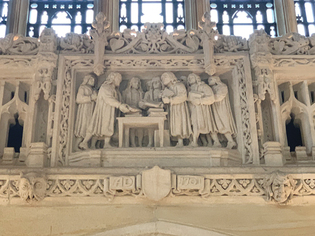

One of the stone carvings by René Chambellan in the nave of Sterling Memorial Library depicts the meeting at which ten ministers are said to have donated books “for the founding of a college.” Note the date: By 1931, when the library was built, historians doubted that such a meeting could have happened in 1700, as Thomas Clap had claimed.

View full image

“Each Member brought a Number of Books and presented them to the Body; and laying them on the Table, said these Words, or to this Effect; ‘I give these Books for the founding [of] a College in this Colony.’”

This sentence, from a history of Yale College written in 1766 by then-president Thomas Clap, is almost biblical in its importance to the college’s history. Clap’s account of a meeting of ten ministers—at the parsonage of the Reverend Samuel Russel in Branford, Connecticut—is the university’s Book of Genesis. The meeting in Branford in 1700, and the gift of “about 40 volumes of folio,” has been reenacted by students at university pageants and depicted in stone in the nave of Sterling Memorial Library.

Items from Parson Russel’s house, including the parlor doors and a table said to be the one on which the weighty folios rested, have been displayed in Sterling like holy relics. And Clap’s account is the reason that one of Yale’s residential colleges is named Branford, after the town where the college was putatively founded.

But over the last 150 years, scholars of Yale history have again and again cast doubt on the story. No written evidence of such a meeting has ever been discovered, and historians have found chronological and logistical inconsistencies that make it nearly impossible that the event could have happened as Clap, writing more than 60 years later, described it.

Why would Clap make up such a story? The presumed answer lies in a dispute he had with the colony’s General Assembly in 1763. Clap, who led Yale from 1740 to 1766, is seen by Yale historians as an effective leader who put the college on a more solid footing, physically and academically. But he also had an autocratic style of leadership, and he seemed to go out of his way to make enemies in the church, in the government, and on campus.

In 1763, one of these conflicts came to a head, and nine of his opponents petitioned the General Assembly to “exercise its powers as the creator of the College Corporation by sending to it a Committee of Visitation.” Such a committee would have the power to investigate the college and call for changes, and Clap, probably rightly, perceived that his job was in peril.

The distinction between public and private institutions was blurry in Colonial New England, where there was an established church and where the Assembly gave Yale an annual grant of 100 pounds. It was generally understood, though, that the president and trustees had authority over the college. The precedent of a committee of visitation threatened that order.

Clap argued before the Assembly that, according to English common law, it was the founders of an institution who had the power to govern it. The Assembly’s granting of a charter to the trustees in October 1701 had always been considered the college’s founding. But Clap told the Assembly an alternative story, the one he would set down in print three years later in his history of the college: that a meeting in Branford in 1700, where books were given with the express intent of founding a college, represented Yale’s true beginning.

Clap won the battle. The Assembly declined to act on the petition, though it’s unclear whether Clap’s logic or mere politics were what saved him.

Clap’s story went more or less unchallenged until 1876, when historian Franklin Bowditch Dexter, Class of 1861, examined the evidence and determined that the tale “has undoubtedly some basis in truth, but can hardly be accepted in detail.” A later university historian, George W. Pierson ’26, devoted his 1988 book The Founding of Yale to exploring the story of the Branford meeting.

After thoroughly debunking the idea of any 1700 meeting that could have been considered a founding, Pierson identified a grain of truth in Clap’s story: Ministers did donate books for the college both before and after the charter (there was a collection set aside for a future college as early as 1656), and at least some books meant for the college were probably kept at Russel’s parsonage in Branford before being transferred to Saybrook. (Pierson cited an oral tradition from two different sources who described how some of the books had been burned by concentrated sunlight coming in through imperfect glass in Russel’s parlor.)

For legal purposes, and for those who care about historical accuracy, Clap’s story raises more questions than it answers. But that grain of truth is one that Yale treasures: It is an incontrovertible fact that before it had a charter, or a building, or a faculty, or students, the college was a collection of books. And as the inscription near the entrance to Sterling reads: “The library is the heart of the university.”

loading

loading