Philip Burke

Philip Burke

Philip Burke

Philip Burke

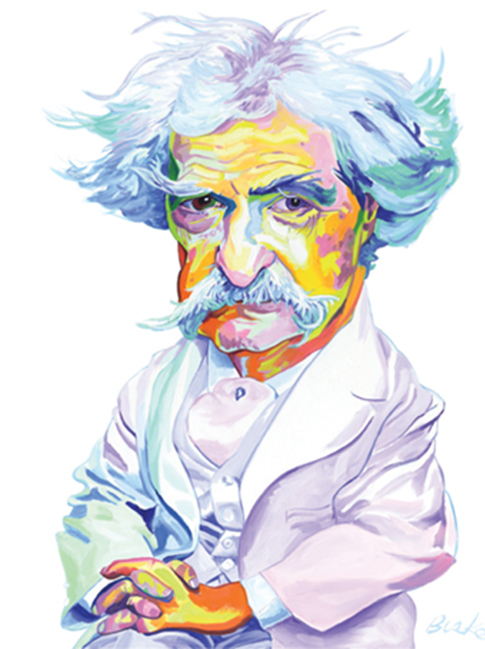

Years after some greatly exaggerated reports, Samuel Clemens really did die 115 years ago, but our fascination with the author who called himself Mark Twain clearly lives on. In 2024, James, Percival Everett’s retelling of Twain’s classic Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of the enslaved Jim, hit the bestseller lists and won a Pulitzer Prize. This year, Pulitzer-winning author Ron Chernow ’70 published his eponymous 1,200-page biography of Twain, and Stanford professor Shelley Fisher Fishkin ’71, ’77PhD, published Jim: The Life and Afterlives of Huckleberry Finn’s Comrade. And actor Richard Thomas is currently touring the country in a revival of the one-man play Mark Twain Tonight!, in the title role made famous by Hal Holbrook.

While living for many years in Hartford, Connecticut, Twain established a relationship with Yale, including two honorary degrees that allow the university to claim him as one of our own. In the following article, Fishkin—whose fascination with the author grew during her time at Yale—explores the evolution of that relationship. Twain never went to college, but his Yale ties run deep.—The Editors.

In 1868, Mark Twain was elected an honorary member of the Yale secret society Scroll and Key. It was his first formal connection to a university that would touch his life in multiple ways over the next four decades. Twain would speak on several occasions to the Kent Club, a student debating society at Yale Law School. He would attend a Yale-Princeton football game. He would allow a dozen recently graduated Yale students to convict him in a raucous mock trial during a transatlantic ocean voyage. He would give a Yale pedigree to the villain of one of his novels. One Yale student would prompt him to perform his most resonant act of philanthropy and another Yale student would be the inspiration for a central character in a play he wrote that would debut on Broadway in 2007. The university that awarded him not one but two honorary degrees would also prompt him to pen his most compelling statement of the larger moral aspirations of his humor. Mark Twain’s involvement with Yale over the course of his life and beyond is a story that needs to be told.

All roads to Yale for Mark Twain led through the Rev. Joseph Hopkins Twichell ’59, pastor of Asylum Hill Congregational Church in Hartford. The smart, athletic, public-spirited, and engaging Yale graduate had taken the job of ministering to Hartford’s most prosperous residents in 1865. In October, 1868, Twain took up temporary residence in Hartord to work with his publisher, Elisha Bliss, preparing his first travel book, Innocents Abroad, for publication. Bliss lived across the street from Twichell’s church (which Twain dubbed “the church of the holy speculators”). Shortly after Twain arrived, Bliss took Twain to an evening reception with other members of their church, where he was introduced to Twichell.

Twichell, three years younger than Twain, was educated at a private academy in New England and then Yale; he took time off from the theological seminary he entered after graduation to serve as a Union chaplain in the Civil War. Twain left school after sixth grade and spent two weeks in a unit of the Missouri State Guard that sympathized with the Confederacy. But when Twichell invited Twain to his home for dinner, their animated conversation continued long into the night. Twain wrote to Livy Langdon, the woman he hoped to marry: “I have made a friend. It is the Rev. J. H. Twichell. . . . I could hardly find words strong enough to tell how much I do think of that man.” Twain knew his friendship with a minister would help burnish his somewhat dubious credentials as a potential husband for Livy, to whom religion mattered greatly—but his enthusiasm for Twichell was sincere. Exuberant, outgoing, and blessed with a good sense of humor, Twichell quickly became Twain’s closest friend. He would officiate at his wedding; christen his children; travel with him to Bermuda, Germany, and Switzerland; and become a confidant and advisor for the rest of his life.

Twichell, an oarsman who had helped lead Yale to its first ever victory over Harvard the year he graduated, would become a trustee of Yale from 1874 through 1913. He took pleasure in involving Twain in his alma mater.

A few weeks after they first met, Twichell nominated Twain as an “honorary member” of Scroll and Key, a secret society dedicated “to the study of literature and taste.” It was an honor Twain happily accepted. He occasionally visited graduate sessions. (Six years later, in impromptu comments to students at Trinity College, Hartford, who were trying to launch an Inter-collegiate Literary Association, Twain reportedly said he’d “never been to college. The nearest he ever came was belonging to a secret society . . . at Yale College, which he called the ‘Scroll and Key’ . . . they told him all their secrets, but in either Latin or Greek—he could not tell—which he could not understand. Still as they did little but eat and drink there, he managed to sustain his part of the work.”)

At 7 a.m. on February 18, 1985, the phone rang in my apartment in Timothy Dwight College, where I was a resident fellow. “You don’t know me,” said a woman’s voice, “but I have a letter from Mark Twain that nobody knows about. I just read your op-ed in The New York Times and I know you’ll know what to do about it.” (That morning, the hundredth anniversary of the publication of Huckleberry Finn, the Times had run an op-ed I’d written about how Twain turned to satire to write about racism after being censored as a journalist when he wrote about it directly). The letter, which Twain wrote the year Huck Finn was published, contained a rare, non-ironic condemnation of racism from Twain. I was determined to authenticate it and figure out who it was to and what it was about.

A scrapbook in the Yale archives, letters to Twain at UC Berkeley, some law school records, and a range of other sources helped me piece together the story. It began with Twain’s invitation in the fall of 1885 to speak to the Kent Club at Yale Law School. The club’s president, charged with meeting Twain at the railroad station that fall, was a young man named Warner McGuinn, one of the first Black law students at Yale. He impressed Twain as someone who would make an excellent lawyer; but he was struggling to pursue his studies while holding down part-time jobs as a waiter, bill collector, and lawyer’s clerk to pay his expenses. He subsequently wrote Twain, but his letter didn’t survive. Neither had Twain’s response—until now, a hundred years after Twain had sent it.

Twain’s now-famous letter asked Yale Law School Dean Francis Wayland whether it was a good idea to provide McGuinn with support; it noted that Twain felt a special obligation to help because of McGuinn’s race. In his own private version of affirmative action, Twain ended up paying McGuinn’s expenses for the rest of his time at Yale. McGuinn won the top prize at commencement for an oration deemed “a masterly piece of work,” and he would become a prominent attorney and political figure in Baltimore and a key mentor to Thurgood Marshall.

The New York Times was incredulous when I cited the Times’s obituary of McGuinn as a source for some of what I learned: That doesn’t exist, I was told. Sure enough, it was nowhere to be found in the Times’s microfilm record. But someone had pasted it into a scrapbook belonging to McGuinn that had been sent to the Yale Archives, which is where I read it. I faxed a picture of it to the reporter. Whoever made the microfilm had not thought McGuinn was important enough to include his obituary!

Queried about McGuinn by the Times in 1985, Thurgood Marshall said he was “one of the greatest lawyers who ever lived. If he’d been white, he’d have been a judge.” The paper featured the story on its front page and his obituary is now in the Times’s digital archive. The letter is invoked whenever the question of Twain’s personal views about the role of racism in our nation’s past comes up.

In June 1888, Twain’s friend Charles H. Clark, editor of the Hartford Courant, informed him that the Yale Corporation had decided to award him an honorary master of arts degree. Twain couldn’t attend commencement, but he sent a memorable letter of gratitude to President Timothy Dwight. He wrote that “with all its lightness and frivolity,” his humor had “one serious purpose . . . and it is constant to it: the deriding of shams, the exposure of pretentious falsities, the laughing of stupid superstitions out of existence.” Whoever “is by instinct engaged in this sort of warfare,” Twain added, “is the natural enemy of royalties, nobilities, privileges & all kindred swindles, & the natural friend of human rights & human liberties.” The letter remains the most compelling statement we have from Twain about the larger moral goals of his humor.

Sometimes, of course, Twain was just having fun. In a speech he wrote for the Yale Club of Hartford (but did not deliver), Twain pretended that some students had told him the Yale degree made him “head of the governing body of the university,” entailing “very broad and severely responsible powers.” He outlined the changes he would make to the department of astronomy (as well as classics and mathematics): “I found the astronomer of the University gadding around after comets and other such odds and ends,” he said, “—tramps and derelicts of the skies . . . I told him it was no economy to go on piling up and piling up raw material in the way of new stars and comets and asteroids that we couldn’t ever have any use for till we had worked off the old stock. At bottom I don’t really mind comets so much, but somehow I have always been down on asteroids. There is nothing mature about them; I wouldn’t sit up nights the way that man does if I could get a basketful of them. . . . I felt obliged to stop this thing on the spot; I said we couldn’t have the University turned into an astronomical junk shop.” (It’s worth noting that the Yale Club of Hartford did eventually end up hearing the speech: Samuel Clemens ’97, Twain’s great-great-great-grandnephew, delivered it at the club’s 140th anniversary party, held this past April at the Mark Twain House.)

During the summer of 1892, Twain traveled to Europe on the steamship Lahn, along with a dozen Yale students who had recently graduated. The main entertainment was putting Twain on trial in an admiralty court convened by the captain on the charge that he was, “in his capacity as a storyteller, an inordinate and unscientific liar.” The Yale students were impaneled as jurors, with Lee McClung ’92, captain of the undefeated 1891 football team, as foreman. A newspaper reported that Mark Twain, in chains and handcuffs, sat in the prisoners’ dock as witnesses read excerpts from Twain’s books as evidence and while the “very solemn” jury of Yale students looked on. Twain’s defense was insanity, and two ship physicians testified that “in all their experience, they had never met a man who talked irrationally as Mark Twain did.” Twain was convicted. The sentence? “Read for three hours every day from his own works until the steamer reached port.” Twain called the sentence “a slow and horrible death”—but served it faithfully, entertaining the passengers with readings for the rest of the voyage.

We don’t know which of the many Yale students Twain met over the years was the inspiration for the main character in the play Twain wrote six years later. Twain wrote Is He Dead? A Comedy in Three Acts in Vienna as he emerged from a very dark period of his life, the result of a crippling bankruptcy and the tragic death of his beloved daughter Susy. By February 1898, Twain had paid off his debts and was finally ready to come out of mourning. He celebrated by writing a wild, over-the-top, cross-dressing farce that satirized debt and death—as well as how value is created in the art world.

The play begins with the following “Memorandum”: “The handsome young gentleman (a bright Yale student) of whom ‘Chicago’ is an attempted copy, was full of animal spirits and energies and activities, and was seldom still, except in his sleep—and never sad for more than a moment at a time, awake or asleep. He had a singular facility and accuracy in playing (imaginary) musical instruments, and was always working off his superabundant steam that way. He could thunder off famous classic pieces on the piano (imaginary) so accurately that musical experts could name the pieces. He imitated the flute, the banjo, the fiddle, the guitar, the hand-organ, the concertina, the trombone, the drum, and everything else; and for a change, would ‘conduct’ a non-existent orchestra, or march as a drum major in front of a non-existent regiment. If I have not made him a clean and thorough gentleman in this piece, I have at least strenuously intended to do it.”

In the play the character nicknamed “Chicago” is a key member of an international band of struggling young artists in Barbizon, France, friends and disciples of the French painter Jean-François Millet (but the play departs radically from facts known about the real artist). Due to the machinations of an evil art dealer, they can’t sell their paintings and are on the verge of starvation. Knowing that the work of dead artists commands much higher prices than that of living artists, the desperate young men decide to change their fortunes by faking Millet’s death. At that point Millet reappears as his own sister, the Widow Daisy Tillou, come to town for the funeral.

When I read the play in manuscript in the Mark Twain Papers at the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley in 2003, I found myself laughing out loud in the archives. But the clever, effervescent high-spirited romp was never published, despite the fact that Twain—and Livy—both thought it was good. I decided to rescue it from obscurity. I published an edition of it in 2003, and helped guide it to Broadway in 2007, adapted by the talented David Ives ’84MFA and directed by the celebrated Michael Blakemore. The character based on the Yale student Twain had known was played by Tony award–winning actor Michael McGrath, and Millet/Widow Tillou was played by Tony award–winning actor Norbert Leo Butz.

Variety called it “an elaborate madcap comedy that registers high on the mirth meter and reaches especially giddy comic heights,” while Bloomberg News called it “uproariously alive with guffaws and a barrage of sidesplitters.” Since it closed on Broadway, there have been 498 productions of it in Australia, Canada, China, Romania, Russia, and Sri Lanka, and 48 states in the US—including one at Yale in 2009.

Twain tells us that Tom Driscoll, the spoiled and petted child of privilege who grows up to be a thief and murderer in The Tragedy of Pudd’nhead Wilson (1894), also went to Yale. When Tom was nineteen, “he was sent to Yale. He went handsomely equipped with ‘conditions,’ but otherwise he was not an object of distinction there. He remained at Yale two years, and then threw up the struggle. He came home with his manners a good deal improved; he had lost his surliness and brusqueness, and was rather pleasantly soft and smooth, now; he was furtively, and sometimes openly, ironical of speech. . . . Tom’s Eastern polish was not popular among the young people. They could have endured it, perhaps, if Tom had stopped there; but he wore gloves, and that they couldn’t stand.”

Twain attended a Yale-Princeton football game in 1900, the first college football game he had ever seen. As Yale resoundingly beat Princeton, Twain told a reporter, “Those Yale men must be made of granite, like the rocks of Connecticut!” and added, “those young Elis are too beefy and brawny for the Tigers!” He added that “the country is safe when its young men show such pluck and determination as are here in evidence today.”

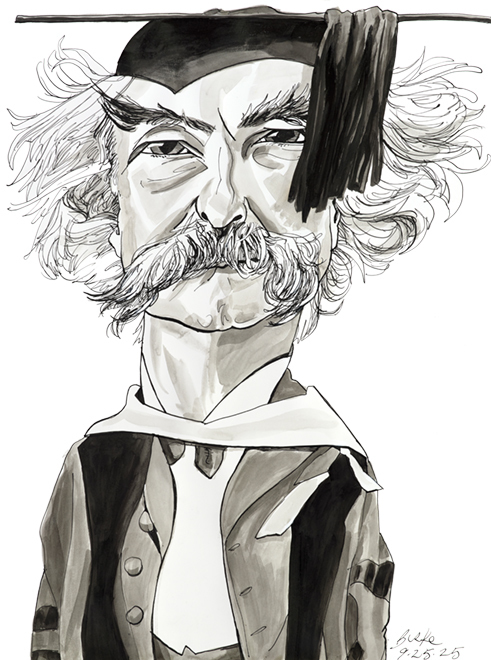

By 1901, the year of Yale’s bicentennial, Twain had become vice president of the Anti-Imperialist league and was a fierce critic of his country’s foreign policy, particularly its unconscionable behavior in the Philippines. His scathing critique of imperialism, “To the Person Sitting in Darkness,” appeared in the North American Review in February of that year and sparked a barrage of hate mail. On October 15, Twichell informed Twain that he would be awarded an honorary doctor of humane letters from Yale. It was “the highest possible compliment,” Twichell said, “for the reason that it will be tendered you by a Corporation of gentlemen the majority of whom do not at-all agree with the views on important questions which you have lately promulgated in speech and in writing and with which you are identified in the public mind.” (Twichell was referring to Twain’s attacks on imperialism.) The members of the Yale Corporation, Twichell continued, “grant, of course, your right to hold and to express those views, though for themselves, they don’t like ’em.”

Resplendent in his new Yale gown, Twain participated in the elaborate bicentennial pageantry alongside his fellow honorees. The illustrious group included a man who mere weeks before had ascended to the presidency: Theodore Roosevelt, whose gung-ho support of an imperialist foreign policy Twain abhorred. Although Roosevelt had enjoyed some of Twain’s books, political stances Twain had taken of late led Roosevelt to call him (privately) a “prize idiot” (and, reportedly, to mutter under his breath that Twain ought to be skinned alive). Twain, in turn, would later call Roosevelt “a showy charlatan,” “the most formidable disaster that has befallen the country since the Civil War,” and “the Tom Sawyer of the political world of the twentieth century, always showing off; always hunting for a chance to show off.” But Twain would write those barbs in autobiographical dictations that were not to be published until a century after Twain’s death.

What Twain preferred to remember from the bicentennial was the pleasure he took in something that had occurred the day before. After a pleasant campus tour, “a great crowd of students thundered the Yale cry, closing with ‘M-a-r-k T-w-a-i-n—Mark Twain!’ & I took off my hat & bowed.” Now that was something to write home about. And he did.

loading

loading

7 comments

-

Tom Miller, 9:29am November 05 2025 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

John Kasson, 12:12pm November 05 2025 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Daniel L. Brinkman, 12:23pm November 05 2025 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Lise Pearlman, 4:40pm November 05 2025 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

David McCarthy '67, 7:13pm November 09 2025 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Susan Boyd-Bowman, 4:30am November 14 2025 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Alan Kitty, 11:45am November 19 2025 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.A delightful read and moving to learn of Twain’s support of African American law student Warner McGuinn, who went on to be a mentor to Thurgood Marshall. How special it must have been to hang out with Twain at Scroll & Key and his shipboard “trial”.

Such a spritely and informative piece by such a learned and inestimable scholar!

In her chapter entitled “(Pseudo-) Scientific Humor” in the 1992 edited volume “American Literature and Science”, Judith Yaross Lee discusses how Twain twice satirized Othniel Charles Marsh, Yale’s acclaimed 19th century Professor of Paleontology. Twain was familiar enough with the four Yale College Scientific Expeditions to the American West led by Marsh in the early 1870s, that he first satirized Marsh in his 1875 “Some Learned Fables for Good Old Boys and Girls” and then again in his 1906 “A Horse’s Tale.” The character Professor Bull Frog in “Learned Fables” was Twain’s caricature of Marsh. Moreover, in his 1864 “A Full and Reliable Account of the Extraordinary Meteoric Shower of Last Saturday Night,” Twain lampoons another 19th century Yale scientist, Benjamin Silliman, Jr., and the "American Journal of Science" which is still published at Yale.

Very enjoyable read with great insights derived from meticulous research. Kudos to my classmate Prof. Shelley Fisher Fishkin for bringing to light long unseen writings of Clemens including a play that delighted modern audiences and even more kudos for publicizing his key role in sponsoring Thurgood Marshall’s mentor. Lise Pearlman

Yale ‘71

A brief comment on a wonderful article. Despite his apparent disdain for comets, Mark Twain was born two weeks after the perihelion (closest approach to the sun) of Halley's Comet in 1835 and died one day after it's next return in 1910. In fact he predicted this in 1909: "The Almighty has said, no doubt, 'Now there are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together."

A wonderful and insightful article by '71 classmate Shelley Fisher Fishkin.

Twain would be proud that the foremost scholar of his work runs an on-line zoomba group and promotes Focus for Democracy!

I have been connected to Twain since Tom Sawyer inspired my first attempted escape from a home life that mirrored the small-town existence of Sam Clemens. Mark Twain Society of Florida is presenting a lecture series and season of themed shows influenced bu the life and work of Mark Twain. This article may become inspiration to some aspects of our improvised material. Thanks1