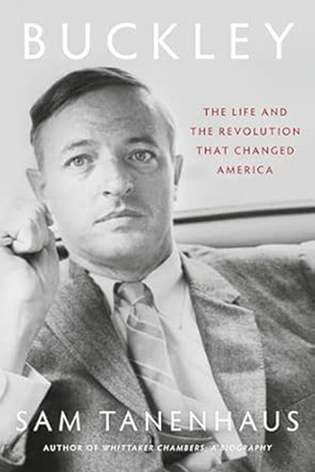

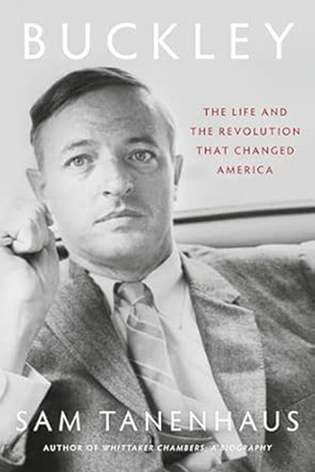

Buckley: The Life and the Revolution that Changed America

Sam Tanenhaus ’78MA

Random House, $40

Reviewed by David Greenberg ’90

In 1997, Sam Tanenhaus published a lauded biography of Whittaker Chambers, the eccentric conservative who in 1948 famously exposed Alger Hiss’s espionage for the Soviet Union. Now arrives Tanenhaus’s long-anticipated sequel of sorts, a lucid, engaging life of William F. Buckley Jr. ’50—probably the most influential journalist in shaping the postwar political right. Possessed of a foppish demeanor, a theatrical transatlantic accent, and an instinct for newsmaking, Buckley burst on the scene with his 1951 polemic God and Man at Yale and, in 1955, by founding National Review, which for decades reigned as the flagship of the conservative movement.

He died in 2008, at 82, before his brand of conservatism gave way to today’s Trumpism.

Tanenhaus digs deeply into Buckley’s early years, including at Yale when he led the Daily News and joined the Political Union and Skull and Bones. He shows Buckley’s youthful politics to have been thoroughly—and, given his later persona, surprisingly—reactionary. Raised in wealth in Connecticut (as well as abroad), Buckley was a Catholic among WASPs, an antiwar America Firster among internationalists, and an apostle of what historians call “paleoconservatism.” Tanenhaus details Buckley’s closeness to Senator Joe McCarthy and spotlights overt racism that appeared in National Review in the 1950s.

For all his importance, Tanenhaus maintains, Buckley was never a systematic “theorist or philosopher” but a provocateur, debater, “publicist and advocate.” Though he authored dozens of books, he never finished a long-contemplated philosophical opus. A master of the syndicated column and the television debate, Buckley won fame as much for hosting Firing Line and dispensing witticisms as for championing pet issues. The book’s other key takeaway, left largely implicit, is that even as Buckley was mainstreaming conservative ideas, he also tugged conservative positions into line with the mainstream. In the 1960s, he broke with the extremist John Birch Society and in the 1990s called out onetime allies like Pat Buchanan and the Holocaust denier Joe Sobran for anti-Semitism. As for opposing the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Buckley admitted years later, “I was wrong.” Today, Buckley protégés from George Will to Mona Charen to his son Christopher rank among the leading conservative voices criticizing the reactionary politics of Donald Trump.

David Greenberg ’90, a historian at Rutgers University, is author, most recently, of John Lewis: A Life.

_________________________________________________________________

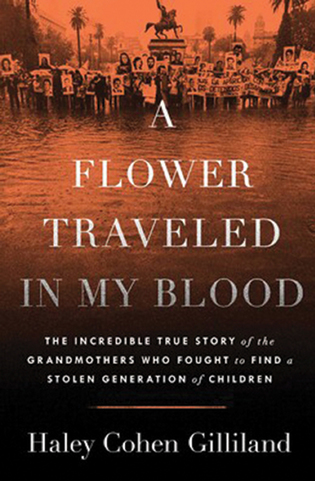

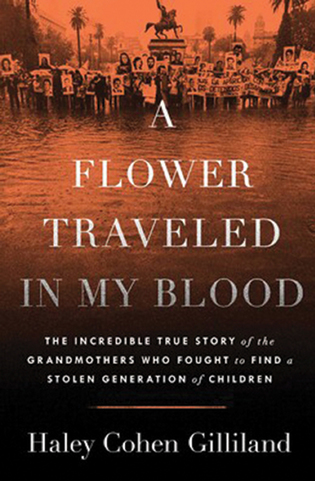

A Flower Traveled in my Blood: The Incredible True Story of the Grandmothers Who Fought to Find a Stolen Generation of Children

Haley Cohen Gilliland ’11

Simon & Schuster, $30

Reviewed by Barbara Demick ’79

On a rainy October afternoon in 1978, intruders stormed a toy and party supply store in a Buenos Aires suburb and punched the owner, José Manuel Pérez Rojo, into submission, clamped handcuffs on him and bundled him into a truck. The abductors sped off to Pérez Rojo’s apartment, where the men grabbed his pregnant partner, Patricia Roisinblit, along with their 15-month-old daughter, Mariana.

So begins A Flower Traveled in My Blood, a compulsively readable whodunit that offers so much more. Cohen Gilliland, director of the Yale Journalism Initiative, takes readers on a deep dive into the brutal politics of late-twentieth-century South America. Like many young intellectuals, José and Patricia had been swept up in the leftist resistance to the military dictatorship that ruled Argentina. Human rights groups estimated that up to 30,000 Argentines were kidnapped, tortured, pushed from airplanes, and otherwise “disappeared” from 1976 to 1983. Cohen Gilliland’s elegantly written and meticulously reported book focuses on the relatives left behind.

Mariana, the toddler, was released by her parents’ kidnappers and raised by relatives. Guillermo, the baby delivered in a military prison, shortly before Patricia was killed, was given for adoption by a military intelligence officer and didn’t learn his true identity until he turned 21. The most compelling figure is the Jewish grandmother, Rosa Tarlovsky de Roisinblit, who helped start a group known as Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo—known as the “Abuelas”—to look for the children and grandchildren taken away by the regime. Cohen Gilliland writes with nuance about the plight of the adopted children torn between the parents who raised them and their genetic kin. This is the very best kind of nonfiction—a narrative the reader can enjoy like a novel while emerging far better educated.

Barbara Demick ’79 is author, most recently, of Daughters of the Bamboo Grove.

_________________________________________________________________

Katabasis

R. F. Kuang ’27PhD

Harper Voyager, $32

Reviewed by Christina Baker Kline ’86

R. F. Kuang’s Katabasis—part fantasy, part allegory, part moral inquiry into the seductions and punishments of knowledge—is a work of genuine intellectual daring. Recasting the mythic descent into the Underworld as an academic trial, Kuang imagines a universe in which scholarship itself becomes a metaphysical ordeal.

Her protagonist, Alice Law, a gifted student at Cambridge in the 1980s, commits an act of catastrophic hubris: A spell gone wrong destroys her mentor and derails her future. To salvage her academic career and her conscience, she must descend through the Eight Courts of Hell, sacrificing half her remaining lifespan in the process.

Kuang’s underworld is rigorous and imaginative, built from paradoxical logic, spectral libraries, and chambers of suffering, calibrated to questions of merit and pain. This inferno is a distorted reflection of the university, with its disputations and hierarchies raised to cosmic stakes. Each court enacts an intellectual sin: greed, pride, wrath. Moving through it all is Alice: shrewd, blinkered, and compelling in her need to find a reckoning she can live with.

If Kuang’s earlier novel Babel explored the moral hubris of empire, Katabasis turns inward—toward the scholar’s compact with ambition, envy, guilt, and the longing to transcend ordinary life through intellect. The novel occasionally courts excess, but Kuang is in full command of her material. A doctoral student at Yale, she writes from inside the world she anatomizes. Katabasis is a supple allegory of academic striving in which the pursuit of truth edges close to self-immolation. Beneath its cerebral scaffolding runs a sly current of humor, a recognition that Hell might look a lot like office hours that never end.

Christina Baker Kline ’86 is author of the forthcoming novel The Foursome, due out this spring.

loading

loading