loading

loading

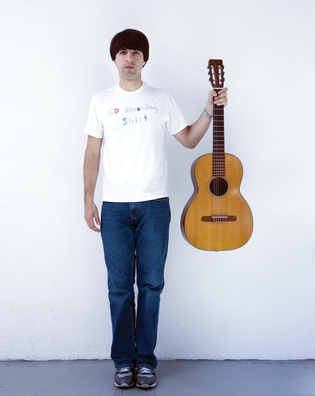

Arts & CultureFunny businessLearning the ropes as a comedian. Anthony Weiss '02 is a staff writer at the Forward.  Comedy CentralWith help from his guitar (and sometimes his grandmothers), Demetri Martin '95 is ascending the ranks of TV comedians. View full imageIn July 1997, Demetri Martin ’95 went onstage for his first stand-up gig. He had written 12 jokes and was hoping for one good laugh. He got six. "I was thrilled," he recalls. "I left the stage thinking, 'Oh man, I'm a comedian.'" At his internship at the Daily Show the next morning, everybody asked how his set went. "And I said, 'Actually, it went well. I got laughs, I had a good set.' They were like, 'Great, great.'" That night, he went onstage again. "Now I'm confident. I get on stage, do the same set. Silence. Bombed, just died. I was shocked. I leave the stage, sweating, thinking, What happened? "The next day I get back to the Daily Show and they say, 'How'd it go?' I say, 'I bombed.' And they said, 'Now you're a comedian.'" Ten years later, Martin is a rising star. He appears frequently on the Daily Show as their "youth correspondent"; he wrote and starred in a web campaign for Microsoft's new Vista operating system; he's writing movie scripts for two major studios (Sony and DreamWorks); and later this year, his sketch-variety television show, Important Things with Demetri Martin, will debut on Comedy Central. Martin is consistently hilarious. A good Demetri Martin joke is a miniature lab experiment with reality, delivered with economy and impeccable timing: "There's a store in my neighborhood called Futon World. I love that name, Futon World. It makes me think of a magical place that becomes less comfortable over time." "A drunk driver is dangerous, but so is a drunk backseat driver - if he's persuasive." "Every dance move is the Robot if you can imagine an advanced enough robot." Martin says that when he goes onstage, he's never certain which jokes will get laughs. "The whole thing is probabilistic. If you tour, and you've done a joke a bunch of times, you get a sense: Oh, this joke works 80 percent of the time, this works 90 percent, this works 50 percent. It's the uncertainty - it's like quantum physics. In a sense." Martin grew up in New Jersey. His middle-class Greek family owned a diner; his father (now deceased) was a Greek Orthodox priest, his mother a nutritionist. He expected to become a corporate lawyer - a big leap for his family - and went straight from Yale to NYU Law School on a scholarship. But he found law school boring. "I was skateboarding a lot, I was skipping classes, I started drawing and painting - stuff I never really did." Instead of studying for finals, he found himself "writing fart jokes." After two years, over the objections of his family, he left school and took temp jobs so he could focus on comedy. As his act developed, he started experimenting: he learned guitar and began playing onstage, and he added a segment with drawings on a large notepad. In five appearances on Last Call with Carson Daly, he has screened gags on an overhead projector, prerecorded his jokes on a cassette player, and brought his grandmothers onstage to tell jokes for him - but he has opened his mouth only once. Now Martin is an established figure, verging on celebrity. Unusually for a comedian, he's even becoming a sex symbol. He looks much younger than his 34 years, with a lanky frame, a pleasant, boyish face, and a brown mop-top hairdo. At his shows, enraptured female fans scream out their love. Several enthusiastic followers have proposed marriage via the Internet. But success doesn't seem to have gone to his head. He says he's still learning. "Woody Allen said, 'The audience teaches you how you're funny.' And it's true. If you pay attention, they guide you. They shape the thing that you're making. It always keeps you down to earth, because if you think you're cool, you're really funny, all you gotta do is bomb."

The comment period has expired.

|

|