loading

loading

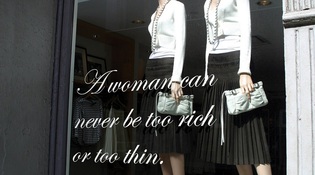

Arts & CultureYou can quote themYou can't be too rich or too thin. Yale law librarian Fred R. Shapiro is the editor of the Yale Book of Quotations.  Photo Illustration: John Paul ChirdonView full imageIn the Yale Book of Quotations, I sought to bring a new kind of research to the quotations field by questioning all received wisdom about the origins of quotations. I have tried to get to the bottom of the years of quoting and requoting, attributing and misattributing, by making use of state-of-the-art online resources and extensive networks of researchers around the world. This enterprise did not stop with the publication of the book. Every week brings new discoveries and information from readers. Below, and in the next few installments of this column, I present some of the post-publication revelations.

Recently, further searching yielded a 1969 Los Angeles Times article quoting socialite Babe Paley: "A woman can never be too rich or too thin." (Babe's father was Yale professor Harvey Cushing, Class of 1891, the pioneer of neurosurgery.) Paley thus takes priority over the duchess as a possible coiner. But an older article, published October 15, 1967, in the Chicago Tribune, puts both attributions in doubt - though it provides no alternative: "'A woman can never be too rich or too thin,' said one of the Beautiful People as reported by Suzy Knickerbocker last spring." Knickerbocker (pseudonym of Aileen Mehle) was a columnist for the New York Daily News; I have not so far found her original column.

But I have now found a usage in the Charleston (West Virginia) Daily Mail of October 26, 1929 - too early for The Door to be the model. And a comic novel of 1922 suggests the phrase was already a cliche, and a joke, by then. In Jiminy, a Gothic spoof by Gilbert Wolf Gabriel, the title character and her husband write their landlord to ask about the decor of a cottage. He replies that a former employee handled it. "'He knows nothing -,' gasped Jiminy," and her husband says, "His ex-butler did it!"

Now, however, etymologist Barry Popik has found new information. On the listserv of the American Dialect Society, Popik explained: "It appears that 'it was a dark and stormy night in winter' was the standard start to a story in the 1820s. . . . The oft-reprinted Dutch short tale, 'Jan Schalken's Three Wishes,' dates before 1830 and seems to have popularized 'dark and stormy night.'" The earliest use Popik located was a story in the Saturday Magazine, June 20, 1822.

The comment period has expired.

|

|