loading

loading

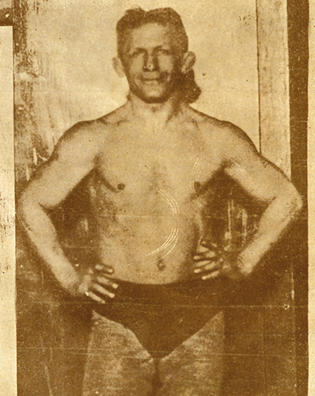

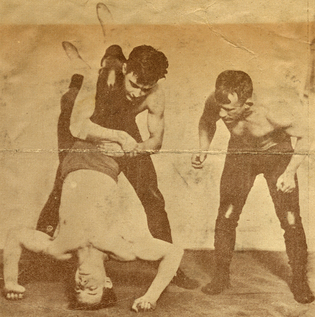

Old YaleThe original celebrity trainerIzzy Winters: wrestler, Yale coach, and celebrated fitness guru. Judith Ann Schiff is chief research archivist at the Yale University Library.  Manuscripts & ArchivesIn an unidentified clipping in Yale’s archives, Winters strikes his own pose. View full imageIn March 1932, Izzy Winters, previously a celebrated wrestling coach at Yale, was featured in the New Yorker in a long article titled simply “Exercise.” The piece described his elite fitness business in New York’s Hotel Roosevelt, where, as the writer put it, “Izzy, a strange man amid strange machinery,… wrings from jaded metropolitan carcasses the metropolitan equivalent of honest sweat.” Winters came early to a profession that is now widespread, that of celebrity trainer. His health and exercise “institutes” in New York and in New Haven (one in West Haven, one in the Taft Hotel) predated even Jack LaLanne’s. His celebrity clients included the boxers Gene Tunney and Jack Dempsey, as well as entertainers Al Jolson, Eddie Cantor, Lanny Ross ’28, and Rudy Vallee ’27. Biographers of William Howard Taft ’78 credit “Professor” Izzy Winters with substantially reducing Taft’s weight through strict diet and regulated exercise. Isadore Louis Winters, born in 1886, was a Jewish immigrant from Austria who grew up in New Haven. Winters left school at the age of 14; not long afterward, in 1902, he achieved national prominence by winning the US lightweight wrestling championship. He then toured America with a burlesque troupe of exhibition wrestlers, including the pioneering female champion Cora Livingston. Three years after the first intercollegiate wrestling dual meet took place—between Yale and Columbia, in 1903—Winters was hired to coach the Yale team. He continued to wrestle professionally, completing 600 bouts in all, even as he trained 19 championship teams of Yale grapplers. (One of those winning teams was captained by his own nephew, Hy Winters ’25S.) Winters believed that getting a team in condition was even more important than teaching the fundamentals of the game. “When I’m judging a coach,” he said, “I look at the bench to see how many of his players are crippled. That shows whether he’s doing a good job.”  Manuscripts & ArchivesIzzy Winters coaches two Yale wrestlers, evidently posing for the camera in this 1925 Yale Daily News clipping. View full imageWinters took time off during World War I to serve at the Pelham Bay Navy Training Station, for nominal pay, teaching sailors and marines jujitsu. In 1921 he joined Yale president James Rowland Angell’s program for Yale’s well-known athletes and coaches to train community leaders, with the goal, according to theNew York Times, of making New Haven “a great centre of athletics and recreational work for all classes.” The faculty of New Haven’s “School of Coaching” included Winters, football legend Walter Camp ’80, Charles Taft ’18 (son of President Taft), and boxing coach Mose King. In 1945 a Utica Daily Presscolumnist, recalling Yale in the 1920s, described “Izzy Winters in his red Stutz racer” as a familiar figure in town. Winters was also a great horse fancier and trainer. (He named one of his champion horses “Sonny Boy,” after Al Jolson’s signature song.) But his principal interest was his New Life Health Farm and the institutes, and in 1926 he resigned from Yale to turn his full attention to physical training. Thirty years later the Bridgeport Sunday Herald would note, “This Is Your Life has been extremely interested in doing a show on Izzy Winters, former Yale wrestling coach and present health farm operator. It would certainly make a tremendously absorbing teevee narrative because Izzy has built up an army of young bodies in his time and bodies that haven’t been so young.” Through the 1950s Winters was featured in many newspaper and magazine photo spreads, proudly displaying his muscular torso and weightlifting strength. He often spoke on television and radio on the importance of maintaining fitness throughout life, asking rhetorically, “Does it do any good to be the richest man in the cemetery?” Winters, who never married, died in 1979 at the age of 93.

The comment period has expired.

|

|