loading

loading

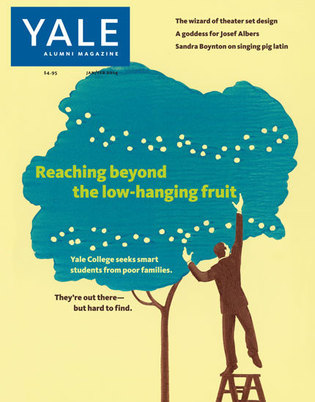

Letters to the EditorAdmissions—and about that cover… View full imageDavid Zax’s article on Yale’s efforts to address the disproportionate representation of wealth and privilege among its student body (“Wanted: Smart Students from Poor Families,” January/February) was thoughtful and interesting. I imagine (and hope), though, that I’m not the only reader you’ll hear from who cringed at the headline on the cover. However nuanced the issues the cover text was trying to distill, the headline “Smart students from poor families. They’re out there—but hard to find” can only be read to suggest smart poor students are scarce. That this headline made it to print without anyone recognizing its offensiveness, let alone its poor characterization of the article, is a bewildering editorial oversight. Sara Cohen ’93

I can’t imagine that the editors of the January/February magazine could possibly have understood how offensive the cover of this issue is, or surely it would not have been printed that way. That an elite institution like Yale could claim that it is hard to find smart people among the poor is appalling. After reading the article, I understand that Yale’s position is much more nuanced than that, but it still does not excuse this cover. The reference to “low-hanging fruit” is disturbing. People are not objects, not fruit, and this term is better suited to ticking items off a list in the order of ease to achieve. Rev. Elaine Ellis Thomas ’13MDiv We struggled with how to communicate the ideas in this article in a compelling way on our cover, and judging by some of the reactions we received, we missed the mark. We should say, in response to the letters above and some other comments we received, that we weren’t comparing low-income students per se to fruit. We were applying the metaphor to all smart students—the low-hanging fruit being the well-off, many of whom apply to Yale and other elite colleges as a matter of course; and the hard-to-reach being the low-income, who, as the article explains, are less prone to think of the likes of Yale when they make their plans for the future.As for poor, smart kids being “hard to find”: we weren’t commenting on the numbers of smart kids who are poor—but rather on the fact that Yale has to work harder to find and recruit low-income students, since they’re unlikely to seek out Yale themselves. Clearly, we should have communicated that idea more fully.And finally, please don’t blame Yale. The magazine is a separate 501(c)3 nonprofit, not run by the university. Our mistakes are our own.—Eds.

Since the late 1990s, I’ve conducted interviews for the Alumni Schools Committee, covering about 13,000 square miles of south-central Colorado. With many candidates lacking adequate transportation or winter driving skills, I’ve had plenty of windshield time to contemplate the many issues associated with recruiting from lower- and middle-class populations in the rural West. Bottom line: there aren’t enough solid candidates to warrant an individual college instituting an admissions department outreach program. What we do have, though, is a great population of motivated students who have no idea that they exemplify “socioeconomic diversity,” who are equally ignorant of the tremendous financial aid available from many of our top schools, and who are systematically fed a short list of state school options by provincial school guidance counselors. An initiative that would bear more fruit for both rural youth and American higher education would be for a consortium of top colleges to join together in something more than the zero-sum game described in the article. An admissions “league” could distribute general material on the merits and true costs of education at member institutions; educate counselors, teachers, and students alike regarding the range of options available and how to evaluate them; and provide reality-based guidance on where a prospective student might best expend her application energy. Greg Felt ’89

As a student coming from an Asian ethnicity, I knew I belonged at Yale because I was smart, and I assumed that other students were there for the same reason. When you lower the bar or your expectations for any reason, other people begin to doubt the merit or worthiness of your being there, whether it is at work, in a school, or even on a team. (“He/she’s a legacy, got connections, plays football/basketball and the team needs a star player.”) So, instead of working together and valuing each individual for the strengths they bring to the class, the students question whether their fellow students even belong in the entering class. Thus “diversity” creates division. Karen C. Lewis ’88

As a would-be progressive, I find most of what passes for progress in the contemporary world questionable at best and horrifying at worst. I am therefore delighted to express my approval of Yale’s decision to reach out to the poor—and to the unfashionable rural poor at that. A young swineherd at Yale does not merely contribute to social justice, but he also offers a perspective on contemporary issues that needs to heard. Philip E. Devine ’66

I read the recent cover story with great interest. I was one of those students long ago in the mid-1970s, from Seattle. I attended one of the lowest-performing high schools in the city. The local story was that the last student to attend an East Coast school from our high school had been 20-plus years before (and he had gone to Harvard!), so it was a Big Deal when I got my acceptance letter. My family, always in the lower economic range, had been on welfare during my junior year in high school and I think was still receiving food stamps or other assistance during my senior year in high school. I know that I was asked to contribute about $3,000 per year to my education (including jobs and loans), and I had a bursar’s job during each of my four years as a Yale undergrad. Thanks to my time at Yale and the resulting degree, doors and relationships have opened up for me which would have been unthinkable otherwise. I am glad to hear that Yale is attempting to make a more organized effort to recruit students like me, and I wish the university well in its efforts! I can vouch for the importance of sending students or other recruiters to some of the high schools that seem the least likely to provide Yale students. There are always students who need to hear that Yale not only exists but is interested in them. Stephen M. Morris ’80

I was one of those poor, Pell grant–receiving kids. When I arrived, by myself, on Old Campus, all I had with me was a weekend bag. I had shipped a couple of boxes via Greyhound. Kids arriving with families and stuffed cars were like another species to me. Because the bus line temporarily lost my boxes, I had only the clothes in my bag for the first few weeks of school. I was grateful the weather did not take a turn. During this period, I would wash my clothes by hand and hang them in the Wright Hall window to dry. I will never forget that the first official communication I got from Yale (after my acceptance letter) was a notice to stop hanging laundry in the window, as it was “unsightly” and “we” were doing all we could to make Yale presentable for Parents’ Weekend. My immediate response to the letter was that it was elitist, rude, and yet somehow trying to ease me into a more genteel world. I removed my clothes from the window and felt chastised. I wish now that I had had then the temerity to push back, but I didn’t. I never did have a parent visit me on Parents’ Weekend, and it occurs to me that the administration could have treated the issue I presented very differently. Calla C. Jo ’88

My class of 1965 was one of the last to have more members from prep schools than public schools. I myself am a “legacy” admission and prep-school grad. It took me ten years to get through a Yale BA, as I flunked out twice. By the time I actually graduated in 1970, the undergraduate population at Yale had changed dramatically, reflecting much more diversity than when I started. 1970 was an exciting and stimulating time to be at Yale! As the articles mention, the past 50 years have seen a huge growth in the disparity between the affluent and the poor, in the United States as well as in the rest of the developed world. It is encouraging that this is now a concern for Yale. Yale’s admissions policies cannot significantly influence the distribution of wealth and power in the USA, but they are congruent with the values structurally implicit in the policies of broader society. Perhaps there will be a shift away from increasing the concentration of wealth in the hands of the few. I hope so, for the sake of my grandchildren. Marshall Hoke ’65

Requiem for a libraryI was so disappointed to see in your magazine a photo of Seeley Mudd Library being torn down (“A Farewell to Mudd,” January/February). I have been a great admirer of that building since I first arrived as a Yale student in 1983. All of those great old masonry Gothic and Classical buildings on campus made a profound impression on me, and I realized early on in my study of architecture how difficult a task it would be to design modern buildings that had the same solidity, warmth, and endless delightful variety of those traditional buildings. But Roth & Moore’s design of Seeley Mudd Library achieved exactly that—a hard-fought but expertly achieved balance between rational and efficient modern building systems on the one hand; and a warm, tactile, humanistic, classical clarity on the other. It was an achievement similar to many of the buildings of Louis Kahn, and, in my opinion, was equally good. I am sure the library or a portion of it could have been incorporated into the new residential colleges with great effect. I am also sure that had Mudd been closer to central campus and its qualities known by more people, its demolition would have been unthinkable. But its influence will live on, in my mind at least. Michael Wetstone ’87, ’91MArch

Making the gradeThe Boston Globe covered in detail the shockingly high percentage of A’s meted out to Harvard students (see “Grade Expectations,” September/October) and noted that Yale was not far (enough) behind on that metric. It led me to imagine the following exchange. After the Harvard dean had extolled the academic values and rigor of a Harvard education to the incoming freshman class, he pointed to a new undergraduate in the audience and asked: “Young lady, what does an A at Harvard mean?” Caught off guard, the young woman looked up from the game of Angry Birds she had been playing on her smartphone during the speech and said, “I don’t know.” “Wrong!” cried the Harvard dean. “That would be an A-minus.” Jon Payson ’79

The SS Elihu YaleThank you very much for highlighting Liberty Ships (“From the Editor,” January/February). As chairman of Project Liberty Ship, I am always pleased to see our organization referenced by the media. Our mission is to educate people of all ages about the vital role of the wartime American Merchant Marine, Naval Armed Guard, and shipbuilders—three largely unheralded groups that were instrumental in the Allied victory in World War II as well as the sealift for Korea and Vietnam— by presenting living history aboard an authentically restored Liberty Ship, the SS John W. Brown. What makes us unique as a museum ship is that we actually get under way and sail with an all-volunteer staff and crew. Again, thank you for mentioning Project Liberty Ship and the importance of these ships and their crews to the war effort. Joe Coelho ’78MDiv

I very much enjoyed your editorial regarding the SS Elihu Yale. Your last sentence, “It’s history that should be remembered,” struck a chord. The 100th anniversary of the outbreak of World War I will occur in 2014. And there is no better way to remember Yale’s connection to the Great War than to acknowledge and celebrate the Yale undergraduates who pioneered military aviation by forming the First Yale Unit, an “aero” club that became the originating squadron of the US Naval Air Reserve. It was the First Yale Unit which fought in WWI and invented American air power. Twenty-eight young men formed the First Yale Unit, led by Bob Lovett ’18, Trubee Davison ’18, Artemus “Di” Gates ’18, Kenny MacLeish ’18, Al Sturtevant ’16S, and last but certainly not least, David “Crock” Ingalls ’20, who would become the best pilot of them all. Residing right there in New Haven is a wonderful author and even finer fellow by the name of Marc Wortman, who wrote a terrific book about the First Yale Unit entitled The Millionaires’ Unit. It is a brilliantly written book, and it takes you back in time to a campus atmosphere that in so many ways was very different from the Yale we know today and at the same time captures the deep-rooted sense of patriotic duty and camaraderie that those 28 young Yale men shared. Dave Harrington ’78 We’re proud to say that Marc Wortman’s book began life as a feature he wrote for the September/October 2003 issue of the Yale Alumni Magazine. You can read the article at archives.yalealumnimagazine.com/issues/03_09/WWI.html.—Eds.

My father, Wilder D. Baker, led the Yale NROTC program in 1938 and 1939 as a career Navy officer; he said it was the best shore duty he ever had. Upon his promotion to captain, he was assigned North Atlantic Convoy duty, escorting outdated US warships to Great Britain. This was just before we started sending troop ships (the so-called Liberties) over as well, but the duty and dangers were just as real. The first US warship sunk was one of his, the Reuben James. He would have been particularly proud to make sure the SS Elihu Yale served its purpose safely and well! Wilder Baker ’53

After the Liberty Ship, the Maritime Commission produced its successor, the Victory Ship. As you recount, the Elihu Yale was one of more than 2,000 Liberty Ships. Yale had its representative Victory Ship, too. The SS Yale Victory was launched on January 31, 1945, in Richmond, California. After a period of merchant service, she was transferred to the Army as a cargo ship and renamed Sgt. Archer T. Gammon. In 1950, with most other Army ships, she was transferred to the Navy’s new Military Sea Transportation Service, retaining her name as USNS Sgt. Archer T. Gammon (T-AK 243). After service in the Korean War, she was finally broken up in Taiwan in 1973. Paul H. Silverstone ’53

The comment period has expired.

|

|