loading

loading

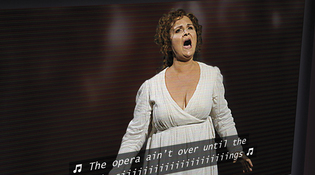

Arts & CultureSayings of the southYou can quote them Yale law librarian Fred R. Shapiro is editor of the Yale Book of Quotations.  John Paul ChirdonView full imageThe opera ain’t overEven in the era before Internet memes, mass media sometimes propagated memorable phrases like wildfire. During the 1978 basketball playoff series between the Washington Bullets and San Antonio Spurs, at a point when the Bullets were ahead three games to one, their coach, Dick Motta, warned against overconfidence: “The opera is not over until the fat lady sings.” Within a matter of weeks, the “fat lady” phrase had become ubiquitous. Motta may have been echoing the well-known Texas sportscaster Dan Cook, and both Motta and Cook have been credited as the originator of the “fat lady” saying. But when I searched the online archive of the Dallas Morning News some years ago for the words “fat lady sings,” up popped a March 10, 1976, sports column using the phrase. And there is another significant 1976 use, in a booklet by Fabia Rue Smith and Charles Rayford Smith entitled Southern Words and Sayings. It includes the adage “Church ain’t out till the fat lady sings.” This citation suggests an origin in Southern folk-speech. And recent research has shown that the “fat lady” has deep roots in Dixie phraseology. The Dictionary of Modern Proverbs (Yale University Press, 2012) lists a variant from The One-Eyed Man, a 1966 novel by Texas-born writer Larry L. King: “Church ain’t over till they sing.” More recently, Garson O’Toole ’86PhD, proprietor of the marvelous website quoteinvestigator.com, has done extensive research on precursors. (“Garson O’Toole” is a pseudonym.) The earliest evidence he found is from the July 12, 1913, issue of the Louisiana Planter and Sugar Manufacturer: “There is an old saying that ‘church is not out till the singing’s done.’” He has found a number of similar locutions recorded in the early and mid-twentieth century, and it is likely that the “fat lady” adage was an embellishment—evoking the image of the buxom Brünnhilde belting out her nearly 20-minute aria at the end of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung. The whole nine yardsThe Southern penchant for linguistic creativity is also evident in “the whole nine yards.” In a prior column (January/February 2013) I announced discoveries by Bonnie Taylor-Blake and myself suggesting that “whole nine yards” was a variation of an earlier formula, “the whole six yards,” which I traced to a Kentucky newspaper in 1912. That finding considerably predated the oldest known use of “whole nine yards” (1956, also in a Kentucky periodical). But just a year later, Taylor-Blake unearthed three early occurrences of “the whole nine yards” in the Mitchell Commercial of southern Indiana: in 1914, 1912—and June 4, 1908. The 1908 use reads, “Roscoe went fishing and has a big story to tell.… He will catch some unsuspecting individual some of these days and give him the whole nine yards.” The same newspaper used “the full nine yards” on May 2, 1907. These findings definitively scotch the popular theories that “whole nine yards” derives from the length of World War II aircraft ammunition belts or from the capacity of concrete trucks. But they don’t prove, yet, that nine yards came before six yards. Taylor-Blake and I believe that the jury is still out on that point, especially since there are many newspapers of the era that have never been digitized. On this question, the fat lady hasn’t sung.

The comment period has expired.

|

|