loading

loading

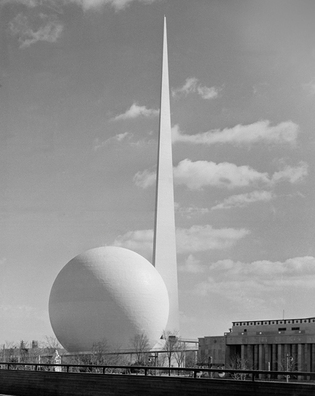

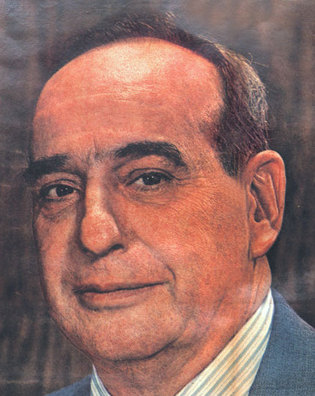

Old YaleRobert Moses and the World’s FairHow the “valley of ashes” became the “World of Tomorrow.” Judith Ann Schiff is chief research archivist at the Yale University Library. Seventy-five years ago, on April 30, 1939, the New York World’s Fair opened. It was the first such exposition to focus on the future—the “World of Tomorrow”—and it featured cutting-edge technologies such as color photography, nylon, air conditioning, electric typewriters, and fluorescent lamps, as well as many innovative buildings.  Associated PressThe fair's two best-known structures, the Perisphere and Trylon. View full imageA number of Yale alumni participated in the fair’s planning and design; some were honored there; and some were inspired to create and contribute to the real “world of tomorrow.” But none had a more significant influence on the planning than New Haven native Robert Moses, Class of 1909. The fair might not have been held in New York at all if its potential value for the city had not captured Moses’s imagination.  Manuscripts and ArchivesRobert Moses, class of 1909, had an enormous influence on the physical environment of New York State. Among his projects was the successful effort to site the 1939 World's Fair in New York City. View full imageRobert Moses’s long career in New York State and City public service would earn him two honorary degrees from Yale. Although he once ran for governor (and lost), his real area of influence was public works. Architecture critic Paul Goldberger ’72 has written that Moses “played a larger role in shaping the physical environment of New York State than any other figure in the twentieth century.” His vision was centered on the automobile and on parklands, and he realized that vision through the numerous public appointments he held throughout his career, including as New York State’s secretary of state and chair of its Council of Parks; New York City’s commissioner of parks; and chair of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority. Among the works Moses built, writes Goldberger, were the Triborough Bridge, Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, West Side Highway, Long Island parkway system, and Lincoln Center. He also created hundreds of playgrounds in New York City and added a vast amount of land to the state’s park system. Moses saw in the World’s Fair an opportunity to transform an eyesore into an idyllic park. This eyesore was an enormous ash dump in Flushing Meadows, in the borough of Queens—memorialized by F. Scott Fitzgerald in The Great Gatsby as the “valley of ashes,” a hellish symbol of the divide between the Long Island rich and the New York City poor. Moses himself wrote, in the Architectural Forum, that “the accumulated clinkers, dust, offscourings, waste, and junk of hundreds of thousands of Brooklyn families had their monument in this horrendous mountain.” He added, “By the greatest stroke of luck, the progenitors of the World’s Fair came along at just this time, and asked me to go into partnership with them in the location of the Fair in the Flushing Meadows. Nothing could have been more opportune.” Moses used this opportunity to have the ash heap cleared—for the fair, but also for the park he had been planning for the site’s future. His plan made the 1939 New York World’s Fair a reality. In later years Moses’s legacy became controversial, because of his preference for highways over mass transit and because neighborhoods were erased when the highways were built. His personality also left its mark. A 1963 CBS report, “The Man Who Built New York,” stated: “For nearly half a century, this man has pushed people around New York. Almost anybody who is anybody has cursed him, fought him, knuckled under to him, and admired him.” After the fair was over, lack of funds prevented Moses from completely realizing all of his plans for Flushing Meadows, but he kept his dream on hold by using the site as the first home of the United Nations. A final opportunity came when he was appointed president of the 1964–65 New York World’s Fair held there. Today the land contains the National Tennis Center and the New York Mets stadium, as well as several 1964 World’s Fair buildings that have been repurposed as museums, a theater, and other amenities. When Moses died in 1981, at the age of 92, Goldberger wrote for the New York Times: “Robert Moses was, in every sense of the word, New York’s master builder.”

The comment period has expired.

|

|