loading

loading

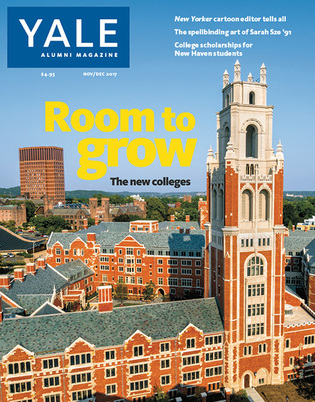

Letters to the EditorLetters: January/February 2018We welcome readers’ letters, which should be mailed to Letters Editor, Yale Alumni Magazine, PO Box 1905, New Haven, CT 06509-1905; e-mailed to [email protected]; or faxed to (203) 432-0651. Due to the volume of correspondence, we are unable to respond to or publish all mail received. Letters accepted for publication are subject to editing.  View full imageCritiquing the collegesWhen Yale’s collegiate gothic buildings were constructed during the early decades of the last century, they represented an attempt to invoke something that was perhaps never truly a part of American university life, and to tie Yale to a decidedly British model, both visually and culturally. James Gamble Rogers’s Branford and Saybrook Colleges are the best examples at Yale, perhaps even in this country. But even then, as the modern movement grew in architecture, the eclecticism of such buildings began to be viewed as an architectural dead end. The new colleges at Yale (“The New College Try,” November/December) look back to an architecture that was itself looking backward. The result is certainly unsatisfying architecturally. If you walk down Chapel Street from quirky Street Hall, past the Old Art Gallery and its assertively modern addition by Louis Kahn, to Paul Rudolph’s Art and Architecture Building and its addition by Gwathmey Siegel, you can see how Yale once undertook to move out of the nineteenth century into the modern world architecturally. Eero Saarinen, in his design for Yale’s previous pair of new colleges, Stiles and Morse, dealt with the same sort of issues that Robert Stern had before him with Murray and Franklin. While some might not consider all of Saarinen’s ideas successful, the design reaches out from Yale’s traditions into new building technology and function in an adventurous way that Stern’s design does not. To me, in every photograph, the new buildings appear clunky, ill-proportioned, and anachronistic, with none of graceful loveliness of Branford and Saybrook. I must hope that today’s students will make something interesting and exciting of their experience with these buildings, because they are certainly here to stay. Peter Conrad ’64, ’68MArch

It was with delight that I read and perused the photographs of Benjamin Franklin and Pauli Murray Colleges. The architectural team from the firm of Robert A. M. Stern (full disclosure: I was friendly with his son as an undergrad at Columbia) is to be commended for their well-researched evocation of the older colleges, without resorting to mere mimicry. Unfortunately, their masterful designs only underscore the opportunity missed in the creation of the new School of Management. Rather than pay tribute in a creative manner to campus tradition, SOM reeks of so many antiseptic, “modern” (read: soon-to-be-dated) office parks and out-of-context architectural-statement pieces. My late father, himself an architect, always stressed the importance of context. Alas, SOMers must still travel to the university’s other quadrangles truly to feel a part of Yale; at least a few more are now a short stroll away. P. J. Lavallée ’06MBA

Former bursary students tell allUnlike Sky Magary ’63, I doubt that work in a Yale dining hall did much toward the development of my character (“Service, Usually with a Smile,” November/December). I do agree with Ed Kamens ’74 on how good it was to work alongside New Haven locals in a dining hall. In my freshman year, 1954–55, I worked as a meat server and assistant dishwasher in the Pierson College dining hall. Mrs. Joyner, supervisor of the dining hall, constantly monitored the size of the portions I served. Occasionally she whispered in my ear, “Donald, you’re serving the boys too much!” But then, when an upperclassman complained about the minuscule portion of meat I allotted him, Mrs. Joyner would loudly reprimand me: “Donald, you’re not serving the boys enough meat!” Then there was the chief dishwasher, Konstantin Lysenko, whom I helped after dinnertime. Konstantin was a displaced person, a short, burly Ukrainian who had been a schoolteacher before World War II. He served as a major in the Soviet Army, was captured by Germans and imprisoned at Dachau, and finally liberated by American troops. Whenever Konstantin caught me lifting trays of unwashed glassware to put them in the industrial dishwashing machine, he muscled me aside to handle the chore himself. He told me that students were “intellectuals” and shouldn’t have to do manual labor. I think, however, that he was really afraid Mrs. Joyner might dismiss him and appoint students to his job if she became aware that one of us could handle it. Later, as an upperclassman, I lived and dined in Pierson College. I was studying intensive Russian by then, and occasionally after dinner Konstantin and I would share a few minutes on a bench in the courtyard, smoking, and he would help me with grammar and pronunciation. It was on that bench one night that we got our first view of Sputnik, the 1957 Soviet satellite, as it flew through space like a slow-moving meteor. It seemed to inspire Konstantin’s long-abused Soviet pride. In a friendly enough tone, as he looked up watching the spacecraft, he said, “We are going to beat you.” I knew him well enough by then not to be offended. Donald Moffitt ’58

Your recent notes about student employment got me to remembering my own experience at Yale in the late 1940s. I was a bursary student, and in my sophomore year I was offered the assignment as assistant to history professor Samuel Flagg Bemis. I met Professor Bemis, and he outlined my work to catalog the books in his library. What a job, and what I learned as I handled all those books! But that was only the beginning. He was at work on a two-volume biography of John Quincy Adams, and there I was to check on references, get needed items from Sterling Library, and proofread his manuscript. Finally, in senior year I took his course in US diplomatic history, an appropriate climax to my undergraduate education. In retrospect, as I look back at my years at Yale, my principal remembrance is my three years working with that wonderful scholar, Samuel Flagg Bemis. Thank you, Yale. Richard Johnson ’49

As a bursary student, I was assigned in my freshman year to wear the white jacket and work in a college dining hall—in my case, Branford College. My duties were working on the serving line and as a bus boy in the dining room, neither job onerous. The pleasure of the job was provided by the folks I dealt with: my fellow bursary students, Bobby the chef, Rita the sweet lady who presided at a desk at the entrance to the dining hall and kept the student attendance, the classy ladies who worked in the dining hall, the upperclassmen who lived in the college, not to mention Norman S. Buck, master of Branford College. In those days, freshmen lived on the Old Campus and had to apply for admittance to a residential college for the next three years. For various reasons, some colleges were considered more desirable than others. (For instance, Silliman and Timothy Dwight appealed to engineering students since they were close to Hillhouse Avenue and Science Hill.) If you worked in the Branford dining hall, you were automatically a “legacy.” Thus I lived the next three years in Branford College. For my sophomore year I was assigned a bursary job in the Audio Visual Center, then located in the basement of Sterling Library. The job consisted primarily in running slide shows and movies for different classes. However, I had gotten a part-time job during the summer at a Texaco station on Whalley Avenue, which paid significantly more than the bursary jobs, so I was granted a “dispensation” and allowed to work there rather than in a university job, which I did till graduation in 1956. Peter H. Tveskov ’56

Climate and the marketSecretary of State John Kerry’s commitment to climate protection (“Climate Confab,” November/December) is much appreciated. However, his faith in a market solution to the problem needs to be questioned. Environmental, social, and ethical criteria are not factored into economic decision making driven by the profit motive. The climate issue and many of the other contemporary environmental and social problems are attributable to unregulated market expansion. The carbon trade put forward by the Paris Climate Agreement and other instruments for climate mitigation turns carbon pollution into a lucrative commodity. The trade in carbon credits encourages the rich countries and companies to pollute more, putting the onus for climate protection on poor countries and their communities. Indigenous and other groups critical of carbon trade and the market approach are urgently calling for a carbon tax and other measures for de-carbonization and corporate regulation. It is well to remember Karl Polanyi’s warning: “To allow the market mechanism to be the sole director of the fate of human beings and the natural environment . . . would result in the demolition of society.” Asoka Bandarage ’80PhD

Mixed message?I was so impressed with Yale’s effort to reduce its carbon footprint, as noted in the article “Putting a Price on Carbon” (November/December), that I clipped it for future reference and pursuit. Kudos to Yale for being proactive in reducing energy consumption and reliance on fossil fuels. Thus, I was quite surprised to view the outside back cover of the same issue and see the full-page ad that promotes ‘‘energy sector” investment. This inconsistency is most disconcerting, and I suggest that the Yale Alumni Magazine walk the walk by staying on the same page in its actions. Leon F. Vinci ’77MPH

Politics and professorsIn your most recent issue, you presented a pie chart that depicts the results of a Yale Daily News survey (“Left and Right at Yale,” November/December) about the personal politics of faculty members. The commentary appears to be an attempt to obfuscate the obvious. That the college professoriate is overwhelmingly liberal is not a “popular perception” that “seems to be true at Yale.” It is a well-established fact, and, I submit, an embarrassing one to boot, given those same colleges’ constant genuflections to critical thinking and independence of mind. In a less hypocritical world, Hillsdale College would not be such a singular and noteworthy exception. Harvey Silverglate’s joke at Harvard’s expense sadly applies to the institution I scarcely recognize as my alma mater: “Harvard’s idea of diversity is for everyone to look different and think alike.” Jim Stiver ’62

Eating at Yale, rememberedMany thanks for an excellent issue regarding Yale and food (September/October). All I can say about your article “Eating at Yale has changed. Drastically” is “You ain’t kidding.” I will confess that as an undergrad, I once participated in a late-night, unauthorized survey of the dining hall of a college that shall not be named. What our impromptu inspection of the kitchen memorably discovered was cases of meat labeled “Grade D—fit for human consumption.” As your article makes clear, Yale has come a long, long way since then. So has New Haven. And so have my eating habits, thanks to my gluten-free vegetarian wife. But no discussion of food at Yale is ever complete without a Proust-like remembrance of those pigs in a blanket and cheeseburgers at the Yankee Doodle. Charles Goodyear ’94

For a Yale graduate student in the fall of 1958 and for those of us in the School of Art and Architecture, eating was a so-so and catch-as-catch-can experience. I arrived with $300 in my checking account. When that ran out, I was saved by a fellow graduate student who got me a job as a busboy at the Law School. It provided all but four meals on the weekend free, in exchange for busing tables in the evening. The meals at the Law School were just fine, but the management was not wonderful at all. In my second year, however, I found much better employment as a waiter at a Law School eating club, Corbey Court, which backed up to the Yale Chaplain’s house. The food was better, and the owner was one of the sweet and generous kind more associated with Yale’s goals of generosity and community. The culinary choices in New Haven for my four weekend meals were limited, compared to what was available when I visited the university in the fall of 2016. There were three restaurants run by George and Harry’s which, though fairly reasonable, still did not fit my limited budget. As for restaurants near the campus, there was the Rathskeller, which was reserved for dates. And there was a coffee shop-cum-restaurant—the name I have forgotten—across the street from Street Hall where the worst 25-cent coffee was available on the site of the Center for British Art. In my second year, a very wonderful girlfriend who lived in the women’s dorm on Temple Street solved my problems and fed me like a king from their small kitchenettes. She had my heart anyway, and her cuisine captured my soul. Konrad Perlman ’60MCP

Kudos for BeckettI am writing in connection with my learning of Tom Beckett’s retiring from his tenure as Yale’s director of athletics (Milestones, November/December). During our 65th, 60th, and 55th Yale reunions, several of my classmates and I attended Tom Beckett’s presentations. We were very impressed with the information he shared with us. Tom Beckett is a true professional. He served Yale superbly. Jim Mourkas ’52

The anthem at The GameWith some 50,000 others, I attended the most recent Harvard-Yale football game in New Haven (“A Football Season to Cheer,” this issue). When it was time for the national anthem, the Harvard team was present, while the Yale team was nowhere to be seen. I assume their lack of presence was their effort at protest. Has no one told them that they represent Yale and not themselves? When you wear the uniform of a team and school, you represent your team and school. The protest was not covered by the New York newspapers. It is another example of an activity that only serves to separate us, not in any way an effort at building a degree of unity or even promoting change or improvement in our society. Yes, there is room for protest, but not at the expense of our respect for our flag or our national symbols. To me, it was an embarrassment and maybe an indication that adult advice and discretion is lacking in my school’s leadership. I would hope that Yale represents much more than I saw on the afternoon of The Game. Monroe E. Haas ’55

Director of Sports Publicity Steve Conn says the team’s absence was not a protest, just a matter of logistics. “The Yale team is always on the field for the anthem unless TV alters our pregame schedule and we don’t want the players standing around too long before the kickoff,” Conn tells us. “We have not been on the field for the anthem for any NBC games in recent years. We have never intentionally avoided the anthem, and we welcome our student-athletes to express themselves in appropriate ways.”—Eds.

Mistaken identityIn the article “Outstanding in the Field” (November/December), your reference to the School of Medicine Physician Associate Program’s two intramural teams incorrectly cited the program as “Physicians Associates.” It is unfortunate that the magazine made this error, especially given that, since its inception in 1970 as one of the earliest PA programs in the country, neither its students nor its graduates have been called Physicians Associates. Barbara Webster ’78PA

The comment period has expired.

|

|