loading

loading

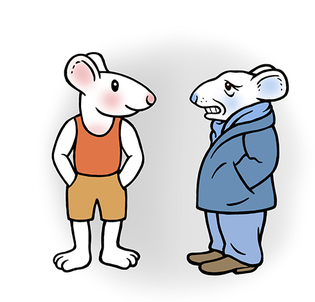

FindingsNoted Gregory NemecView full imageAs we age, humans become more susceptible to cold. Researchers at Yale and the University of California–San Francisco have found a likely cause. Their study shows that the fatty tissue of an aging mouse (and very probably of an aging human) loses its ILC2 cells—immune cells that can restore body temperature despite cold. They also found that stimulating production of new ILC2 cells in aging mice makes them more prone to cold-induced death. But transplanting ILC2 cells from younger mice restores the older animals’ tolerance for cold. The critical takeaway: anyone working to improve the health of the elderly must account for age-related immune-system changes.

Undergraduate Chase Doran Brownstein ’23 went to Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History recently to look at some fossils. It was no ordinary trip: he found new evidence that dinosaurs of the eastern and western US evolved very differently. The specimens Brownstein inspected lived about 85 million years ago, when North America was split into three parts. He examined a herbivorous duck-billed hadrosaur and a carnivorous tyrannosaur—both unearthed in the eastern US—and found they differed in several ways from their counterparts in the West. Dinosaur fossils of the East aren’t often studied, because they’re rare (due to factors from urbanization to ancient glaciers that destroyed fossils). Brownstein’s work is published in Royal Society Open Science.

The comment period has expired.

|

|