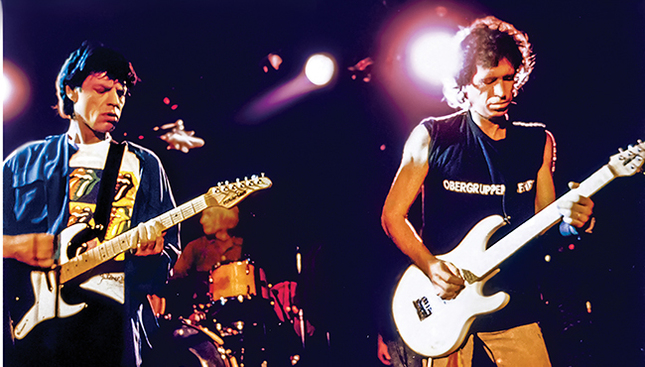

Photograph © Toad’s Place / Brian Phelps

Mick Jagger (left), the late Charlie Watts (center), and Keith Richards onstage at Toad’s Place on August 12, 1989

View full image

Photograph © Toad’s Place / Brian Phelps

Mick Jagger (left), the late Charlie Watts (center), and Keith Richards onstage at Toad’s Place on August 12, 1989

View full image

Toad’s place

The exterior of Toad’s Place in 1989, the year the Rolling Stones made their appearance.

View full image

Toad’s place

The exterior of Toad’s Place in 1989, the year the Rolling Stones made their appearance.

View full image

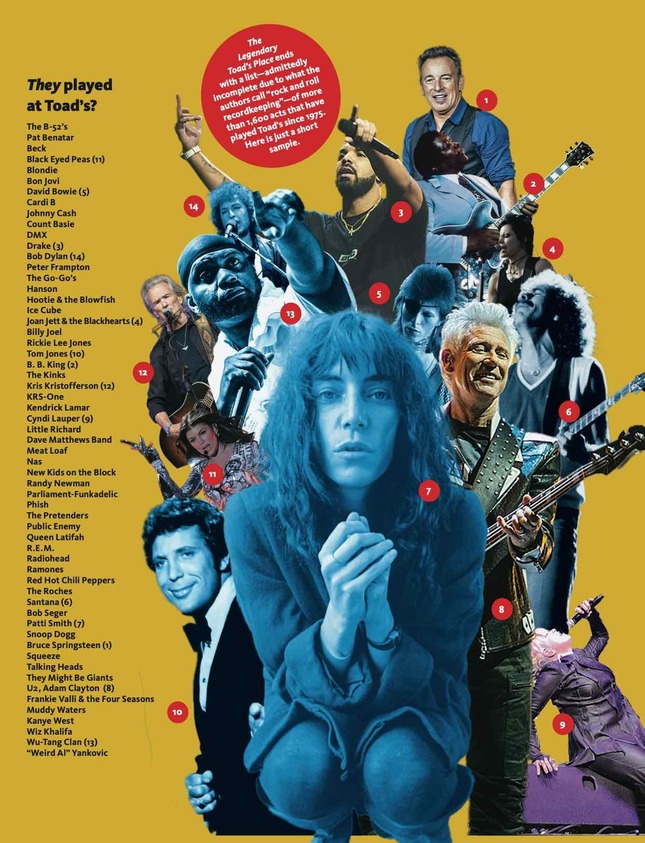

Photos: Wikimedia Commons. Photocollage: Jeanine Dunn.

“The Legendary Toad’s Place” ends with a list--admittedly incomplete due to what the authors call “rock and roll recordkeeping”--of more than 1,600 acts that have played Toad’s since 1975. Click this image for a short sample.

View full image

Photos: Wikimedia Commons. Photocollage: Jeanine Dunn.

“The Legendary Toad’s Place” ends with a list--admittedly incomplete due to what the authors call “rock and roll recordkeeping”--of more than 1,600 acts that have played Toad’s since 1975. Click this image for a short sample.

View full image

For nearly half a century, Toad’s Place on York Street has been a part of the Yale–New Haven social ecosystem, hosting dance parties and showcasing performers on their way up, on their way down, and everywhere in between. Founded by Mike Spoerndle and two partners as a French restaurant in 1975, Toad’s quickly evolved into a music club. It has featured Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, Bob Dylan (in an epic four-hour show), and hundreds more.

In 1976, Brian Phelps started working at Toad’s as manager; he eventually became the club’s owner. In October, Phelps and New Haven journalist Randall Beach published a book, The Legendary Toad’s Place (Globe Pequot, $24.95), full of stories about big nights at the club. The biggest of all took place on August 12, 1989, when the Rolling Stones played a surprise gig before launching their tour. This article, adapted from the book, tells the tale.—The Editors

_______________________________________________________________

In the summer of 1989, the Rolling Stones were preparing to go on tour for the first time in eight years. They had not played in front of a live audience for that entire period, a noteworthy absence for what was still the greatest rock and roll band in the world.

Mick Jagger and Keith Richards had patched up their relationship after some verbal dueling over the merits of their solo albums during the previous years. Along with Charlie Watts, Ronnie Wood, and Bill Wyman, they had gone back into the studio to record Steel Wheels, their 21st studio album. This would turn out to be a comeback for them after the tepid response to their previous effort, Dirty Work, from 1986.

Steel Wheels wouldn’t be released until August 29, 1989, and the first concert of the Stones’ worldwide tour wasn’t scheduled to happen until two days after that, at Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia.

The band needed a quiet, secluded place to rehearse after all those years off the road. Richards, who lived in Connecticut’s Fairfield County (and still does), found a suitable site at the former Wykeham Rise girls’ school in the tiny town of Washington in the northwest hills of Connecticut.

After rehearsing for a few weeks, the Stones, nervous about playing for a live audience after close to a decade of not doing so, started looking for a small club where they could show off their classics, like “Brown Sugar,” and introduce a couple of songs from their new album, including “Mixed Emotions” (which would become a hit after its August 17 release) and “Sad Sad Sad.”

Music promoter Jimmy Koplik got the phone call from the band’s representative on July 28. The question was this: “Where can they play?”

Koplik’s reply: “There’s only one place, and that’s Toad’s.”

Koplik would later explain, “I told them it had to be Toad’s because it was the best club in Connecticut and one of the best in America. Although it had one of the ugliest dressing rooms I had ever seen! And the bathrooms were ugly too. Yet the artists and agents knew it was a great club in which to play, with its fabulous sound system and receptive audience and that Brian [Phelps] and Mike [Spoerndle, then the club’s owner] knew what they were doing.”

Koplik spent six weeks ironing out the details with the band’s people, working carefully to keep the plan a secret. With the show about two weeks off, we met with the Stones’ stage crew. They went through the PA system and lighting to make sure it was up to their needs. We also had to expand the stage.

But still, it wasn’t a sure thing. The band’s people made it clear that if word got out the band was playing at Toad’s and the Stones saw thousands of people on York Street, the bus would just keep on going; there would be no show.

How could we possibly keep this a secret? Could those few people in the know keep quiet about it? Especially big mouth Big Mike?

Koplik remembers being really worried about this. “The problem, I felt, was Mike opening his extremely big mouth,” Koplik said. “He was a very bad person to tell a secret to, as we had learned with the Billy Joel shows. Mike wanted to tell everybody he had the Stones coming in. I told him, ‘If this gets out, it doesn’t happen.’ And so he managed to keep his mouth shut.”

Meanwhile, Koplik had to see to another detail. “I needed to make sure all of the pay phones were disabled so that anybody who came in the door and figured out what was happening couldn’t call a friend and tip them off. There were no cell phones back then, thank God. There’s no way you could pull this off today.”

We put duct tape over all of the Stones’ equipment, which had been brought in earlier that day. We needed to make sure everything that said “Rolling Stones” was covered over.

We also needed a cover story for what was going to happen that night, so we told a few hundred people to “Come down to Toad’s for Jimmy Koplik’s 40th birthday party.” (His birthday was actually August 11, but close enough.)

We billed the night as a dance party, our usual setup for a Saturday night. But before the dancing got going, there would be a band: the Sons of Bob, a group out of North Branford, Connecticut. The admission price to see the Sons of Bob and celebrate Koplik’s birthday was $3.01.

Thank God, Mike managed to stifle himself and not tell people the Stones were coming. But of course there were a few exceptions. Wayne Nuhn, who was a good friend of Mike’s and the head waiter of Mory’s, the Yale-connected dining club next door, recalls what happened on the morning of August 12.

“I missed my trash pickup at my home in North Haven. I just didn’t get it out to the curb in time. But then I realized I could bring my trash to Mory’s, so I drove down there. And I see Mike in front of Toad’s; he’s unloading equipment from a truck. And I’m thinking, Why is Mike doing this? What about the roadies? I walked over and I said, ‘Hi Mike.’ He said, ‘Hi Wayne.’ He had a strange look on his face, like he was hiding something. Then he said, ‘Wayne, I’m going to tell you something I’ve only told my wife and my priest: I’ve got the Rolling Stones coming here tonight.’ I said, ‘Sure, tell me another one.’ But then I saw he was serious.

And he said, ‘Why don’t you bring your wife and your sons down tonight? The Stones go on at 10 o’clock. We’re gonna lock the doors.’ Well, we got down there that night and we were 20 feet from the stage at the center of the room. What a wonderful night! Just think, if it wasn’t for my trash problem, I would’ve missed the Stones!”

We had an incredible number of details to take care of in order to make sure the show went smoothly and in accordance with the Stones’ specifications. One of the key matters I had to oversee was having somebody pick up a bottle of Rebel Yell for Keith Richards at the Quality Wine Shop around the corner. It happened that there was a guy in the store who knew everything about the Stones and had heard the rumor they might be playing at Toad’s. Seeing our bar helper buy that bottle of Rebel Yell was the smoking gun for that fan. He alerted a few of his friends and they saw the show they would never forget.

As incredible as it sounds in retrospect, we were having a problem drawing a good crowd! “I had kept it too quiet,” recalls Koplik. “We had trouble getting people off the street to come inside. It was supposed to be a dance night, and those didn’t start until 11 pm. But the Stones wanted to start playing at about 10:30. At 8:30 or 9 o’clock we only had a couple hundred people, and many of those were record company executives.”

Koplik’s friends were there for the “birthday party,” but some other people had shown up because they had been tipped off about what was really about to happen. Gradually the crowd inside started to build as more people heard the rumor about the Stones and ran down to see if it could possibly be true.

John Griffin, a DJ and program director at the radio station WPLR, remembers seeing two angry young women outside the ladies’ bathroom early that evening. “They were saying, ‘I thought this was supposed to be a dance party! But some band, the Sons of Bob, is playing. We’re getting out of here!’ I could have told them not to leave, but I just figured, ‘No, let them suffer.’”

At 9:15 the Sons of Bob began their six-song, 30-minute set. They were under strict instructions not to play for more than 30 minutes. The crowd gave the band a warm reception; many people in the room had found out by then that the Stones were on deck, so everybody was in a good mood and getting more and more excited.

“Their bus was coming in from that girls’ school in Washington,” Koplik recalls. “When I gave the okay, the bus came right up to the sidewalk near the club. We had security people block off the area, and the Stones came in the side door, going straight downstairs to the dressing room.”

WPLR DJ Mike Lapitino recalls, “I was standing outside the dressing room, and I saw the Stones come in. What struck me was how short they all were, especially Bill Wyman. You think they’re bigger than life.”

Koplik remembers being in that dressing room with the Stones for only about two minutes as they were getting ready to do the show. “Mick wanted me to introduce them,” he said. “But I couldn’t do that to Mike. I said, ‘How about if Mike and I share the announcement?’ Mick said, ‘Okay, as long as you don’t screw it up. You have to say this: ‘Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome the Rolling Stones.’”

Koplik recalls pulling Mike aside and explaining, “Mike, it’s very simple. All you have to say is, ‘Ladies and gentlemen’ and I’ll say the rest.”

At 10:40 pm, Mike and Koplik had one of the biggest moments of their lives. Mike managed to get out his “Ladies and gentlemen,” and Koplik finished with, “Please welcome the Rolling Stones!” And then, unbelievably, there they were! On stage! Right in front of us, the greatest rock ’n’ roll band in the world!

Keith hit the opening riff of “Start Me Up” and the room lit up. “When I heard those guitar lines,” said Koplik, “I thought, Oh my God, they’re really here!”

Jagger, wearing a T-shirt with multiple reproductions of the Rolling Stones logo with the big lips and tongue, was then 46 but had no trouble jumping and prancing just as he had when the band hit it big in 1964. He took his first jump at the outset of “Start Me Up.” Later he called out, “Everybody doin’ alright?” Keith grinned out at the crowd as he traded licks with Wood. These were the intimate details you could never see from way back at a stadium seat.

Although all of the club’s phones were taped down, somehow the word had gotten out. We must have had about 3,000 people on the sidewalk and in the street. They too were going wild. New Haven cops set up barricades and, with the help of our security team, held the crowd back. Eventually we threw open the doors so everybody could at least hear the show.

Earlier that evening I had let in a guy who had Associated Press credentials. This turned out to be a great move, because the AP story and photo made it into almost every newspaper in the country and beyond, including in China. It was like we had hit the biggest lottery that ever existed.

The Stones had decided they would play 11 songs, which would take just under an hour. (They were on stage for 55 minutes.) The lineup went like this: “Start Me Up,” “Bitch,” “Tumbling Dice,” “Sad Sad Sad,” “Miss You,” “Little Red Rooster” (originally by Willie Dixon), “Honky Tonk Women,” “Mixed Emotions,” “It’s Only Rock ’n’ Roll (But I Like It),” “Brown Sugar,” and “Jumpin’ Jack Flash.” There would be no encore. What do you expect for $3.01?

“This is the first time we’re playing this song in public,” Jagger said as he introduced “Mixed Emotions.” “So please be kind.” He appeared anxious about whether those new ones would go over well and was visibly pleased by the crowd’s warm response.

“We’ve been playing for about six weeks ourselves,” Jagger said near the end of the show. “It’s great to get some people to play for, you know.”

When they wrapped it up, basking in the rabid applause, Jagger slapped hands with the people at the edge of the stage. “You’re too kind,” he told them. “My goodness!”

Then the Stones ran downstairs and went back into the dressing room for just a few minutes.

“They invited me in,” said Koplik. “Clearly they were all very pleased with how the show went. They said, ‘We have a birthday present for you’ and handed me a check for $10,000! I split it with Mike.”

The Stones wanted to get going, but they went out the front door, into the teeth of the hyped-up crowd! Why? “Mick likes crowds,” Koplik explains.

“We had to do a human chain to get them to their bus,” remembers security head Tank Dunbar. “There were people banging on the windows, running around the sides.”

When the people who had seen the show started to walk out the door, the people outside were drooling as they watched them, as if they were seeing diners who had been treated to a sumptuous feast. It was like the folks outside were starving, and all they wanted was a crumb by touching one of “the chosen.” And the people who were coming out were yelling and pumping their fists. They still couldn’t believe what they had seen; it was something out of a dream, the show of a lifetime, something only a very few lucky people were able to see. They would have a story they could live on for the rest of their lives.

loading

loading