Yale Center for British Art

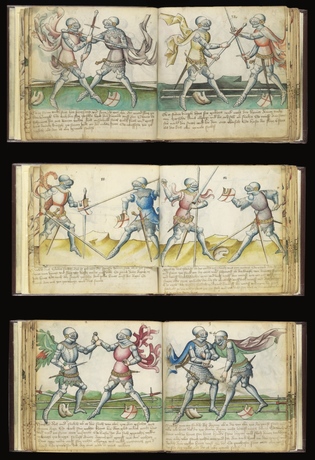

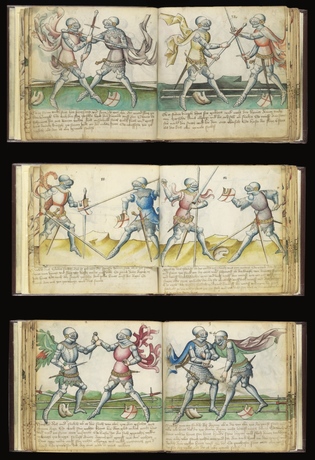

Spreads from the New Haven Gladiatoria, a fifteenth-century fencing manual, show a variety of techniques: holding the sword by the blade and striking the opponent with the cross guard (top left and right), using a spear and sword together (center left), unscrewing the pommel from the sword and throwing it at the opponent (center right), and dueling with daggers (bottom left and right).

View full image

We have all seen sword fights on film, on TV, in games. But what was medieval fencing really like? Over the last two decades, scholars and practitioners have tried to reconstruct late medieval fencing as it was originally practiced. Their main method has been to study surviving fencing manuals from the fourteenth through the sixteenth centuries. These days you can learn the reconstructed art of the sword at many martial arts clubs around the world, including New Haven Historical Fencing. Occasionally, I have reason to bring medieval fencing manuals into my Yale classes, too.

The oldest fencing manual in Yale’s collections, housed at the Center for British Art, is a mid-fifteenth-century manuscript known as the New Haven Gladiatoria. Each page of the Gladiatoria depicts two armored men fighting, with a caption in German that explains the techniques they are using. The men fight with spears, then two-handed longswords, and lastly by wrestling on the ground, daggers in hand. This progression of weapons makes it clear that the manual is teaching techniques for use in a trial by combat—an officially sanctioned duel. The Gladiatoria is gorgeously illustrated and richly colored, and I have no doubt that it once belonged to a German-speaking nobleman who wanted to show off his own chivalric qualities. But I also wonder if it was made as a kind of résumé by a fifteenth-century fencing master in search of a noble patron.

The Gladiatoria includes a few especially intriguing techniques. At one point it advises you to sneakily unscrew the pommel of your longsword, throw it at the other fellow as a distraction, and then run him through with a spear. Here it is fun to try to read the manual’s tone. Is there some comedy here, even in the original? Or is it all deadly serious? This pommel-throwing trick appears so rarely in manuals from the period that it might indeed be just a bit of fun. And yet the standard repertoire of the period, which was used in deadly earnest, does include many techniques that look strange to our eyes. An example: The Gladiatoria illustrates the so-called mordhau (“murder stroke”), in which you grip your two-handed longsword upside-down—by the blade instead of the handle—and then use the pommel as a kind of mace, hoping to ram your protruding cross guard through the vision slot of the other guy’s helmet, thus shoving a bar of steel into his eye. This sounds impractical, but so many manuals of the period include it that one can only assume it was considered a plausible move.

Manuals like this one can be great fun in the classroom: students (like their teachers) tend to find them charismatic and appalling, bewitching and repellent by turns. The manuals are not without a sense of humor, but that sense of humor only sometimes overlaps with ours. The fact that their tone is difficult to interpret makes them a nice puzzle on which to train our sense of historical difference. For example, the men fighting for their honor in the Gladiatoria are presumably meant to be read as quite masculine, but there is much about their style of dress that strikes our eyes otherwise. Yes, they are trying to kill each other with deadly objects while wearing heavy steel armor, but what about their daintily pointed toes? Most conspicuously, the illustrator seems to have taken great joy in providing them with magnificent, brightly colored capes, billowing up all over the page in stylized form. Presumably fifteenth-century readers experienced all this as manly, noble, and deadly, but today it strikes many of us as flamboyant, impractical, camp. Thus the manual offers us a good example of how our aesthetic tastes change over time. In fifteenth-century ruling-class culture, a taste for noble, manly violence and a taste for spectacular, courtly display went hand in hand.

You can learn from these manuals by reading them, but you can learn a lot more by acquiring some swords and practicing the techniques. The manuals can be hard to interpret if you’ve never picked up a sword. For example, the Gladiatoria includes a number of plates in which the two men look as if they are simply dancing together, and many students interpret them that way at first. But when students start to puzzle out the movements in practice, sword in hand, it becomes clear that one of these “dancers” must be in great pain, having been stabbed, sliced, or joint-locked in some way that is not apparent at first glance. Again here, the courtliness and the bloodiness of medieval ruling-class culture go hand in hand. In this case, it is by following the manual’s instructions that we come to understand the violence implicit in what might otherwise seem mere courtly display.

loading

loading

1 comment

-

Jeffrey Townsend, 3:01pm September 11 2025 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.Only a true master can make both billowing cloaks and pommel-throws appear at once scholarly and deadly. Bravo — a feat and a flourish straight from the source.