loading

loading

featuresTrailblazersYale-NUS College is educating some remarkable people. We talked with a few of the first graduates. Caroline Lester ’14 is a freelance writer and contributor to Connecticut Public Radio.  Courtesy Yale NUSProfessor Jeremy Kua is shown here teaching his Scientific Inquiry course to the inaugural class in 2013. (He has since left Yale-NUS.) The college brings liberal arts education to a part of the world where single-track professional training has been the norm. View full image“I graduated and was like, I could be making bank,” says Subhas Nair, who received his BA in 2017 from Yale-NUS College. “But that’s not what I wanted to do. I wanted to inspire people.” Nair, a Singaporean, is a poet and rapper. Yale-NUS has been touted by admirers as a grand experiment in education, a signal of what’s to come with global universities, and a bold attempt to spread the American liberal arts system to the East. The college is a joint project of Yale University and the National University of Singapore. When it was proposed publicly, in 2010, controversy erupted. Critics at Yale and elsewhere charged that Singapore’s tight restrictions on free speech would smother academic freedom, threatening the liberal arts ideal of open discussion. Others feared a dilution of the Yale name, or even an insidious brand of colonialism. For their part, many Singaporeans worried about departing from the single-track professional training widely favored by Asian colleges. Could the school’s liberal arts graduates land jobs? It will take several years before all these questions are answered. But there is finally a yardstick for the new institution’s success: the school’s first two graduating classes. The emerging Yale-NUS alumni are being watched. Closely. Their trajectories may become a metric of just how good this idea is.

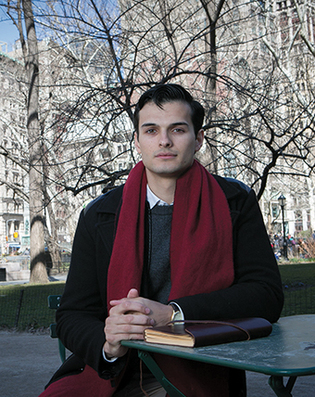

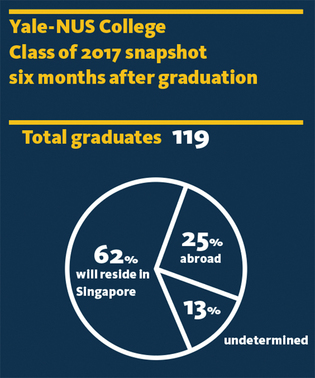

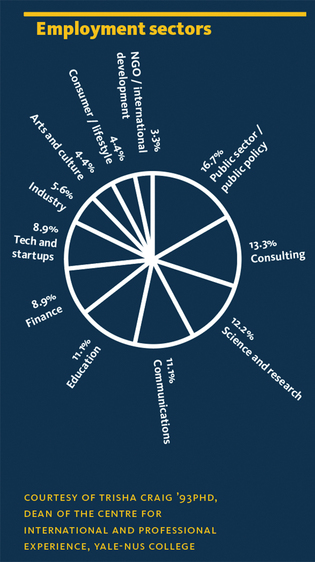

Bob LeeSingaporean poet-rapper Subhas Nair was the first in his family to attend college. His financial aid package at Yale-NUS also allowed him to spend time at Yale and Columbia. View full imageFor Subhas Nair, “college was never the plan,” he recalls; his family couldn’t afford it. But Yale-NUS—and its generous financial aid package—changed everything. In many ways, Nair experienced the best of what Yale-NUS offers its students. He became the first member of his family to attend college. The financial aid allowed him to get an education and to travel overseas; he spent a semester abroad at an Ivy League college and a summer in an internship in Hong Kong. “The fact that I spent a summer immersion program at Yale and a semester at Columbia—I’m punching above my trajectory,” he tells me. Nair, who majored in urban studies, says the liberal arts curriculum pushed him to start questioning systems in his own life. And his music is truly the product of a liberal arts degree. In a single released in the summer of 2017, he references Potemkin cities and includes lyrics like “Meritocracy is a hypocrisy that mainstreams mediocrity.” His upcoming album will be partly about “the conditioning of masculinity,” as well as “inclusivity and what that means for marginalized communities,” but his main theme is justice: with music, he plans to take the Singaporean government to task and challenge others to do the same. It’s a bold mission in a state that in 2016 jailed a 17-year-old vlogger for “wounding the feelings of Muslims and Christians.” Nair’s career choice isn’t typical for Yale-NUS graduates. According to a 2017 Yale-NUS internal survey, the top career field for the graduates of the Class of 2017 was the public sector and policy (17 percent). The runner-up: consulting (14 percent).* A national survey six months after the class graduated showed that a full 93 percent of the class had “post-grad plans”: job offers, acceptance to graduate school, or fellowships. (Part-time jobs were included in the survey; 106 of the 119 graduates of 2017 responded to the survey.) Some Yale-NUS alumni are looking beyond typical professions. One woman is in Spain, training to become a nun. There is a PhD candidate in psychology at Yale and one in astrophysics at Harvard. One graduate is a Schwarzman Scholar, another a Rhodes Scholar. Yale-NUS’s inaugural class has been touted as the best of the best. Back in 2013, the acceptance rate for the nascent college was 4 percent; in the past four years, as the class size has increased, it has risen to 7 percent, a rate comparable to Yale’s. These are very low numbers, especially for a new institution. For acceptance rates like that, a school the size of Yale-NUS has to secure some 8,000 applicants, an almost impossible task for a brand-new college. But the school has a major advantage: anyone submitting an application to Yale can simply check a box and simultaneously apply to Yale-NUS (though test scores and transcripts still need to be submitted). Pericles Lewis, a longtime Yale comparative literature professor, served as the first president of Yale-NUS before returning to Yale last fall as a vice president and deputy provost overseeing international matters. He believes that in some ways, the first Yale-NUS alumni have been “broader than our Yale college students.” The percentages of Yale and Yale-NUS 2017 graduates who went into finance or consulting (according to the internal survey) are similar—27 percent to 24 percent.* Still, Lewis feels that for Yale-NUS students, a lucrative career is “not the driving force in the way it is for certain segments of [Yale’s] undergraduate population.”  Mark OstowJoan Ongchoco, now studying for her PhD in psychology at Yale, says she knew being part of a pioneering class at Yale-NUS would be challenging. She founded four student groups while she was there. View full imageThe first two classes are unique: they chose to attend a school without a track record, or even a campus: it was still under construction when they entered. One Yale-NUS administrator believes their “sense of adventure is not something that will be replicated.” Those first students dove headfirst into an educational experiment, determined to build something out of nothing. They created clubs, a student government, even annual events. “We signed up for this,” says Joan Ongchoco, Class of 2017. “We knew it’d be difficult.” Ongchoco came from a private school in the Philippines. She tells me that, before applying to Yale-NUS, she was on track to study business management. Now, she’s a PhD candidate in psychology at Yale. In her four years at Yale-NUS, Ongchoco founded as many groups: the debate team, the ballroom dance team, another general dance society, and the college bookstore. She remembers long, protracted arguments with the debate team about whom to send to competitions. Would an established club have had the same frictions? She doesn’t think so. But she loved being a pioneer. “Nothing matched the feeling of bringing that first trophy home,” she says.  Julie BrownMembers of the first Yale-NUS class attended a three-week orientation in New Haven for first-years. Australian Raeden Richardson remembers exploring “the great traditions that came before us.” View full image View full image Employment sector data are from a 2017 internal survey. View full image“We have quite an intense ownership of Yale-NUS,” says Raeden Richardson, a 2017 graduate and cofounder of an academic tutoring service in Melbourne, Australia. “If something belittling is said about our school in public, it’s almost as if it’s a criticism of us.” Richardson had never left Australia before his admittance to Yale-NUS. After, in a matter of months, he traveled to both Singapore and the United States, all on his new college’s dime. The summer before freshman year started, Richardson and his classmates were flown, en masse, to New Haven. There they received a three-week freshman orientation that also taught them “about the histories and traditions of Yale.” They were given tours of residential colleges, treated to a series of lectures for Yale’s Grand Strategy class, and visited the Law School. Richardson felt that the purpose of the trip was “revering the great traditions that had come before us.” After their Yale orientation, the class returned to Singapore and their temporary home, an NUS building overlooking the construction site. In their junior year they moved onto their new campus. The land Yale-NUS now occupies was formerly a golf course; the quad undulates. But today, the manicured lawn is interrupted by trees, ferns, and an “Eco-Pond” (nicknamed “Dengue Pond” by the students) that doubles as a filtration system. The three residential colleges—Saga, Elm, and Cendana—are each located in a towering apartment building. Every three or four floors one can see an open “sky garden,” an outside balcony with benches and potted plants. Paths wind between looming, white buildings meticulously designed to merge form, function, and sustainability. Many aspects of Yale-NUS culture are imports from Yale, built into the system before the students arrived—butteries and Rectors’ Teas, for example. Every residential college has the suites, dining hall, and common room that are hallmarks of the Yale residential system. But the Class of 2017 is the only class that visited New Haven as a whole, and Yale-NUS is a stone’s throw from its other parent institution. Students use NUS lab facilities and can petition to take NUS classes; NUS students, in turn, can petition to take most Yale-NUS classes. Their tuition is subsidized by the Singaporean government. “Ultimately,” says Richardson, “what’s in front of you is NUS.” Still, most Yale-NUS faculty come from the United States as well as Singapore; Yale professors sometimes take a semester’s leave to teach at the college. And Yale-NUS’s core curriculum draws from both Eastern and Western sources. Every student will take ten courses that span from Scientific Inquiry to Modern Social Thought. Students might read Hamlet alongside Letters of a Javanese Princess and The Tale of Genji. They learn history and political thought in a global context. Their classmates come from all over the world. The largest group has always been from Singapore; in the Class of 2022, the next largest come from India, the United States, and China. In all, it has students of 45 nationalities.

Daryl Yang spent much of his free time at Yale-NUS lobbying for LGBTQ+ rights. He says the college is a large reason this work has been possible. Singapore criminalizes homosexuality: under current law, it is punishable by up to two years in prison (though the government has said it will not enforce this law). Yang, a Singaporean, came out to his family halfway through his national service. When he heard about The G-Spot, a Yale-NUS student club that describes itself as the college’s gender and sexuality alliance, he felt Yale-NUS represented one of the only places in Singapore where he could “exploit the space to push this [issue] further.” The college has been clear about supporting students promoting LGBTQ+ issues, he says. “The challenge comes from balancing this environment we have within Yale-NUS against the larger Singaporean society’s attitudes.” But he sees the college as a strategic location on which to base his activism. He’s now in his fifth year at the school, in a joint program between Yale-NUS and NUS Law, and he plans to continue his work. “I’ve never been in classrooms with such diverse opinions as Yale-NUS,” says Mollie Saltskog, who graduated in 2017. Saltskog is from Sweden, but she applied exclusively to American colleges. “I was actually very dead set on going to an American school, because I wanted an American liberal arts education,” she says. But when she applied to Yale, she checked the box that sends a Yale application to Yale-NUS as well. Saltskog’s final decision came down to Tufts or Yale-NUS. She moved to Singapore three months later. “The professors teach with a non-American– centered perspective, which I think is incredibly important in the twenty-first century. And I think that prepared me very well for what I’m doing now.” Saltskog is speaking to me from China, where she’s enrolled at Tsinghua University as a Schwarzman Scholar. She says Yale-NUS’s global core curriculum prepared her for a career in international relations. Pericles Lewis believes that, 100 years from now, a truly global university cannot be based solely in New Haven, or solely on the Western canon. Is the Yale-NUS blueprint a better answer? As its students graduate and make their way through their lives and careers, we’ll learn more. _____________________________ * In our print edition and in an earlier version of this online article, we conflated the results of two different surveys of Class of 2017 graduates. We have corrected the mistakes.

The comment period has expired.

|

|